Occasionally it can feel as though there are a thousand and one ways of making sense of the world. That is, of understanding why people think and behave in the way that they do and of knowing what can be done to help people live the lives they want to lead. Not a month goes by without the publication of another book telling us about the most important thing we need to know if we want to solve our problems – be it the importance of willpower, the power of ‘influencers’, the art of taking things more slowly, or of the significance of ‘group-identity’ and belonging.

While some of these ideas are no doubt useful, it can be a struggle to keep track of all the lessons that are supposed to help guide our day-to-day actions. Indeed, many end up competing with one another for our attention, and often it is the salient ones that triumph over the most important. Hence the nod to Malcolm Gladwell's work on 'influencers' just now.

To find our way out of this maze of different concepts, it can be helpful to take a step back and try and view the whole picture. In practice, this means drawing upon a set of ‘meta concepts’ through which to make sense of the world. These aren’t lessons or rules as such, but more ‘lenses’ that can be applied to view different issues more clearly.

At the RSA, there are a few lenses that are either dominant or emerging. Here’s a brief summary of three:

Cultural Theory

Cultural Theory tries to make sense of problems by viewing them in terms of the different ‘cultural understandings’ that are at play. First conceived of by the anthropologist Mary Douglas during her studies of different communities in Africa and elsewhere, Cultural Theory suggests that there are four dominant understandings that can be found (to varying extents) in different groups and areas: egalitarian, individualist, hierarchical and fatalist.

Whether these different cultures are present depends upon two different criteria: Grid and Group. Grid relates to the importance of rules and structures, whereas Group refers to the importance of collective control and consensus. Where there are high Grid and Group orientations, we find hierarchical cultures. Conversely, where there are low Grid and Group tendencies, we find individualist cultures.

The message at the centre of this theory runs as follows: efforts to address challenges need to draw upon and broach all of these different cultural understandings if they are to effect change. Since every community contains some element of Grid and Group, efforts at tackling problems are unlikely to bear fruit unless they accommodate each perspective. We need a mixture of rules (Hierarchicalism), norms and community values (Egalitarianism) and incentives and support structures (Individualism). Matthew Taylor recently used the example of cash-in-hand work as one particular challenge that could be better addressed by applying the lens of cultural theory. To date, we have an overtly ‘elegant’ hierarchical approach (through sanctions and inspections), at the expense of egalitarian (nurturing tax fairness) and individualist ones (tax/benefit incentives).

and Clumsy Solutions: the Role of Leadership'

Mental complexity

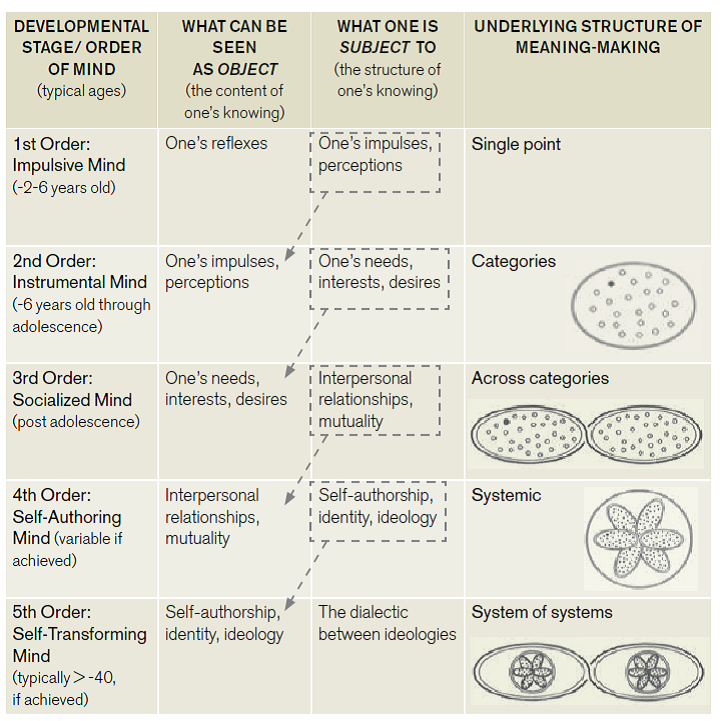

The notion of mental complexity was developed by the Harvard professor Robert Kegan some years ago. Mental complexity refers to how we know, not just what we know. Kegan identifies a number of stages of mental complexity (or ‘adult development’), each of which offer people greater scope to see things objectively rather than subjectively. See the graph below.

This ‘subject-object’ relationship is important. When we take things as subjective, they ‘have us’, whereas when we take things as objective, we ‘have them’. The difference is between being caught in the grip of something with your blinders on, and being able to take a step back and get some perspective. Kegan uses the analogy of the scriptwriter vs. the actor. The actor follows the lines and is caught up in the minute-by-minute action, whereas the scriptwriter views things from afar and is able to edit the script as they see fit.

In short, higher levels of mental complexity give people a greater awareness of their emotions and attitudes and allows them to take more measured decisions. When applying this lens to view different issues, it prompts us to think about whether people are mentally ‘up to the task’ of undertaking the behaviours and actions we expect of them.

One example of where this has been used to make sense of an issue (beyond the territory of organisational management) is the RSA’s work on the Big Society. Our argument, published in a report earlier this year, is that the Big Society presents people with a ‘hidden curriculum’ of emotional and relationship-based tasks that require a certain order of mental complexity – the ‘self-authoring mind’ – which the majority of the population do not hold.

Values Modes

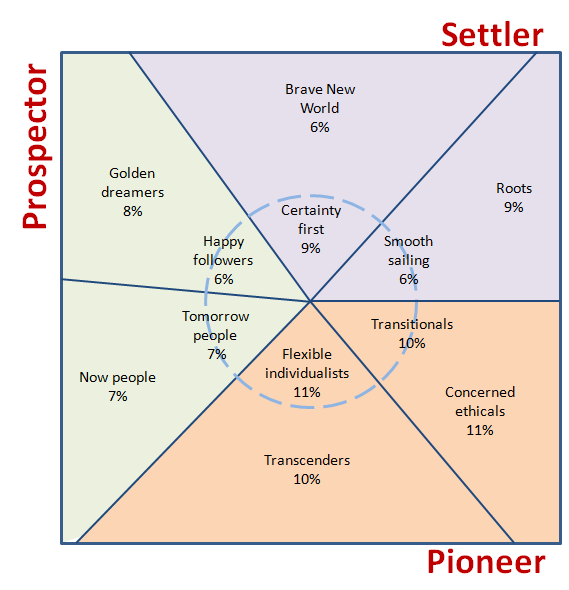

The concept of Values Modes suggests that there are three main value groups: Settlers, Prospectors and Pioneers. Where you fall within each of these groups depends upon the extent to which you are ‘sustenance driven’, ‘outer directed’ or ‘inner-directed’ (there are sub-groups to each of the main three). Settlers, being primarily sustenance driven, like stability and security; Prospectors, being outer-directed, look for things that confirm their identities and boost their self-esteem; and Pioneers, as mostly inner-directed, seek out the new and novel.

Two of the foremost proponents of Values Modes, Chris Rose and Pat Dade, argue that used in the right way, it can be an invaluable tool for understanding how different policies and initiatives are likely to affect people’s behaviours. For example, one of their key arguments is that you have to tailor initiatives and messages to fit different value groups. You can’t expect to heavily influence a Settler’s behaviour by showering them messages about new trends. Highlighting social norms would be more appropriate, but then this wouldn’t do as much to shift the behaviour of Pioneers who are less concerned about what other people are doing.

'The Big Society: Why values matter'

Related articles

-

Design for Life: six perspectives towards a life-centric mindset

Joanna Choukeir Roberta Iley

Joanna Choukeir and Roberta Iley present the six Design for Life perspectives that define the life-centric approach to our mission-led work.

-

Inventing meaning and purpose: a politics award for our times

Ruth Hannan

Ruth Hannah is inspiring you to submit your creative and courageous political project to the Innovation in Politics Awards 2022.

-

How can we cultivate healthier and happier communities?

Ella Firebrace Riley Thorold

How might we look to our futures and shape what it means to lead healthier and happier lives?

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Hi Matthew,

The battle between situations vs personality dispositions as an explanation for our behaviour is a fascinating one.

Walter Mischel - the Marshmallow test guy - must've thought his 1968 situationist attack on personality approaches was a hammer blow, with its finding that correlations between personality and behaviour are around .30 - a rather weak relationship.

But it would only later emerge that the classic situational effects in social psychology (bystander intervention etc) in fact all came in at under .40 themselves!

Personality does a better job when behaviours are aggregated over situations too.

It turns out, also, that there are 'strong' situations and 'weak' ones - in unstructured and novel situations people behave less similarly, compared to situations with strong constraints on behaviour, and cues.

So, the tide turned against Mischel's situationism; today most social psychologists acknowledge the personality dispositions can explain variations in behaviour that situations can't explain - ie interactionist approaches.

It's particularly odd that the arch-situationist Mischel did pioneering work with the Marshmallow test (ie ability to delay gratification).

For someone so keen to disprove the existence of enduring personality traits, he did an awful lot to prove that there is a personality capacity that generalises across time and across situations!

And surely his Marshmallow test relates to Prof Terrie Moffitt's self-control, Loevinger's ego stages and Kegan's stages too...

The RSA Library has a copy of Chris Rose's Values Modes book 'What Makes People Tick - The Three Hidden Worlds of Settlers, Prospectors and Pioneers' - take a look. Though you should talk to Pat Dade about it all some time - he's the source of it all...

I know the related model of Spiral Dynamics model puts 'Life Conditions' at the heart of its explanation for changes - which is quite situationist.

The 4 most common 'value memes' in Spiral Dynamics are characterised by:

- fatalism

- hierarchy

- individualism

- egalitarianism

It's fairly hard to not to spot an overlap with Cultural Theory.

Of course, there is further shift sometimes seen after egalitarianism, towards Integral approaches - which are able to integrate the previous approaches.

Cultural Theory denies that another way of organising can exist - whilst simultaneously extolling the virtues of a novel 'clumsy' way of organising that integrates the others.

From my point of view, that merits being seen as an emerging way of organising.

Matthew M

Thanks Ben for this. The interesting question is the

relationship between these theories; are they alternative accounts or can they

go together? In fact, each claims to measure something different. Although the

relationship to grid group theory complicates matters, I see Cultural Theory as

primarily about knowledge and power rather than types of people. There are

different and conflicting ways of seeing the world and of pursuing change. The

degree to which these perspectives will be adopted is influenced by context

(the nature of the organisation or of the challenge it faces) and the

predispositions of those involved. However, the four core perspectives are

universal in the sense that at various times we all adopt hierarchal,

egalitarian, individualistic and fatalistic responses. And, crucially, the

perspectives have their own dynamic in that they tend to react against each other.

The relationship between Values Modes and cultural

theory's paradigms: prospectors seem to be most inclined to be adopt

individualist perspectives, pioneers are more egalitarian in their ambitions

while settlers are more happy to accept the stability and order offered by

hierarchy. Having said this the fit is far from neat. I need to find out more

about the Values Mode approach because I am instinctively sceptical about the

implication that what drives behaviour is a type of personality rather than the

interaction of predisposition and social context (in this regard it is worth

remembering the situationist implications of the experiments of Milgram and

Zimbardo).

I find it easier to find a meeting point between cultural

theory and mental complexity in that an understanding of the inherent and

personal tensions between different world views and of the value of respecting

and seeking to combine these seems to me to be an excellent example of mental

complexity. It is important therefore to emphasise that the achievement of

greater mental complexity lies not in discovering a single truth but in living

with inherent plurality and complexity.

Thanks Jan. I'd be interested to read more about this if you have any written materials you could send through.

[email protected]

Thanks Josef. I'm reading bits of Jonathan Haidt's the Righteous Mind and Kohlberg is mentioned a few times. If you're interested in this kind of thing, it's worth checking the first chapter out as Haidt gives a interesting critic of Kohlberg's stance.

Thanks Matthew.

I'll check out the paper.

A publication like the one you mention would be interesting to commission. The common concern with these 'meta concepts' is that they sound good in theory but are a little too difficult to translate into solid policies. Any report that lays out some tangible recommendations would be welcome.

It's worth highlighting the various political difficulties that arise when people try to use these concepts. For instance, in Keith Grint's papers he writes about the urge for policymakers to treat 'wicked problems' as though they were 'tame' or 'critical' - the reason being that few leaders want to be seen as slow and indecisive. Likewise, with regards to mental complexity, the best thing might be for politicians to discuss long-term adult development courses (the idea of these need to be fleshed out), but what attracts voters is easily understandable 'elegant' policies e.g. the training of 10,000 community organisers and a national big society day. Not to say these are not worthwhile but they need to be married with something more substantive.

Ben