We have arrived at a critical moment for design thinking. As management consultancies snap up service design agencies at record pace and business schools around the world offer design thinking courses, workshops and lessons in empathy for their students, ‘design thinking’ is now at the forefront of much business and innovation vocabulary. At the same time, design labs are popping up in state and national governments around the world in an effort to bring an agile, iterative approach to policy making.

And yet, as more and more businesses, governments and institutions describe themselves as ‘design-led’ ‘design thinking’ is in danger of being devalued. Too much of what is practiced under the name of design thinking seems to comprise little more than running structured workshops. The process can now sound technocratic and can feel meaningless. We are now faced with real questions about design’s preparedness to tackle complex issues and the capacity of design methods to deliver scalable solutions. This is a shame as design thinking was borne from a desire to share the creative process more widely.

Established design champions Tim Brown, Roger Martin and Bruce Nussbaum have all written widely on this topic as well, citing the many botched experiments in design thinking in businesses around the world. Too often, even with the best intentions, design thinking has been adopted too quickly and without a real appetite for the messiness, circularity and long (and sometimes drawn out) timeline that successful design process really requires. As Brown and Martin wrote recently in Harvard Business Review, we also now find that many people identify as design thinkers without the real skills to deliver effective innovation.

Generally speaking, design thinking can be defined as the formal method for the practical, creative resolution of problems and the realisation of solutions, with a focus on the ‘user’ or ‘human’. ‘Design thinking’ initially referred to specific cognitive activities that designers apply during the process of creation, but now it has come to mean key features of a creative process.

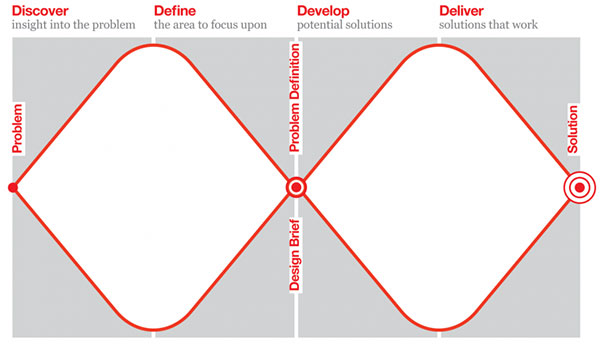

There are many descriptions of the design thinking process, but one of the most widely accepted is the Double Diamond (developed by The Design Council):

In the first stage design thinking refers to a process where a problem is identified and explored and then insights are discovered to arrive at a more specific problem definition, which then results in a design brief. In the second stage a range of solutions are developed and prototyped before a final solution is delivered.

At the RSA, we work towards a mission to foster ‘the power to create,’ and with this goal in mind, design thinking can be a very powerful tool. We see it as vital that people and communities understand how they can unleash their creativity. The creative process is a mysterious one, but breaking it down through the application of design thinking can make it more tangible and straightforward, allowing more people to unleash their own creativity and help others to do the same. Design can help us to be more aspirational for ourselves and our solutions.

We are committed to embedding design thinking throughout our work at the RSA. But we also want it applied rigorously and with a focus on the realisation of solutions. We believe the design thinking is only valid when the whole process is followed through; in a recent conversation with the service design agency LiveWork, the team said that ‘a little design was better than no design.’ Perhaps, but it is important that ‘a little design’ still means a lateral slice of the whole process rather than stopping short of prototyping or delivery (as noted above, running workshops doesn’t equate to a design thinking methodology).

Our work now seeks to reassert a demanding concept and practice of design thinking approach. To date, we’ve identified 4 key criteria that design thinking practitioners should (re)adhere to:

- Commitment to the whole process:design processes are highly iterative, they are for the whole journey of an idea from conception through to implementation. The journey is extremely important for stakeholders and significant transformation can be achieved through the process, but it must be followed through from problem definition through to solution delivery.

- Genuine engagement with ‘humans/users’: authentic engagement and consultation with users means taking the time to listen with a commitment to active participation and applying user insights to deliver the best possible solution. Using observation and ethnography can help us understand what people do but we need also to hear what they think. Authentic engagement also means thinking about who is part of the process. Who are the ‘users’ to engage with? What do they bring to the process – what insights and understanding, but also what experiences and biases?

- Human understanding and craft: in the same way that traditional designers have a deep understanding of materials (wood, metal, plastic, computer programmes, etc.) and how they can manipulate these through craft to create delightful products and outcomes, service designers must have a deep understanding of people and organisations – the kind of insights offered by behavioural economics, social psychology, group dynamics, organisational change and systems thinking – if they are to maximize their chance of developing ideas that work.

- Reassertion of design aesthetics: design thinking gained traction initially because a successful design process achieves elegance, sensorial acceptance and emotional appeal for the solution (be it a product, service or campaign); in a new era for design thinking, we must reassert the value of the aesthetics of design that go beyond traditional technocratic and top-down solutions. Aesthetics are not only about the form of the outcome, but about the attitude, the process and the ‘why’ of a particular solution.

Design heritage, skills and thinking are and have always been a strategic asset for the RSA, demonstrated most explicitly through our established RSA Student Design Awards programme. The RSA now seeks to understand how we can champion a new era for design thinking that defines good design approaches in a more thorough way and brings about the new radical ‘Design Thinking 2.0.’ What does it mean to be a ‘Designer 2.0’ or a ‘Design-Led Organisation 2.0’?

Watch this space and join the debate as we seek to develop and refine these criteria and seek a radical future for design…

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

The difficulty with Design Thinking is less with the "design" part than it is with "thinking". The Anglo-American management worldview is overwhelmingly Cartesian. Thinking is seen as a conscious, deliberate activity involving analysis and the development of general, context-free rules and principles that are then "applied" to practice. The principles turn out to be good intentions and desirable outcomes. Hard to disagree with but impossible to apply because of their abstraction from context.They use what Gilbert Ryle would have called "achievement verbs" like "discover", "design", "develop" and "deliver" i.e. they sound like action but are really achievements.

If, on the other hand, we assume that people are rational in an ecological way and have embodied minds (all for good evolutionary reasons) then we can "think" about the world in just as many ways as we experience it. This puts design into a completely different context. The Cartesian worldview isn't "wrong", just incomplete, overused and misapplied. See http://bit.ly/252ss8y

Sevra,

Hi, great post. I'm also interested in the value of user to user engagement. When we look to parallel industries and experiences for design inspiration, I'm mindful that we often do this as part of an observed comparison process; often deeper value can be driven from user to user engagement in the development of transferable learning, prototyping and solution development.

Best wishes, Anita

Excellent article. I particularly like the 'Human understanding and craft' element. This resonates with my own attempt to blend design with the application of disciplined thinking in crime prevention, whether in getting designers to 'think thief' or crime prevention practitioners in the police etc to 'draw on design' - the full process not just the product. This is articulated in my 'Security Function Framework' (Purpose, Niche, Mechanism, Technicality), see www.ucl.ac.uk/jdi/events/crime-science-conf/tabbed-box-2011/ekblom-website.pdf. The framework in fact originated in my experiences in judging RSA Student Design Award entries!

Hi Paul - thank you for your comment. I know your work well on design and crime prevention and am delighted that you've read the blog. Thank you also for your link to your framework - will have a look right now! Look forward to connecting more soon and to continuing the discussion.

Is there an integrated worldwide program under your direction for the Student Design Awards?

Why is the US SDA program apparently separated? Pleas explain.

Thank you for your comment. The RSA Student Design Awards is a global programme and open to students anywhere in the world - more information on the programme can be found here: http://sda.thersa.org/

There was a US-specific SDA programme for a few years, but this now falls under the umbrella of the global programme. Last year, we received entries from 30 countries around the world. Do let me know if you would like to know more and thank you for your interest.

Good article. Like the emphasis on 'whole journey' - you haven't designed if you've only thought.

Thank you, Simon. This emphasis on the 'whole journey' is perhaps most important in all of this and I hope to think and write more about this.