The UK’s manufacturing industry is in terminal decline. Our labour costs are too high to fend off emerging economies, and we lack the skills to compete on advanced manufacturing with Germany, the US and others. We are in a rut and there is little we can do to push back against the forces of globalisation.

At least, this is the story we’ve been told for the last decade. But what does the data tell us?

Look at the latest findings from government surveys and it appears that manufacturing is finally turning a corner. The sharp decline in manufacturing output has halted, productivity is growing slowly but surely, and the composition of the sector is tilting towards higher value activities.

Here are 5 reasons to be cheerful.

#1 - Manufacturing output and employment shrank rapidly for many years but now look stable

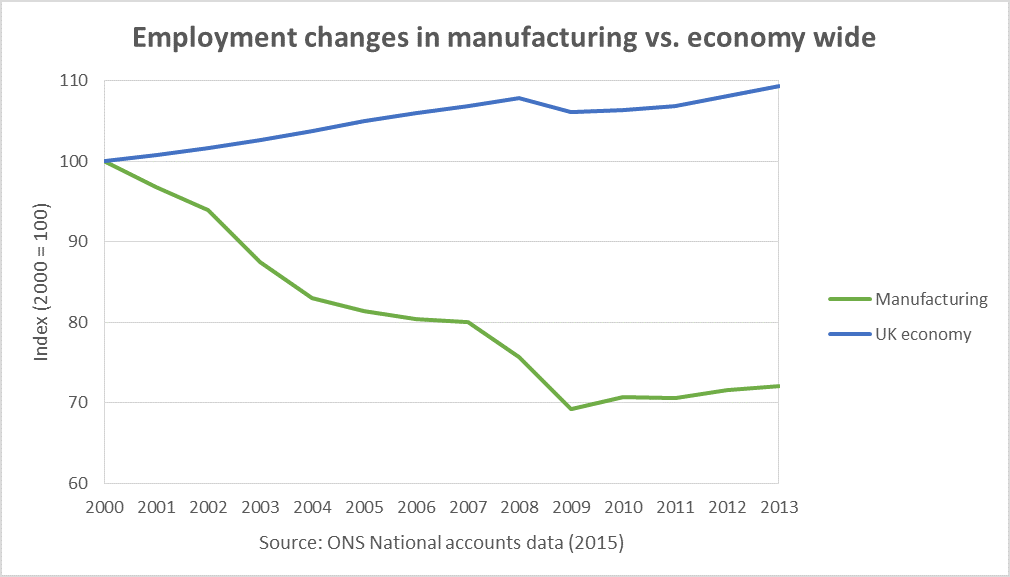

In its heyday just after the Second World War, manufacturing accounted for a third of the UK’s economic output. Today it makes up just 10 percent. Likewise, after a similar fall in employment, only a tenth of the UK’s workforce are now employed in this sector. Yet the atrophy appears to have halted. As the graph below shows, while the manufacturing workforce shrank by a third between 2000 and 2009, the decline has since plateaued. The same is true of output, which has remained stable following the crash of 2008.

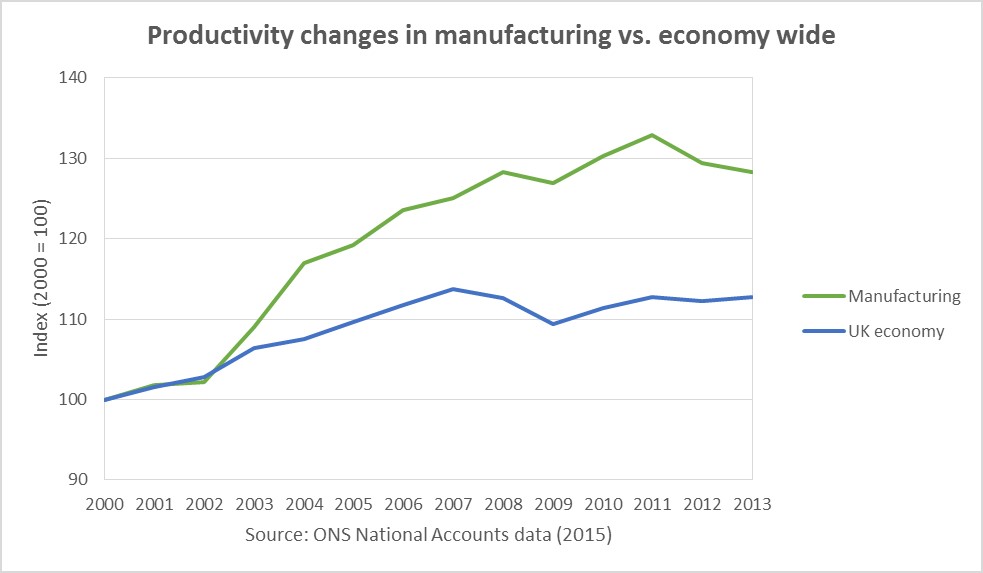

#2 - The productivity growth of manufacturers has outpaced the economy-wide average

The UK’s manufacturing industry has seen a sharper fall in employment than output, which implies a rise in productivity. Output per worker among British manufacturers has grown by nearly a third since the turn of the century, compared with 10 percent in the UK economy as a whole. The government’s Business Population Estimates show that output per person in manufacturing firms averages £214,000, compared to an economy-wide average of £140,000. This in turn is reflected in the wages of factory workers. Manufacturing employees earn around 20 percent more than their counterparts in the service sector.

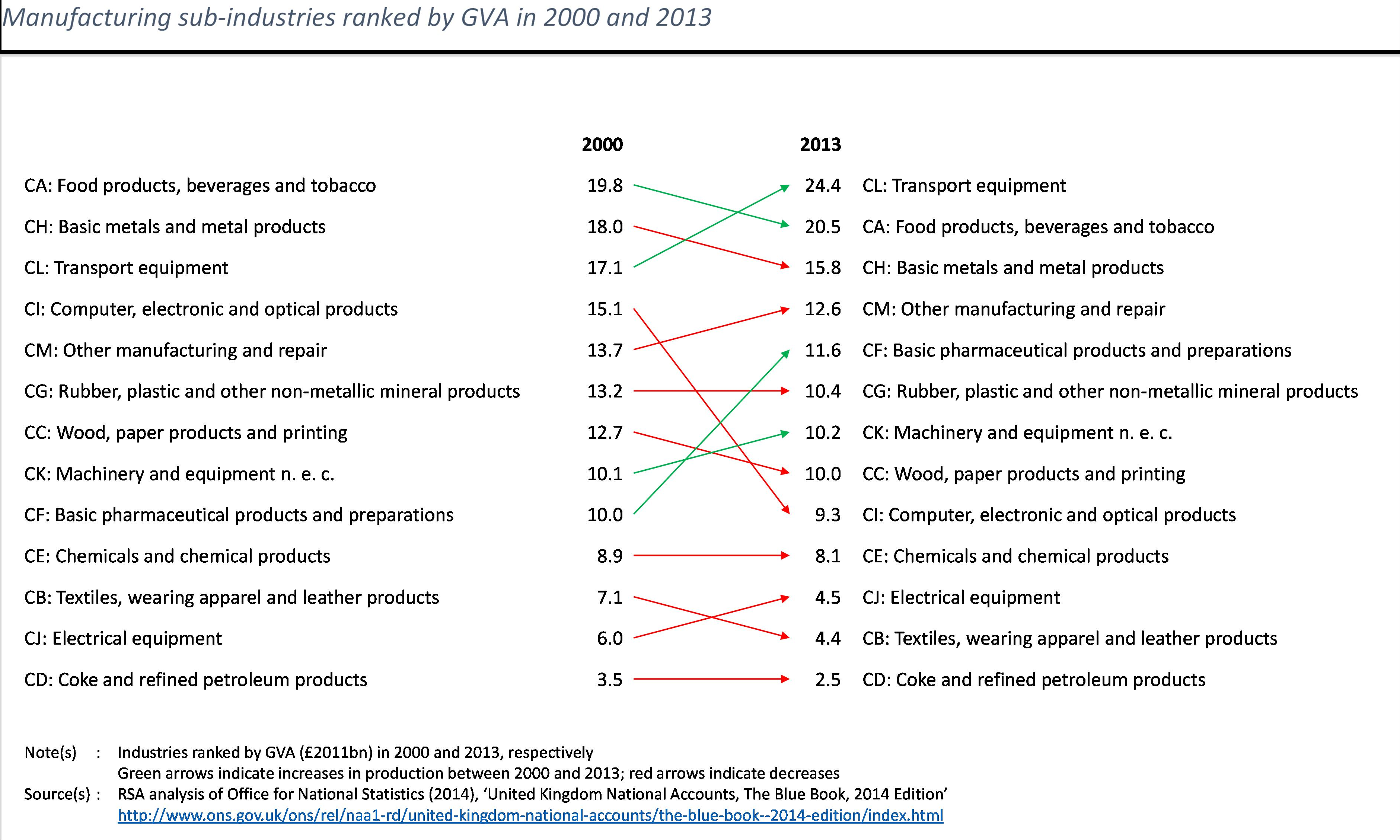

#3 - The composition of UK manufacturing is tilting toward higher value activities – textiles are down and transport is up

Manufacturing encompasses a wide range of activities – from the mining of raw materials, to the production of automobiles to the creation of chemicals. Most of these subsectors saw a reduction in their GVA over the course of the last decade. The most drastic falls were in textiles and computing – both of which have shrank by around 40%. But three subsectors are bucking the trend of decline: transport equipment, pharmaceuticals and food products – all of which tend to create higher value products. Makers of transport equipment are three times as productive as makers of textiles. Ergo, this change in sectoral composition may be a good thing for the UK economy.

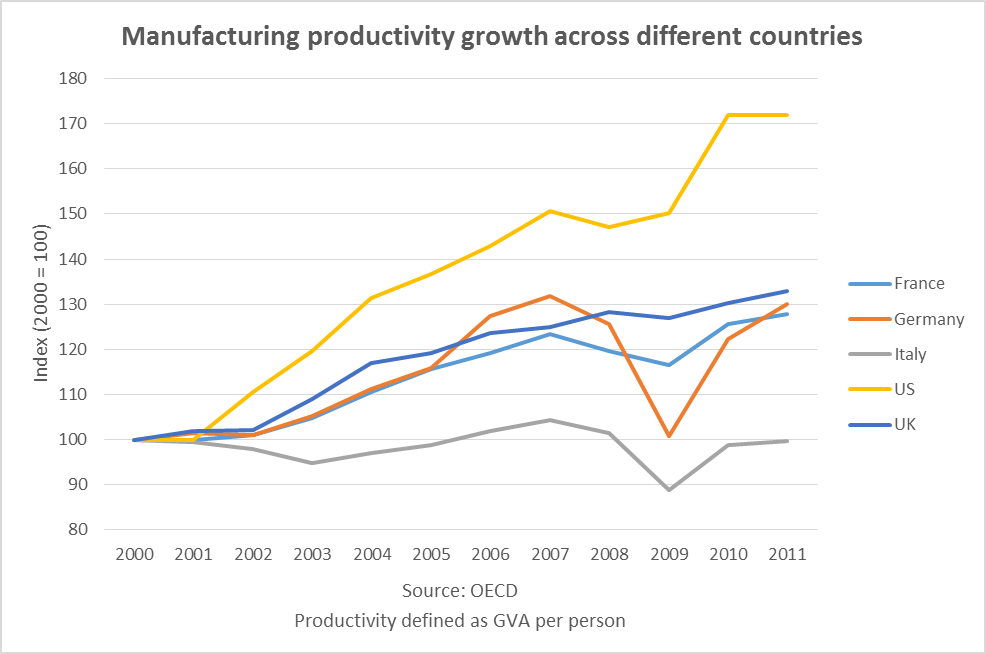

#4 - Our manufacturing industry is outsized by international competitors, but not necessarily outgunned

On the surface, the UK’s manufacturing base pales in comparison to those of other advanced economies. While manufacturing accounts for 10 percent of GVA in the UK, the figure is 12 percent in France, 17 percent in Italy and 22 percent in Germany. Yet our industry is boosting efficiency at a faster rate. OECD data shows that UK productivity grew by 33 percent between 2000 and 2011, somewhat higher than that of the aforementioned countries. Of all the nations, the US is the country to beat, with a productivity rise of 72 percent over this period.

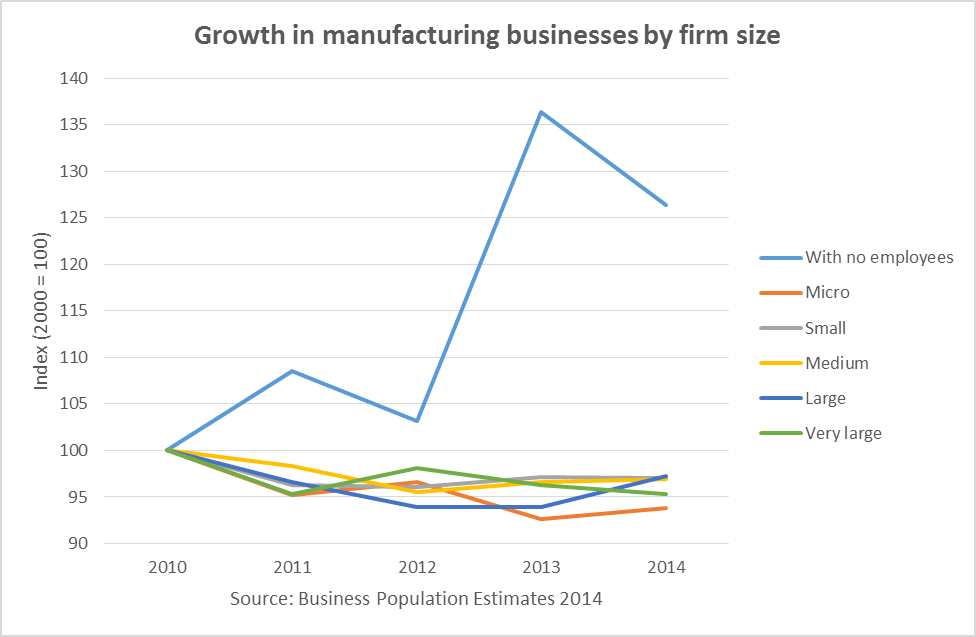

#5 - One-person makers are becoming more prominent

The term manufacturing conjures up images of enormous factories churning out millions of products on a model of mass production. But one of the most interesting trends in recent years has been the growth of manufacturing businesses with zero employees. The number of ‘one-person makers’ has expanded by a quarter over the past five years, compared with a decrease in the populations of all other firm sizes. Many of these are not turning over a great deal, and are likely to be part of the growing army of hobby tinkerers. But individual makers who are registered for VAT are nearly just as efficient as small businesses, suggesting that new technologies have made it more viable to do manufacturing on a micro scale.

So there you have it. We may not be the workshop of the world anymore, and the days when industry would employ thousands in vast factories are likely to be long gone. But one thing is clear: reports of manufacturing’s demise are greatly exaggerated.

If you're interested in all of this, keep a look out for a new RSA study exploring the potential implications of a growing number of makerspaces across the UK.

Follow me on Twitter here.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Thanks Nick.

A great point, and one I came across before when reading Ha Joon Chang's book, '23 Things They Don't Tell You About Capitalism'. I believe he cites a couple of studies that have attempted to calculate the impact of outsourcing on the size of the UK's manufacturing industry.

Worth a read if you haven't already seen it:

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/oct/25/things-tell-capitalism-hajoon-chang

Thanks Benedict, some interesting data. Firstly, a confession we publish The Manufacturer magazine so we have big vested interest (www.themanufacturer.com).

I could make a whole range of comments but I will focus on one. The data comparison between the scale of manufacturing in the immediate post war period (in fact up until around 1980) and the current day is much quoted but is hugely and fundamentally flawed. Prior to 1980 the idea of having a third party handle your factory catering, cleaning, security, logistics, haulage, IT (I could go on) was simply unheard of. Manufacturers are now highly efficient and have outsourced huge parts of their operations to Initial, Compass, DHL etc. The effect is stark but hugely overstates any decline in the value of manufacturing to the overall level of UK GDP.

The growth in the service sector has largely come off the back of manufacturing and the mistake of all previous Governments has been to recognise the service sector growth as something that has occurred instead of manufacturing and not (as is the reality) because of manufacturing.

Nick Hussey