Arturo Soto was born in Antofagasta, northern Chile. For those who benefit from the riches of its mining industry, Antofagasta is a wealthy city where GDP per capita is similar to the UK. For those who don’t benefit, Antofagasta is home to substance abuse, drugs trafficking, crime and domestic violence for many of its poorest residents. As Arturo explained to me, at some point this gaping social divide stops young people from following their dreams.

Arturo had left home at just 13 and lived in an abandoned house in the favelas, alone. But soon he decided he needed to pursue his dream of a better life. His escape was the beauty and the power of the ocean. He began bodyboarding and then teaching other children, an activity that has grown into a business; a humble wooden hut brings in children from all backgrounds and inspires them with the stillness of nature, yoga, philosophy classes on the beach and a belief in the power of following our dreams.

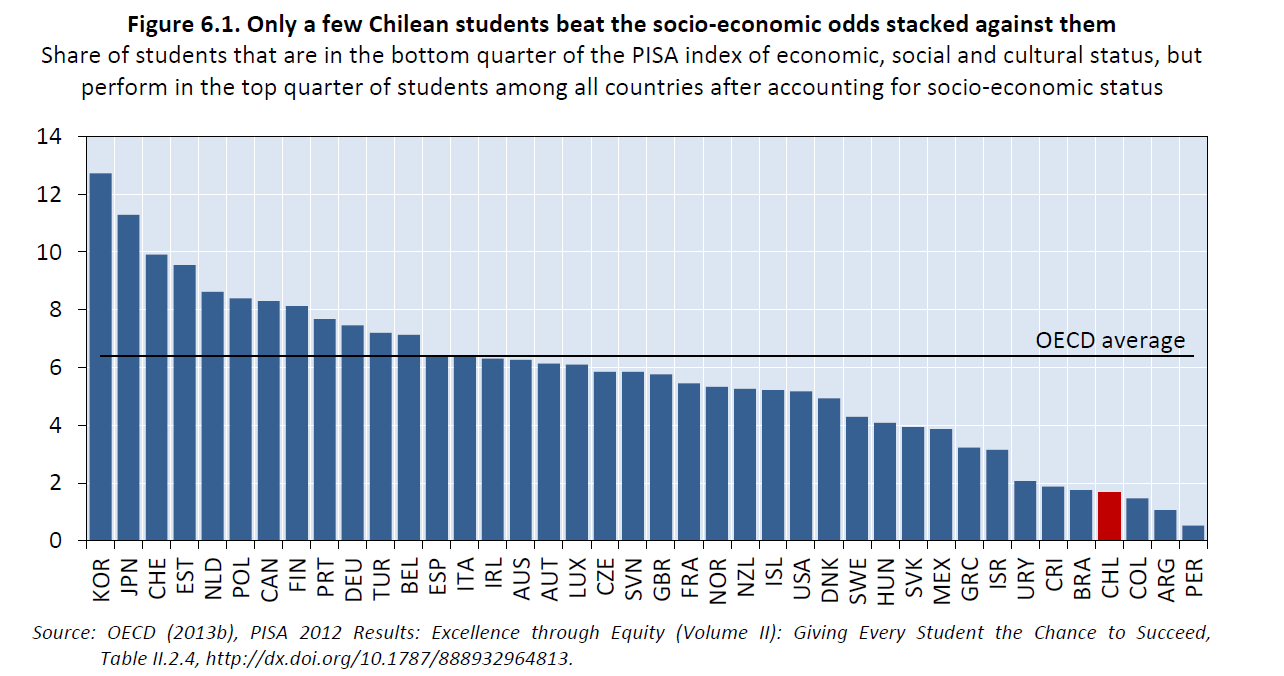

In Chile, Arturo’s story is a rare exception. OECD analysis of PISA data shows that young people in Chile are amongst the least likely to defy their socio-economic odds in terms of education attainment.

Source: OECD, ‘Chile: Policy Priorities for Stronger and More Equitable Growth’, September 2015 (OECD ‘Better Policies’ Series)

I’d met Arturo on the bus from my hotel to the second day of FIIS 2015, Chile’s International Festival of Social Innovation in Santiago. I had been asked to talk about social innovation as a tool for inclusion and referred back to Arturo’s story of his beating the odds. But I also challenged the UK’s track record. Look closely at the graph above and you’ll see we don’t hit the OECD average (even if that is skewed by particularly strong performers in South Korea and Japan).

This led me to consider the concept of inclusion and I urged that we look beyond headline economic measures of labour market participation or Gini co-efficients. Chile has, for example, a lower level of unemployment than the EU and OECD, but this disguises low levels of female participation and deeper gender inequalities. Similarly, health inequalities are a key indicator of social inclusion and have profound economic knock-on effects. Finally, it is important to consider the political realm and degree to which all the above factors contribute to inclusion, or equality of citizenship. What voice do I have from the favelas? What incentive do I have to engage in debate that seems wholly disconnected from the reality of how I live, work, or care for my children or elderly parents? How can government design effective economic and social policy if it is not open to understanding and responsive to this reality?

Only last week the President of Chile, Michelle Bachelet, announced a process to draw up a new constitution for the country. Electoral reform has already begun with the repeal of the unique binomial system, a very limited form of proportional representation which concentrates power amongst party leaders, who “virtually choose the winners when they make up their lists”; “With no real competition in many districts, the elections hold little interest for the voters…” (Huneeus, 2006). At FIIS I was due to join a panel debate on ‘liquid democracy’ and whether this electoral approach – which allows people to transfer their vote to a trusted friend, colleague or other associate – might, enabled by technology, help build trust and reconnect citizens.

Unfortunately illness has meant that I’ve lost my voice and can’t speak to order a coffee, let alone debate on the illustrious FIIS stage. If I had been able to, here are the three main points I would have made. First, that party factionalism and realpolitik could have an even tighter a grip on determining the result than under the principle of one (wo)man, one vote. Person A might trust person B enough to transfer their vote, but Person B is then able to transfer both votes to Person C, and so on…increasing the opportunity for implicit or explicit corruption. Second, liquid democracy will only be as good as the depth and breadth of the debate surrounding particular issues. Online voting, even amongst the more interested or more informed (so the theory of liquid democracy goes), provides no qualitative advantage in itself. In fact, you only have to look at the ‘most read’ columns of online news outlets or some of YouTube’s greatest hits to see that what is popular online is not necessarily of higher quality.

Work by Paul Ormerod and others (2012) has shown there is no correlation between product quality and its online popularity, and that we confuse the two when we start to believe that – and act as if – popularity is a signal of superiority. Finally, women had to chain themselves to railings and endure force feeding in prison for me to have the right to vote; I’m not transferring mine to anyone.

I continue to argue that lack of political connectivity is our ticking time-bomb. Even without a recent history as complex as Chile’s, the UK needs to seize the opportunity of place-based leadership to give citizens a genuine voice in the future of their towns, cities and county regions. The Labour Party has recognised this quiet yearning for a ‘new politics’ and as well as crowd sourcing PMQs on Twitter, it hopes to “explore how politicians could be made to work for everyone in Britain” through citizens assemblies. As Claudia Chwalisz of Policy Network suggests, if these amount to “merely a widescale consultation” without structural change then “disappointment surely looms”. We need to restore political connectivity and build a genuine link between people and their systems of governance. Only then can we enable the voices of citizens to be heard and valued in decision making. Without this, greater social and economic inclusion will be at worst out of reach, and at best only half a job done.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Two comments. First, Fig 6.1 would benefit from some elucidation. It shows an intriguing range of countries operating below the average, raising questions as to why this should be so.

Second, Jonathan Freedland's 'Bring Home the Revolution" offers interesting ideas about how lessons from the American political system might be used to revitalise democracy in this country. I seem to recall that such a move would not be without pitfalls but the nub of what he says might be worth a renewed debate.