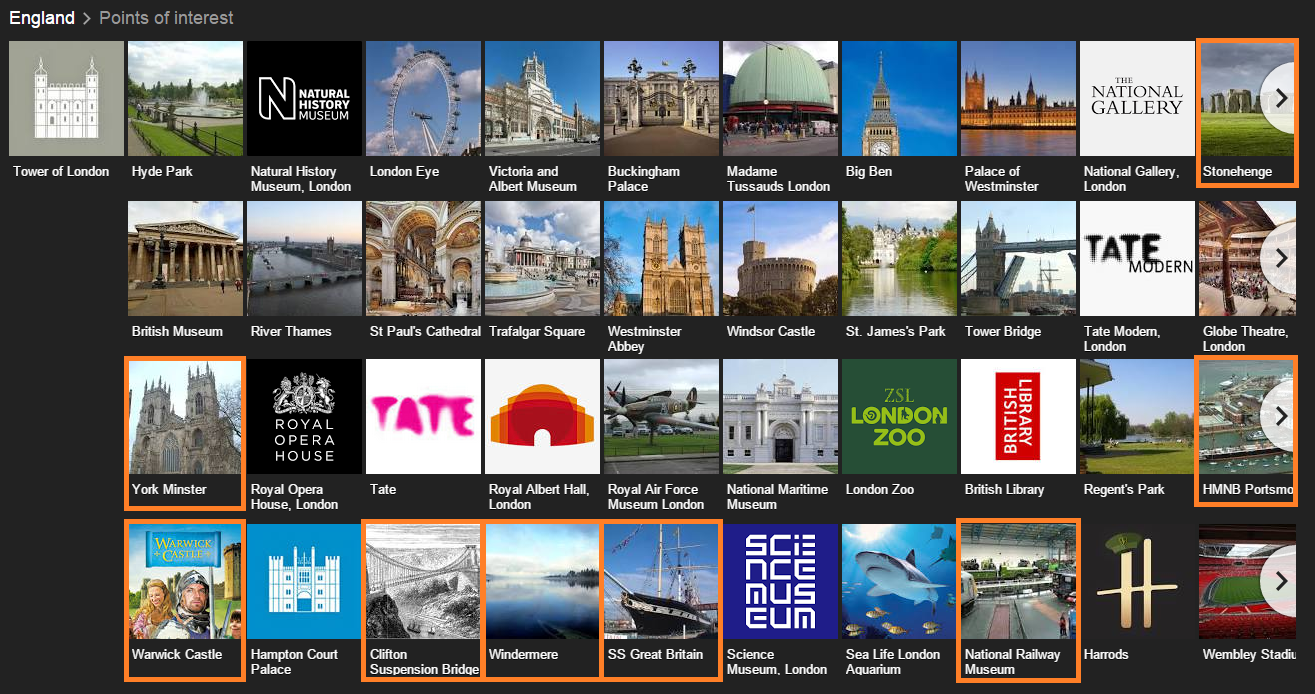

Googling for “Visit England” you will quickly find results listing impressive buildings, monuments and archaeological sites, and places of natural beauty. But there is more to heritage than famous architecture and natural beauty.

Architecture can instil a strong sense of nationhood, connecting the past with the present and future of a nation. Buildings and public spaces come to symbolise chapters in a country’s history, witnessing times of joy and suffering alike. They have been there before us and are likely to remain after we have gone. Thus, the spiritual and emotional value of tangible heritage is often significant, deserving special protection and conservation.

But there is more to heritage than famous architecture and natural beauty. Whilst the World Heritage Convention, focusing on tangible heritage, has been widely adopted, intangible heritage receives less attention. But knowledge and skills passed from generation to generation, including arts, traditional crafts and cuisine form an essential part of our heritage – a part of who we are. The UK has not ratified the UNESCO convention on intangible heritage, despite its world-leading cultural vitality in areas like dance music, with venues currently under threat from forces of urban development.

The search result above focusing on tangible heritage does not come as a surprise. The internet allows us to visit places with our eyes before our bodies and therefore tangible heritage might receive more attention and is considered as being of higher value. The experience of something intangible like the smell of a market or the taste of unfamiliar food is lost online.

However, just like tangible heritage, these practices connect the past with the present and future and provide significant emotional value. This becomes particularly evident when groups are being neglected, marginalised and denied equal right to exercise their culture. All too often this leads to division and conflict. Respecting intangible heritage enables us to understand other cultures better than merely visiting their tangible heritage on a holiday. Thus, intangible cultural heritage carries with it a social value that helps us to foster intercultural relationships.

As opposed to physical heritage, intangible heritage is not bound to places, but embedded in individuals and can therefore be shared across cultural boundaries and between places. Just as tangible heritage can be commercialised intangible heritage lends itself to generating economic value as well. The choice of international cuisine in British cities and the success story of curry dishes in particular is a prime example of how intangible cultural heritage from other regions can shape our own identity and generate economic benefits alike.

Other examples include traditional dances and festivals attracting tourists. Chinese New Year Celebrations and the Oktoberfest are now celebrated around the world, effectively an ‘export’ offering enrichment and commercial opportunity.

However, the flexibility of intangible cultural heritage also leads to fragility. Tangible heritage can be preserved by a small group of people or organisations with the required skills set and funding. Intangible customs, however, depend on individuals voluntarily transferring skills and customs to the next generation, often in an informal community or family based setting. But the relevance of practises exercised in the past in today’s world cannot be taken for granted. Thus, rather than protecting the current form of intangible heritage we need to allow for it to adapt to a new context to make it relevant for today’s societies. Intangible heritage is not fixed, it is fluid.

To emphasise the importance and potential of tangible and intangible heritage alike, the RSA has teamed up with the Heritage Lottery Fund to develop an online Heritage Index. It identifies tangible and intangible heritage assets, and will enable each council area to use them more creatively in developing their broader social and economic strategies. The index goes live on 23 September, so watch this space; and let us know how useful it proves to be in highlighting, protecting and taking forward the ‘cultures and memoires’ of the places in which we live.

You can follow the team @RSA_PSC

Heritage,Identity and Place project

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

This is a really interesting and important article, Thomas. The fact that Britain has not signed up to the Treaty and so would be required to support intangible heritage means that those of us working in heritage crafts are really struggling. Research funded by the Dept for Business, Innovation and Skills – Mapping Heritage Craft (2012) – revealed that for England alone heritage crafts have a turnover of £10.8 billion and a GVA of £4.4 billion, with almost 210,000 practitioners. This is economically significant! 78% of these craftspeople are self-employed and 77% are not passing on skills because of the challenges of funding when working on your own (If you give up the equivalent of a day a week to train, then your production goes down by 20% and that's your profit margin; the government expect you to pay an apprentice even though in crafts that apprentice is rarely useful until towards the end of their training). The workforce is also ageing.

The Heritage Crafts Association was set up as an umbrella group for these crafts, which are such an important part of our heritage (just think of our surnames – Barker, Tanner, Potter, Skinner, Weaver, Turner and, of course Smith), and we have made significant progress, including the annual Heritage Craft Awards of bursaries and financial recognition of excellence (up to £24,000 available). However, we cannot get funding to support what we do. Contemporary crafts are funded through the Arts Council and the Crafts Council, but neither recognise traditional skills, so those working in these areas cannot apply for any grants from the Arts Council, unless they work in a museum, as the Council does fund museums! We are working to identify crafts which are close to extinction and will try to get them publicity, but without the funds to pay staff to do the work it is a real challenge. The endangered crafts are most often viable, and thriving businesses. One of the last folding pocket knife makers stopped on August 17th this year with a 6-month waiting list in his order book. The last scissors makers (including Eric the putter-togetherer, yes genuine job description) are in their 70s. We lost the last hand-made sieve maker two years ago, and there is a demand for these. People now want wooden ladders as they have a 50 year life and the last ones were made that number of years ago, but there is no-one making them full time as a business. The last Master Cooper is looking for an apprentice. The stories are out there but our team of volunteer Trustees with one part-time administrator struggles to get heritage crafts the support and attention they deserve. Is there anything that the RSA can do?

Patricia, thanks for these insights. I have read Mapping Heritage Craft, and include a reference to this same data in our upcoming report.

I am a big fan of Richard Sennett who wrote about the broader relevance of 'craftsman-like' thinking: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/06/books/review/Hyde-t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0. I've done research on the remarkable cluster of craft businesses around Hatton Garden, for which some protections have been secured via Camden Council's Section 106 agreeements.

If helpful, I will ask my colleague Joanna Massie to see if we can at least connect you to others in the RSA Fellowship who may share your passion. You would also be welcome to further develop a call for action and publish here on our website, via RSA Comment.

In the meantime I wonder what your main 'ask' would be to support traditional craft skills? and whether schools would be of relevance? (http://www.policy-uk.com/event/1766/The_Future_of_Art__Craft_and_Design_in_Schools__Next_steps_for_cultural_education)

I fully agree with the importance of intangible heritage and welcome the RSA's move. I've seen how many cities in Europe are using the UNESCO label to develop a sense of well-being in their communities as well as using it for tourist promotion. My one concern is that I hope the RSA and the Heritage Lottery Fund are not setting up a system for the UK using it as a excuse not to join the global UNESCO List under the Convention. I hope the RSA will use this UK List primarily as a step in a campaign to change DCMS's view so that the UK will ratify and join the UNESCO List of intangible heritage as well as being a member (and an active one) for the UNESCO World Heritage List of tangible heritage.

We haven't got a view, yet, on advocating the UK ratifying the UNESCO intangible treaty, but 'living history' is a big passion of mine. In particular, I like the example of contemporary dance music and club/rave culture. Its something the UK has pioneered for decades, and draws people from around the world to participate. Its as concerned with staying 'up to date' as revelling in its own rich heritage, back to Northern Soul and Rock and Roll. Its an inclusive part of modern society, not facing the struggles of our flagship heritage institutions to attract the young, poor and those from ethnic minorities. And yet mostly venues and event organisers are businesses, not charities...and would never consider themselves part of the heritage sector.

I think there are many things that could be done to support such heritage, beyond any role for UNESCO.

FYI, Dundee - one of our case study cities - is a UNESCO 'City of Design'.