Previous examples of projects that have planned to use heritage assets to help build stronger, more lively places are numerous. Yet not many get independently evaluated after the project has finished, let alone attract serious academic study. Today the Grainger Town Project is widely regarded a demonstration of ‘what works’ and, perhaps more importantly, the town is now seen as the ‘Pulsating Heart of Newcastle’.

Such case studies are vitally important for research. In the natural sciences, especially Biology, researchers explore questions about life through the use of ‘model organisms’ or ‘model systems’ such as the fruit fly, or the laboratory mice. By using comparative systems scientists can better explain experiments by reducing variable and importantly such experiments can be more easily replicated by other researchers. The notion that such models systems aid in our understanding of life, is also being extended to human rights, where ‘best examples’ drive aid projects, and even academic study itself[1]. To some extent, the Grainger Town Project is just such a ‘best example’.

Why? For three reasons - firstly, the Grainger Town Partnership set out to do something and then did it; secondly, the project delivered, or exceeded, on numerous social and economic targets with quantifiable measures; and thirdly, it has been the study of at least two academic level evaluations confirming the success.

Grainger Town covers around 36 hectares in the centre of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne. Much of the historic buildings were built by Richard Grainger between 1824 and 1841. From around 1970, developments on the outskirts of the city centre drew many business out of Grainger Town leaving many floors empty and much of the area began to fall into disrepair.

The Grainger Town project was established in 1997 with the broad remit to support the comprehensive regeneration of the historic town center; specifically the preservation of ‘Tyneside Classical Architecture’. The project was backed by a consultancy strategy that formed the basis of a ‘Single Regeneration Budget’ (channeling EU funding) that would finish in 2003. Together with English Partnerships, English Heritage and the Heritage Lottery Fund, the project worked to lever-in private sector investment into the town center.

Yet this strategy was far from purely economically focused - it also contained strong social and cultural foundations designed to improve the quality of life and environment. They wanted to develop the area to make a lively place for people to live and work - somewhere clean, safe and with a heritage that the community could feel proud about.

The partnership worked to improve confidence in the area by investing in the public realm to demonstrate commitment to the private sector and thereby attract further funding. Such work amounted to around £7.7m to provide a more attractive environment for local business and people to come to. The total public expenditure was over £45m.

The Grainger Town Partnership is largely credited for the success of the project, as you might hope. Importantly, it was the integrated approach of their efforts that made the impact. Rather than a top down approach of informing local communities and stakeholders of the project goals, they engaged with them at every level - indeed, the partnership was made up of many of the local stakeholders required. It was demonstrably a real partnership, with the agencies and individuals involved sharing a common purpose and sense of ‘ownership’ of the Project.

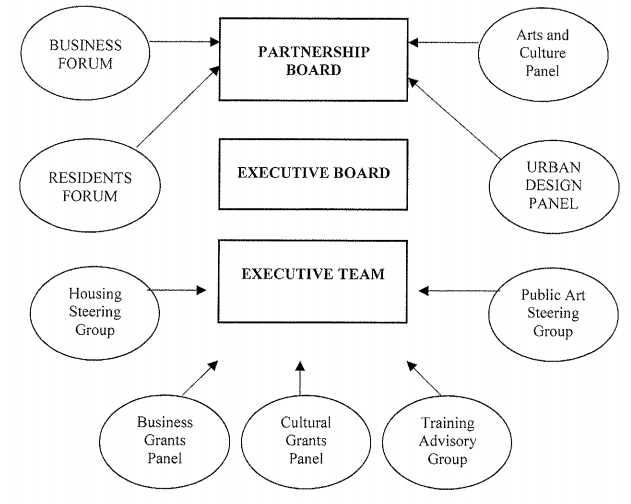

The Partnership was constituted of six council members, six people from other public organisations, six from the private sector and two local residents. Some of the public organisations were members of the English Partnership, which was the National Regeneration Agency before 2008. Notably, relationships between public agencies and the private sector were cultivated with forums and panels feeding in important topics, questions and guidance along the way. We can see this in a table taken from a report on the project, undertaken by Newcastle University in 2002.

Separate forums were created to discuss aspects of the projects in more detail, and these were fed back into the Partnership Board. Importantly both residents and businesses were represented here, allowing both voices to be brought to the discussion. The importance of this was highlighted again by Durham University a year later:

“Business and Residents Forums added another valuable dimension to the process, not least by ensuring that the ‘experts’ on the Partnership heard the everyday, practical concerns of people living and working in the area.” (External Evaluation 2003)

Both evaluations point to the notion that members of the board felt ownership in the project and that this combined feeling of impact and responsibility drove the success of the programme. Much of the success of this regeneration project comes down to the commitment and dedication of the board, over such a long and complicated project.

“Over the past six years, the property market has steadily strengthened, Grainger Town has acquired a very positive reputation and the Partnership’s successes have been acknowledged by awards for good practice and effective regeneration.” (External Evaluation 2003)

Importantly, this project is not a success solely on the virtue of those involved and awards collected; the area rose significantly across many quantified scales:

|

|

TARGET |

ACTUAL (2007) |

|

Jobs created |

1,900 |

2,300 |

|

Training weeks |

5,400 |

5,100 |

|

New businesses |

200 |

330 |

|

New floor-space |

74,000 sq.m |

81,000 sq.m |

|

New dwellings |

520 |

570 |

|

Buildings re-used |

70 |

120 |

|

Public investment |

€59.5m |

€67m |

|

Private investment |

€199m |

€288m |

By 2010, evaluation reports on Grainger Town, also undertaken by Durham University, indicated that enduring quality of public realm works and suggested that the project should focus more on branding the place - communicating the area’s historic identity. The subtext of this is that branding was not a focus of the original project and that only now there has been development, and success, can such branding occur. The original plan focused more on the communication between members of the partnership towards successfully completing the plan, than in communicating an ideal outcome before it was realised.

Despite all this success, since the project board’s dismantling in 2004, the complexities of bringing private investors and public organisations together over smaller heritage regeneration projects, are becoming apparent. But, despite complexity, it is still a rewarding and productive process. The report echoes the ‘Heritage, Place and Identity’ project at the RSA, that it is through a highly integrated processes of communication with all relevant stakeholders, not least the local community, that such heritage led regeneration projects can find economic and social benefits.

A small caveat is that while Grainger Town provides a lot to learn from, we shouldn’t assume that the same process would achieve the same results elsewhere; not least because the project benefited from growth and expansion in the retail and leisure sectors typical of UK city centres before 2008.

The lessons we can take are based on the theme of communication and engagement right from the start (and before if possible): let those with the most at stake be the stakeholders, and navigate the complexity of priority-setting through the dedication of people set on achieving more than an idealised brand.

Ironically, the very danger we must avoid is that Grainger Town - with its well-evidenced impacts - becomes a ‘brand’ of heritage project divorced from the context in which it arose; what Monika Krause calls a ‘good project’, at risk of becoming ubiquitous to the extent that subsequent projects transcend the local grounding which made Grainger successful in the first place:

“The pursuit of the good project shapes the allocation of resources and the kind of activities we see, and it does so relatively independently of beneficiaries’ preferences and needs. Agencies sell projects in a quasi market, in which donors are consumers. The project is a commodity and with that those helped, beneficiaries, become a commodity, marketed to and chosen by donors.” (The Good Project, M. Krause 2014)

Dave Yates – With kind thanks to Thomas Hauschildt

Related articles

-

Blog: I love Dundee

Jamie Cooke

I love Dundee. It’s funny, but even in the world of today where Dundee is vibrant with the development of the V&A and waterfront, its status as a UNESCO City of Design and top place in our very own Heritage Index for Scotland, this is a statement that can be met with a range of responses ranging from ridicule to incredulity, especially in the Central Belt of Scotland.

-

Blog: Heritage for the Future. Join the Debate.

Clare Devaney

In November 2015, the RSA and HLF will co-host Heritage Question Time panel debates in Bristol and Greater Manchester. Join the debate!

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.