Devolution to cities and counties across the UK is gathering pace. Ultimately, all the technical talk about budgets, powers and new governance structures comes down to this: increasingly, it’s going to be up to places themselves to develop and follow their own strategy for social and economic development, spending their own money. With broad consensus on devolution, the question then becomes ‘what makes a successful place-based strategy?’

In trying to develop successful strategies, places will realise valuable advantages if they can draw on heritage and identity locally. Most simply, as economic development strategies follow a frustratingly similar formula, and global brands increasingly dominate the public realm, local history is a USP. For example, heritage and memory is a principal advantage that high streets have over online retailers.

As much as a city might look forward to new industries, new developments and a brave new world, cities have to find their niche in a national ‘system of cities’, and an increasingly globalised markets for what they produce, attracting and retaining the people they need to produce them. Bruce Katz is fond of quoting Dolly Parton: “find out who you are, and then do it on purpose”.

This is more difficult than it sounds. Firstly, because of our ‘heritage’ of highly-centralised government, many places will be doing this at a scale they haven’t seen before. Many agencies themselves, such as LEPs, are new. Secondly, devolution means a system where different places have different powers on different timescales. Beyond Greater Manchester, it often isn’t clear who will be in the driving seat, or indeed how many seats are needed to successfully drive. And thirdly, heritage means a variety range of different things to different people.

In the new era, to be successful, place strategy must be linked to the identity of a place – but places don’t have single identities. But as soon as we talk about authenticity and identity, we must make decisions about who participates, what we include, and how we represent those contributions. Our heritage, broadly defined, is everything that has happened in a place (and to its people) up until now.

Building on our work last year, we will this year (with support from Heritage Lottery Fund) outline a constructive process by which heritage can play a pro-active role in place strategy. But to achieve impact and influence our project will ultimately demand some soul-searching. Lots of people love the idea of building a place strategy based on local assets (new and old); but place leaders end up commissioning place promotion agencies.

While a more strategic approach to heritage can help to fill the ‘identity gap’ at the heart of many place shaping efforts, we must understand how the identity gap matters to the bottom line and to citizens. Place strategies, and the market-oriented investors and investees who are responsible for putting plans in action, seem most interested in speaking the language of global business. I’m not sure this is irrational, given the increasing vulnerability places have to (and reliance they have on) attracting and retaining globally mobile flows of capital and labour? (Alternative focus, on anchor institutions and local economic flows, is important; but to address social equity they need to be coupled with ways of redistributing wealth which exists unequally across the country). Finally, heritage faces an uphill struggle to make its case: the recent collation of evidence by the What Works Centre for Local Economic Growth basically found no evidence that sports and culture facilities and events (including heritage) have any discernible economic impact.

So the even more strategic approach, therefore, might consider “who is a place strategy really for?” We’d expect strategies to prioritise and rely upon the contributors to the strategy-making process. To be integral to the development of a place, heritage must be integral to the development of the plan. To be integral, the strength, breadth and depth of networks will no doubt prove a crucial factor.

Having it both ways – portraying an image of modern dynamism built on historical richness – is a canny achievement. The City of London has managed it (with 30 years of continuous service by this man) but it can look brutal from street level: New York planners tried to cleanse Chinatown restaurants of incorrect English to help win an Olympic bid; A bed and breakfasts in Yorkshire was marked down by the tourist board in their ratings for ‘too much chintz’ (in a B&B!).

It’s easy to romanticise the ‘local’ - and increasingly lucrative too. National and global entrepreneurs are already taking a pre-emptive step in speaking the language of authentic localism: your new swanky chain restaurant might be more sophisticated at projecting its connection to local heritage than independent competitors.

To build capacity for making the most of heritage, I suggest we support a culture of DIY activism to enable people to (re)present local history, and connect people to their place in new ways. The strategic role of funders and government might be to support the kind of stuff which taps into people’s power to create.

There’s a chance to use new technology: Historypin has seen 50,000 people put 350,000 historical items on a world map. Spacehive is like Kickstarter for civic projects in places: one listed building has attracted £335,000 from 357 funders (including HLF)

But most inspiringly, we want to learn about the efforts to appropriate and reinvent the traditional. In Cambridge, people have made their own blue plaques of previous residents (an RSA initiative from 1867). Displaying everyday history in your own window changes the vibe of the street more than a dead celebrity plaque does in Westminster.

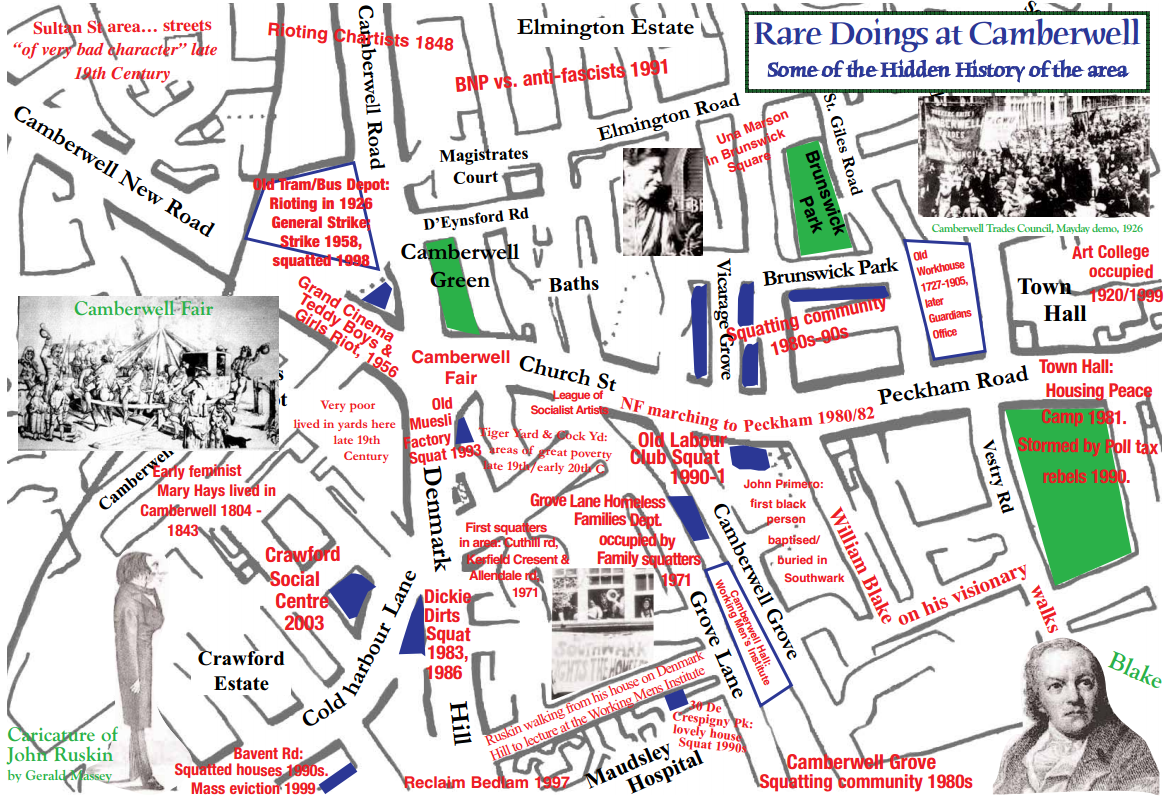

When I moved house last year I was handed a Travel Guide in the town centre by the Council-funded SE5 Forum. Its centrefold is a map: an inspiring ocean of social activism over the years. It totally grounded me in the social heritage of where I’d moved to – more invisible than the buildings I pass every day – and I felt a responsibility to people who’d taken social action there in the past to get themselves on this map.

We’re glad to be part of this important conversation about the forces at work in place shaping. We want your input and inspiration too. We’ve all got our place in place heritage. Email me your perspective at [email protected]

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.