On the evidence of last week's events, business has entered a curious search for higher purpose, while craft is all higher purpose and no utility.

On the evidence of last week's events, business has entered a curious search for higher purpose, while craft is all higher purpose and no utility.

I arrived at the Design Council/Economists Big Rethink design summit on Thursday in time to hear Roberto Verganti's thoughts on radical meaning. We know how to improve things using technology, he said, and everyone knows studying users will help design, but we don't know how to improve meaning. Designers have become much less visionary in the last ten years, according to Verganti, because design has dwelt on processses, methods, tools, brainstorming and ethnography - growing closer in its language to business than to its origins in arts and crafts - none of which teaches you to discover meaning. Successful companies, he argues, get close to "interpreters", not to users.

Who are they, I wonder? Novellists, curators, illustrators, art directors? It's that storytelling imperative again. Two case studies followed; both qutie radical re-interpretations of meaning. Hugo Spowers of the Riversimple transport enterprise spoke about selling "miles travelled as a service, rather than cars as products", and the winsome Californian Jeff Denby told the story of his integrated organic underwear/packaging/charitable giving/social networking enterprise PACT which "put meaning where generally there was no meaning" - i.e. your underwear drawer; true enough.

Deadly presentations about Samsung and Microsoft confirmed that their entire meaning is to chase customers (try rendering the Microsoft logo as flower-petals), and Vijay Vaitheeswaran summed up the morning's insight as " Good design is always human-centred design". It struck me as quite hard to find examples of design that are not human-centred; performed, as it is, by humans for humans. More a question of degree I suppose - Albert Speer and Howard Roark being less "human-centred" than, say, Lord Rogers.

Paul Bennett of the design-thinking mothership IDEO opened the afternoon with a rousing presentation about meaning, underpinned by the creed of co-creation. I liked that his presentation was entirely typographic, but was driven to mean-spirited disdain by his portentous use of the full stop ("We need to reboot our values. Our choices. Our morality. Ourselves.) and the italic ("Managing your expectations". "So what did we learn?"). The ensuing workshops, led by valiant IDEO colleagues, yielded insights in greater volume than quality, I would say. Verganti told me later he thinks that's a feature of "idea-generation" techniques: you get a long list but not necessarily any pearls. My session on EDF Energy contrived a "higher purpose" in the French utility supplier partnering with people to produce energy (see below).

Since day two's Innovation Master Class promised to "leave you with new means to innovate using design", the principal speakers were asked for a final word; a practical tip, as it were. Richard Seymour urged "More anthropology; less technology"; David Kester said "Find new spaces to collaborate" and Bonnie Dean of Quantum Property Partnership's less alluring advice was "Bring design-thinking in early". Paul Bennett had spoken repeatedly of "giving us things to do on Monday" but in the conversion of insight into "tools", "means" and "things to do", I think we've a long way to go.

Using my workshop session as an example, guided by the incisive Andrea Koestenbaum of IDEO, we discussed EDF's Assets and Capabiltiies under the headline Now; the opportunities ahead under Now What?; the higher purpose that answered these opportunities under Higher Purpose; and, well, we didn't really get around to the final section, How? See that's the thing: I work for a think tank so there's no shortage of higher purpose, but it doesn't make the "how?" any easier. And anyway, a healthy skeptic in my group kept reminding us that energy was "just a commodity" and had no higher purpose.

The prevailing wind of participation, user engagement, co-production etc. - and not just in design - has saddled us with a great how? How exactly do you turn what "people" do and say and desire into ideas that have life; how do you make "people" have the ideas themselves? Since we published the thought that design can make everone more resourceful and self-reliant, we're as implicated as anyone in calibrating the answer, and it's not obvious.

I also attended the launch of the Crafts Council campaign Craft Matters. I do think craft matters a lot; certainly the haptic sense of schoolchildren should be nurtured as much as their visual and aural concentration skills, as Rosie Greenlees put it. But I'm always disappointed by the arguments, which all seem to be about supporting potters and weavers. I find myself wanting to elevate craft to a great spectrum of everything from handwriting to plumbing, with potting and weaving somewhere in the recherché middle, in the mode of Richard Sennett but perhaps in more accessible language. I fully concede that anyone making a living from craft needs to be exemplary in flexibility and resourcefulness (although if they're flexible and resourceful I wonder why they need so much support). If you linked the haptic sense of potters and weavers with the haptic sense of heating engineers and carpenters and sign-writers, you'd have a utility argument as well. Flexible, resourceful and occasionally useful - what's not to like?

Related articles

-

Blog: Pointing out the possibilities at Pontio

ip

Reflections from FRSA Peredur Williams on his rapid engagement with RSA Fellowship and how one event led to impact

-

Developing through social enterprise

Jonathan Schifferes

This is a guest blog by Kate Swade of Shared Assets, reflecting on the Developing Socially Productive Places conference at the RSA, 2nd April 2014.

-

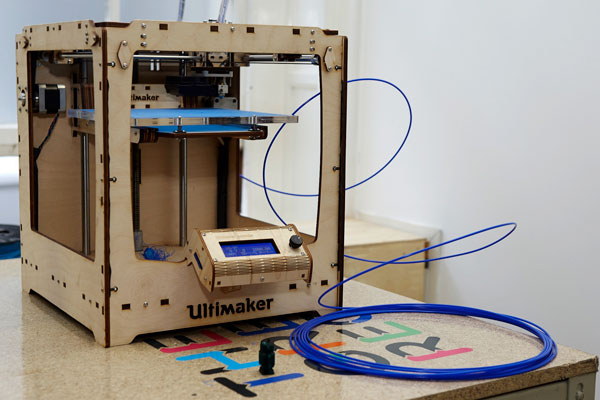

Makerhood: revitalising neighbourhoods through the art of making

Benedict Dellot

In this guest post, the team at Makerhood describe their efforts to create a community of makers in Lambeth. Find out more by visiting their website.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.