Earlier this week, the Bank of England confirmed something the RSA has being arguing time and again: that the growth in self-employment is not simply a response to a lacklustre labour market, but rather a phenomenon borne out of deeper structural trends occurring in our economy. As their analysis shows, an increasing number of people are making a positive choice to work for themselves.

Here are three findings that led to their conclusion:

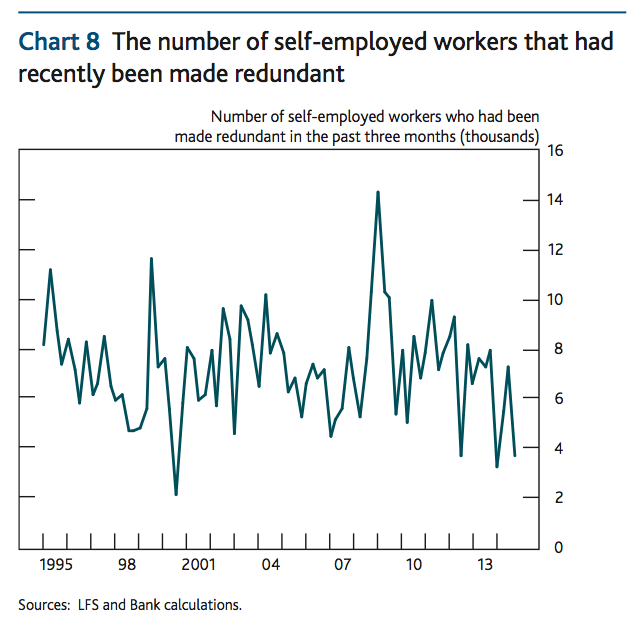

1. There is no significant link between redundancies and self-employment

The graph below shows that the number of self-employed who said they started up in business following redundancy did not rise significantly after the economic downturn, except for a temporary sharp spike in 2009. The Bank of England calculates that the average figure between 2008-14 was only marginally higher than the long-term average before the recession.

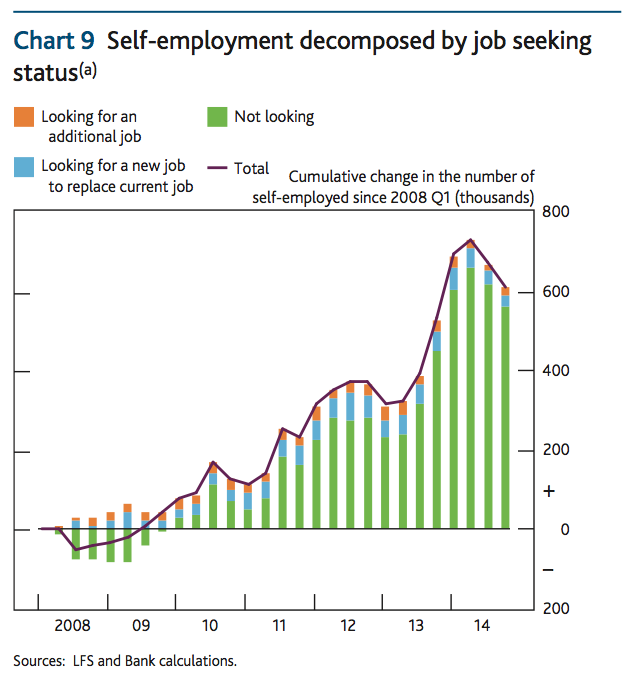

2. Few of the newly self-employed are looking for other work

If people were moving into self-employment out of economic necessity, it would be reasonable to expect these new and reluctant business owners to be searching for other work. Yet this story does not bear out in government data. The graph below shows that only 9 per cent of those who moved into self-employment after 2008 were looking for an additional or new job. In fact, the proportion of the self-employed who were interested in other work in 2014 was actually slightly lower than the proportion of employees thinking of departing their workplace.

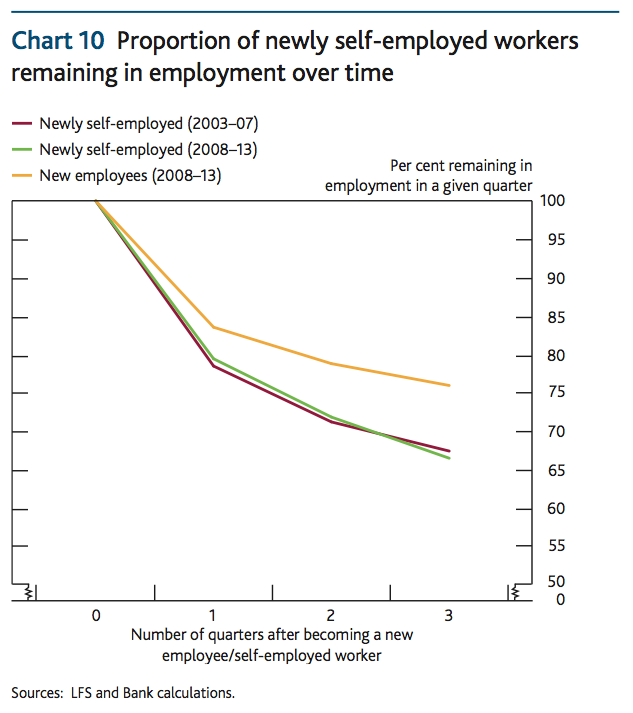

3. The newly self-employed are no more likely to cease trading shortly after starting

If the above findings weren’t convincing enough, the Bank of England’s analysis also reveals that the newly self-employed have stuck around in their new roles just as long as those who started in business prior to the crash. The graph below shows that around two thirds of those who started in business between 2008-13 remained self-employed after three quarters, which is more or less the same proportion as those who started between 2003-07. In other words, the newly self-employed are no less determined or competent than their predecessors.

Of course, none of this is to say that every self-employed person wants to work for themselves. As the Bank of England points out, both our own RSA/Populus survey and that of the Resolution Foundation find that around a quarter are reluctantly self-employed or pushed into this position in a bid to escape unemployment.

Nor do the Bank of England’s findings say anything about how the self-employed fare in terms of their financial health and wider standard of living. Indeed, an upcoming RSA and JRF study will highlight a number of perils and pitfalls that the self-employed have to endure (even if they overwhemingly prefer to work for themselves).

Yet what the Bank of England’s analysis does do is throw cold water on the increasingly flaky notion that the growth in self-employment is a pernicious trend to mourn over.

Follow me on Twitter.

Related articles

-

The self-employed: rich, poor or something more?

Benedict Dellot

Barely a week goes by without another news story charting the fall of self-employed earnings. But how much do the headlines match reality?

-

5 tax reforms to create a more entrepreneurial society

Benedict Dellot

Small businesses don't want sweeping tax cuts and special favours. They want a tax system that is clear, fair and progressive. Here are 5 ideas to get us started.

-

Blog: A Budget of boons for the self-employed

Benedict Dellot

Hidden away in the Budget Red Book were several announcements to satisfy the self-employed

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.