When it comes to climate change, creativity is not optional. To retain a resilient and livable planet, we need to do things differently, better, and quickly. In light of our competing commitments to energy security and fuel prices, that means rethinking our ends, our means, and our conception of ourselves.

Despite my reservations about Adam's attack on the political class and my concern about creativity being hollow, I have enjoyed thinking about what it might mean to link our new agenda on climate change with our emerging worldview.

A broader conceptual discussion about creativity is needed, but for now, with creativity understood as self-directed, pro-active and innovative activity, here are some thoughts on what 'the power to create' might mean for attempts to tackle climate change.

Writ large, our current approach to climate change is passive rather than creative. Most of us follow the routines of our lives, point the finger at politicians, do a few tokenistic things like recycle or use our own shopping bags, demand cheap and secure energy without realising that's a climate position, hope for the best at big international climate summits and wait for another IPCC report or devastating storm before saying: isn't it terrible that nothing is happening? We can do better, and here are six ideas on how an emphasis on creativity might help:

1) Frame the power to create as a solution to stealth denial

If passivity is a large part of the problem of 'stealth denial' creativity may be part of the solution.

(Our report unpacks the claim that about two thirds of the population are in stealth denial on climate change, i.e. they accept the significance of human-caused climate change, but don't live as though they do.)

Creativity is about more than DIY, but I was struck by the importance of passivity as a contrast with creativity while reading George Monbiot's piece in today's Guardian:

"Almost universally we now seem content to lead a proxy life, a counter-life, of vicarious, illusory relationships, of secondhand pleasures, of atomisation without individuation...Perhaps freedom from want has paradoxically deprived us of other freedoms. The freedom which makes so many new pleasures available vitiates the desire to enjoy them... Freedom of all kinds is something we must use or lose. But we seem to have forgotten what it means."

Perhaps that's too rhetorical, but the idea seems sound: large chunks of the population have become so busy focusing on work, family, bill-paying, domestic chores, and entertainment, that we lack the requisite will, time and energy to think about - never mind act upon - 'bigger-than-self problems' like climate change.

Given that climate change is not exclusively 'an environmental issue' one role for creativity is to highlight the scope for people to act in ways that they might not have previously imagined to be relevant. This includes wasting less food, flying less, eating less beef, and a myriad of other micro behaviour changes. However, the point of our recent report is that we clearly need to connect such acts to a credible narrative about the big picture of continued fossil fuel production and steadily rising global emissions.

In that respect, you should find our who your MP is (most don't know) and tell them that climate change matters to you, but you might have more impact by finding a few hours of gumption to change your energy supplier and then use social media and email your friends and colleagues to explain why.

As far as possible (not always very far if you are in poverty, a full-time carer, unskilled etc) we need to seek to solve the problems of our lives rather than waiting for them to be solved for us.

What might that mean more tangibly? Others might disagree, but to me it points squarely to Shorter working weeks which means a revaluation of the core economy. Without that shift, most people simple don't have the time and support required to be more creative.

2) Get creative about our ends as well as our means.

If we are stuck with indefinite economic growth that is parasitic on undervalued and scarce natural capital as our chief measure of societal success, then the power to create is unworthy of the name. The 'power' in 'power to create' should be about contesting the rules of the game as well as playing it better.

The 'power' in 'power to create' should be about contesting the rules of the game as well as playing it better.

In this respect, is it not just sane to think we need a conception of economic maturity that connects to an idea of human rights and respects planetary boundaries? Can't we have a political discourse where people speak about economic decisions as if they are also social and ecological decisions, which they are? Getting seriously creative about how we conceptualise 'change' means breaking down the distinctions that falsely keep these dimensions of our world apart.

3) Place our hope in cities as well as States

Some say governments are now too small for the big problems (e.g. climate change) and too big for the small problems (e.g. anti-social behaviour), and the time of cities has come.

An uncreative approach to climate change is to wait for international agreements between states. Given the divergent economic needs, different energy reserves, vulnerability to climactic changes and range of national political systems, we are never likely to get a global agreement (that satisfies, say, USA, China, India, small island states, Norway, Russia) that goes beyond a firmer resolve to reduce emissions in principle(which is not to say we shouldn't try).

In the meantime we can act at levels where the impact is more tangible - cities. As Benjamin Barber put it in the RSA Journal:

"It turns out that about 80 percent of all energy is used in cities and 80 percent of global carbon emissions come from cities with more than 50,000 people. Therefore, if cities take strong measures – as well as Amsterdam, Los Angeles cleaned up its port and reduced carbon emissions by 30 percent to 40 percent - they will have a profound effect. Even if the US and China do nothing, cities can have a big role to play in fixing the problem. It's not just a theoretical thing."

The connection between cities and creativity is well established, and our hope for creative action on climate change may lie at this level of the Polis.

4) Trust creative artists to help communicate climate solutions

As this recent piece indicates (HT Jonathan Schifferes), climate communication has not so far been very successful, and there is a place for artists not just to change the message but also the medium: "People respond to authentic artistic expression, not scripted messaging. Artists need free rein. Businesses should take the plunge and give it to them."

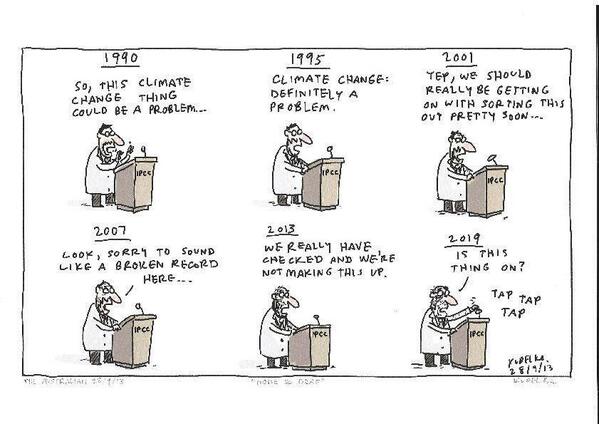

This might sound a little worthy, but as indicated in 'Divided Brain, Divided World: Why the best part of us struggles to be heard', we are in danger of being over-literal and half-blind in our attention to the world, and we need artists of various kinds to help us retain a sense of balance and perspective: This cartoon helps put this point in perspective:

Perhaps 'power to create' is precisely what we need for the third industrial revolution.

5) Trust in a radical decentralisation of energy provision.

This point is covered in more detail as one of our eight suggestions for how to overcome climate stealth denial in the report (see pages 56-58):

Not only do we need a transition to renewables, but we need to design the energy

infrastructure in a much less centralised, vulnerable and remote way, as suggested by Rebecca Willis and Nick Eyre of Green Alliance:

‘Only 50 years ago, most households were directly aware of the amount of energy they used from the weight of coal carried into the house. Today it flows in unseen through pipes and wires, and embedded in the multitude of products purchased, most of which are manufactured out of sight from consumers. The pervasive attitude that new energy infrastructure should not be seen may well be one of the reasons behind opposition to

renewable energy installations. But a sustainable energy system will not be an invisible system. Reconnection of people with the energy system is a precondition for the low carbon transition.’

The power to create could be about that reconnection, with more homes being power plants, and more communities collectively managing their localised and renewable energy. Perhaps 'the power to create' is precisely what we need for the third industrial revolution.

6) Divest in centralised dirty energy and reinvest in decentralised renewable energy, thereby supporting the forms of innovation we need (see page 53-54).

If the power to create means challenging vested interests, the best way to do that is to move your money accordingly. The test of the RSA's resolve to challenge vested interest will be questions like this one.

These six ideas are a way of showing how 'the power to create' might help to flesh out what the call the action on climate change might mean. In essence the point is this: it's not hope that leads to action, but action that leads to hope.

Dr Jonathan Rowson is Director of the Social Brain Centre at the RSA and author of the recent report: A New Agenda on Climate Change: Facing up to Stealth Denial and Winding Down on Fossil Fuels. He Tweets @Jonathan_Rowson

Related articles

-

Blog: Trying to behave myself - a Social Brain Odyssey

Jonathan Rowson

In his final blog, Jonathan Rowson looks back on his time at the RSA and our behaviour change work.

-

New Report: The Seven Dimensions of Climate Change

Jonathan Rowson

A talent for speaking differently, rather than arguing well, is the chief instrument of cultural change – Richard Rorty

-

Seven Serious Jokes about Climate Change

Jonathan Rowson

Comedy is simply a funny way of being serious - Peter Ustinov

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Actually I may have misunderstood you—did you mean to hypothesise that lay "believers" (who are in "stealth denial") personally use "casual disregard and attacks on people assumed to be conventional 'climate deniers'" as mechanisms for procrastination?

If so, this is an even MORE plausible and potentially important idea than the one I thought you were suggesting!

The blaming of inaction on unseen forces of denial—much as various past and present societies have posited a conspiracy by members of a particular Middle-Eastern/European ethnoreligious minority as an excuse for their own disappointing rates of progress—is almost certainly a retardant of progress in and of itself.

One can't help but think of that inexplicably popular alt-history thriller by Oreskes and Conway called "Merchants of Doubt," whose thesis is that world action on climate change has been stymied by the clandestine machinations of a cabal of four profiteers called... almost too perfectly... Seitz, Singer, Jastrow and Nierenberg! I trust it's unnecessary for me to name the notorious tradition of human thought of which Oreskes and Conway's conspiracy theory is a seamless continuation, though I can't resist mentioning that my fellow "skeptics" tend to refer to the novel either as 'The Protocols of the Elders of Doubt,' or simply 'Merchants of Venice.' Has any movement which blamed its difficulties on an elite handful of secret supervillains (of any race) ever overcome those difficulties? To my knowledge, no—not without growing up and taking a long hard look in the mirror.

Anyway, both "versions" of your "strange" theory are promising, if you ask me!

Keep seeking—that's the best we can ever be expected to do as intellectual bipeds.

Nothing strange about that hypothesis! It's prima facie logical, and sounds like a very promising line of investigation for your future work if you ask me. If you do manage to establish that signs of anti-heretical zealotry on the part of the, well, establishment "side" reduce not only its moral likability but its legitimacy in the popular mind, and [thereby?] let the lay "believer" off the hook when it comes to his or her own feelings of duty, then you may well have identified not only an important factor in what you call "stealth denial," but also an urgent lesson for the climate "establishment": hey guys, if you want to change the world's behavior you have to behave in the most moral way possible yourself.

I'll let you know further thoughts after reading the report. So far I'm impressed by your openness and your careful reasoning (though I think you "dumbed down" these qualities excessively in your blog posts), so your pessimism about impressing me may turn out to be misplaced! I've never had much against people who disagree with me on The Science™, or indeed much "for" people who agree with me on it—what really matters to me is that we all play by the same rules of honesty, both to ourselves and to others (in a single word, "skepticism"). I particularly like your upfront acknowledgement of the activist or rhetorical raison d'etre of your reports—since everybody is "guilty" of this, by far the most honest policy is to come out and say so.

Thanks again for a nice conversation about this, Dr Rowson.

Thanks Brad. You are right; for a new concept in a relatively charged subject some consistency would help, even(or perhaps especially) in a blog post.

I genuinely look forward to hearing what you think once you've read the report. I am sure you won't be entirely impressed(!) but I expect your comments will be helpful.

(It might seem strange, and this is stretching the concept even further, but I think casual disregard and attacks on people assumed to be conventional 'climate deniers' is part of the way those in stealth denial procrastinate on closing the gap between their intellectual position and their actions. It's a way of displacing the problem.)

Dr Rowson,

Thanks for your very thorough explanation of concepts that I may have avoided confusion about by reading the report for myself! Unfortunately it wasn't obvious to me where the report actually was, and as it sounded fairly academic I assumed I didn't have access to whatever journal it was in. I'm pleased to have found it freely downloadable just now, and shall read it as soon as I can. Please forgive any previous remarks that seemed like attempts at "killer blows to a considerable amount of work conducted in good will." Your candid and helpful answers distinguish you from some of the obtuse, obscure and bad-faith climate-heresiological "scholarship" with which I was a bit too quick to stereotype you.

Lastly, assuming that this is the definition of stealth denial you actually used in the report (and note that it's not quite the same as any you've mentioned hitherto)...

"those who say they think climate change is happening, caused by humans and a threat worth addressing, don't appear to have commensurate feelings or actions"

... then it might be a good idea to use this consistently when discussing the report—even in blog posts! It's still succinct enough for such informal contexts, but has more logical rigor than the previous attempts to capture the idea.

Thanks again,

Brad

Brad,

Thanks for taking the time to comment in detail.

First on terminology. You make a perceptive point. in the report I make it cleat that the phenomenon in question is best captured by the term 'disavowal', but on reflection chose 'stealth denial' because it is less obscure and technical and more accessible and potentially impactful.

Unlike Academic papers, reports from organisations like the RSA combine a commitment to rigour with the aim of influencing opinion, and that is reflected in the choice of terminology for titles and concepts.

In this case, to deny by stealth is not to deny covertly or undercover, but to deny de-facto through actions, despite what you profess to believe. In this respect the denial is manifest in the everyday conventional and socially acceptable actions, not in the beliefs- which is why we call it stealth denial rather than 'stealth acceptance' which you suggest.

I also think - despite your comment - that it is a coherent term. Covert is not the only meaning of stealth. It is also about being furtive or unobtrusive - which is precisely my point. Lots of people who wouldn't want to be thought to be climate deniers, might as well be in terms of the impact that preference has on their behaviour.

Still, stealth denial as we construe it is a complex theoretical notion that does NOT (and I was very open about this in the report) lend itself well to being precisely measured through the blunt instrument of a national survey. Still, our questions arose from a close reading of existing research on climate disavowal, which I referenced and which I would encourage you to look at.

On the methodology, if you see the appendices of the report, we did some work on construct validity to do the best we could to connect what is essentially a psychoanalytic construct with national survey questions - but nowhere do we call this a final and definitive verdict.

The aim was rather to give a name and a provisional number to something that is widely known but rarely spoken about- that those who say they think climate change is happening, caused by humans and a threat worth addressing, don't appear to have commensurate feelings or actions.

In response to your claim that you can say yes, no, no, no and not be inconsistent I say I disagree, but I also fully accept that this IS a normative position, and I am completely transparent about that in the report.

You are clearly insightful, and I respect your right to robustly disagree, but I also don't want to waste time responding to facile arguments presented as killer blows to a considerable amount of work conducted in good will (e.g. I would hope it was obvious that I know that the 'reality of climate change and the 'significance' of it might be different.)

If you are going to respond, please have the courtesy to consider the degree of care taken with language in a blog post, and blog comment and the purpose and methodology of a report with an openly normative agenda.