“Please keep this simple equation in mind: Quality of investment today, equals quality of the global energy system tomorrow, equals quality of life forever.” - Christiana Figueres

- Read our new report 'Money Talks - divest invest and the battle for climate realism'.

I woke up this morning to find my normally cheerful mother-in-law Vatsala looking distressed. Chennai in South India has been flooded, with rivers rushing through familiar streets, ubiquitous power cuts and rising fatalities. Amma grew up in the city and her brother Sreeder called around 6.30am in London to assure her that their mother and wider family were ok, but he also said that there was no sign of the floods abating and the city was in chaos. A BBC news report quotes a police officer saying: "The police want to help but there are no boats. We are trying not to panic".

Does climate change directly cause such floods? The answer to that question is usually a resolute yes masquerading as a qualified no. Climate change doesn’t cause things that directly, but it makes such weather events significantly more likely to happen and more harmful in their impacts. To bring the issue even closer to home, a recent Met Office study suggests the floods that hit British towns and cities in 2013/14 was seven times more probable because of existing global warming. In the context of last night’s vote to extend airstrikes to Syria, it is also worth knowing that existing problems in that part of the world may have been significantly compounded by water shortages related to climate change.

Political leaders have noticed, and the take home messages of the Paris Global Climate Summit will inevitably be ‘progress is possible’. However, it will also be ‘we could do better’ and ‘we need to keep at it’. In this context, the importance of the distinction between merely ‘reducing emissions’, and reducing emissions enough, quickly enough, can hardly be overstated. The cultural question of what is ‘realistic’ has become the preeminent climate battleground.

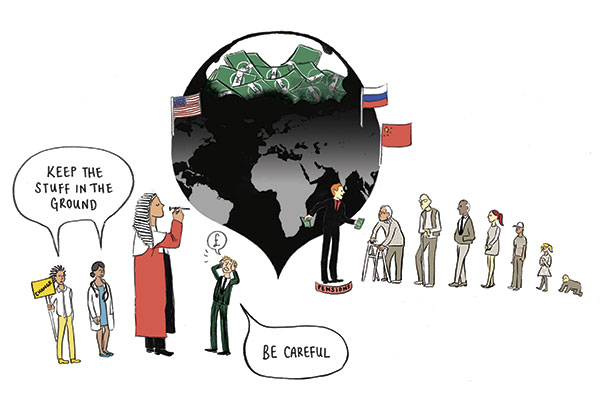

Today the RSA launches a new report: Money Talks: Divest Invest and the battle for climate realism. The report examines the claim that if you want to limit planetary warming to levels deemed acceptable, the beginning of the end of the fossil fuel industry has to be accelerated. The corollary of this realisation is that – for moral and financial reasons- investment in fossil fuels should end, which entails divesting (dis-investing) in coal, gas and oil and re-investing in alternative energy, particularly renewable energy, storage and transportation.

There are four main turns in the argument:

1. The unassailable logic: minimising climate risk is about doing whatever it takes to keep fossil fuels in the ground.

2. The unbelievable challenge: we are deeply dependent on fossil fuels and the requisite speed and scale of decarbonisation is hard to imagine.

3. The signal that sets the agenda: the ‘Divest Invest’ movement is needed to strengthen resolve and quicken the pace of the transition.

4. The map that yields momentum: the seven dimensions of climate change perspective (science, law, technology, money, democracy, culture, behaviour) gives us hope, by illustrating how the positive impact of acting in one dimension can have an important knock on effect on the others.

At a cultural level divestment stigmatizes the continued investment in fossil fuels, attempting to remove their social license to operate. At a technological and monetary level it signals to financiers that we are at the beginning of the end of the fossil fuel era, encouraging them to redirect their money towards new forms of research and infrastructure. At a democratic level, divestment challenges the political power of the fossil fuel industry as it manifests in subsidies. At a behavioural level, divestment wakes people up to their unwitting financial complicity in the challenge, and gives them a way of acting that feels commensurate with the global and systemic nature of the problem.

And all of these factors influence the regulatory ambience or ‘surround sound’ in which legal principles are considered and laws are made; a factor that will continue to be crucially important after the Paris talks.

We need to focus. Global warming is already here. We can’t ‘stop it’ as such, but anybody who thought we could failed to grasp that it’s not a tornado on the horizon that can be hidden under the bed, but rather a steady accumulation of greenhouses gases that that linger with intent and loom ever larger in the atmosphere; that’s been going on for several decades and we need to stop it.

You may not think of yourself as an investor, but you can and do influence how investments are made. In their lucid and intricate overview of the global climate challenge 'The Burning Question', Duncan Clark and Mike Berners-Lee state the striking fact:

“Almost anyone with a financial stake in global society is a part-owner of a fossil fuel reserve.”

The point of campaigning for charities, churches, universities, foundations, private and public sector organisations and individuals to significantly reduce or withdraw existing investments (including pensions) in coal, oil or gas companies is not to put fossil fuel companies out of business in the short term, but to draw attention to the lack of viability of their business model and undermine their social licence to operate and political power in the short term, so that they disappear or transform their energy portfolios in the medium term rather than the long-term. Divest-invest is fundamentally about speeding things up, and the science of climate change tells us that timing really matters – we can’t afford to get locked in to more decades of fossil fuel infrastructure.

Finally, the report can be summed up in a short exchange that needs a little context to understand. In June 2015, the RSA hosted ‘a climate constellation’ workshop under the Chatham House Rule, with a range of experts in the climate change field including NGO strategists, Climate communication experts, climate change funding bodies, climate journalists and academics. The constellation approach is conventionally applied to family therapy, but is often used in organisational change processes. This was therefore an innovative attempt to allow people who have been working on climate change for several years through the same modalities of speech, text and evidence, to examine the issue from a more intuitive, somatic and emergent perspective. The feedback was extremely positive and the moment quoted stemmed from an inquiry where the question of divesting from fossil fuels was ‘constellated’ with about eight people representing different aspects of the issue; they established spatial relationships and the experienced constellator helped to tease out what these different aspect of the problem were feeling in those relationships, in the given instance through questions. For those in the room, the following moment was electric:

Constellator: Say: I am evil.

Fossil Fuel: I am evil.

Constellator: How did that feel?

Fossil Fuel: Bollocks.

Constellator: OK, say: I am the past.

Fossil Fuel: I am the past.

Constellator: How did that feel?

Fossil Fuel: Better, about right.

You don’t have to think of fossil fuel companies as the enemy. The abundant prosperity they have brought us shouldn’t be taken for granted, but we need to transform now. The money that drives technological change effectively means this: 18th century coal will make 21st century solar and wind possible. We need fossil fuels in the short term, we really do. But we need not to need them in the near medium term – even more. And the shorter the short-term, the better.

- Read our new report 'Money Talks - divest invest and the battle for climate realism'.

Dr Jonathan Rowson is Director of the Social Brain Centre at the RSA and the author of Money Talks: Divest Invest and the battle for climate realism, published today.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.