In short, it depends – but if you’re a woman in the UK, the odds aren't in your favour.

Earlier today, Ed Miliband unveiled plans to beef up vocational education by introducing new technical degrees if Labour wins the election in 2015. His aim is to increase the number of people in higher level apprenticeships by at least 100,000 and raise the profile of vocational education among young people aged 16-19.

Miliband isn’t exactly treading in unchartered waters - apprenticeships are already central to skills strategies across the UK’s cities. Employers have steadily warmed to the idea of taking on apprentices as the evidence demonstrates returns in terms of productivity and long-term value for money. For example, trainees in British Telecom’s apprenticeship scheme were found to be 7.5 percent more productive than non-apprenticeship trainees. The company also reported it made a profit of £1300 per apprentice per year.

However, there is reason to be cautious about the current vogue of apprenticeships being seen as a panacea, given their poor returns for those hoping to progress while in work. A recent and comprehensive review of apprenticeships found their impact to be limited for many individuals. Explanations for this vary, but the following is typically cited: weak provision of information, advice, and guidance (IAG); diminished overall quality due to an absence of employer involvement and support; and wider barriers such as cost, accessibility, and poor attitudes of schools, friends and family.

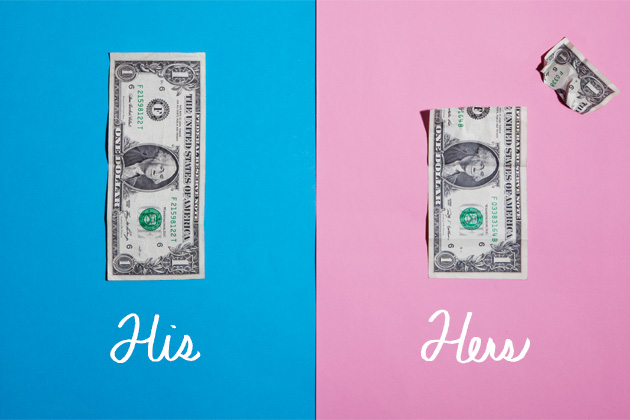

According to research from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, too much of the growth in apprenticeships appears to add to the stock of low-level training programmes for workers in low-skilled, low-paid jobs with few progression prospects. In particular, women and minorities are least likely to take up apprenticeships that lead to new skills and advancement in their careers. Where women are represented in Advanced and Higher Apprenticeships, this actually reflects the high rates of conversion (the practice of ‘converting’ current employees into apprentices by accrediting existing skills rather than introducing training for new skills) among female employees. The reality is that many women are gaining qualifications for the work they already know how to do and have been doing, rather than completing training needed to perform their jobs or jobs which are more valuable to employers. This means that in spite of having apprentice status they remain at a standstill in employment.

Women tend to be over-represented in low-skilled, low-paid part-time work, which is why it is particularly concerning that that they experience limited returns from apprenticeship qualifications in terms of progression in employment. Women, especially mothers, older women, and women from certain ethnic backgrounds, are found to be at a disadvantage when it comes to getting a foothold in the labour market, let alone a rung up. Their potential to contribute more to the world of work is enormous, however; in a study by Sheffield Hallam University, 53 percent of the women surveyed who were working in low-paid, part-time jobs were under-utilised in the workplace – they had previously worked in a job with more pay, responsibility, or both.

In Human Capitals, the City Growth Commission’s latest report, the case for addressing skills mismatches, particularly under-utilisation, is made by highlighting the potential for greater productivity and competitiveness. Better utilising the skills of women in the workforce will certainly help to drive economic growth, but properly investing in on-the-job training for women so they can move up and give more in return will also go a long way for the public purse. The government now spends more on benefits and tax credits (£3.23bn) for families in work than it does for unemployed families. If apprenticeships reliably offered women in low-paid jobs a viable pathway to career and wage progression, more women would be recognised as the assets to economic growth that they are, rather than as liabilities.

Brhmie Balaram is a Researcher for the City Growth Commission hosted at the RSA (@Brhmie)

This blog was originally posted on the website of the City Growth Commission. You can follow the City Growth Commission @citygrowthcom

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.