The RSA was asked to present evidence to the BIS Select Committee last week as part of the government’s inquiry into the digital economy. We were specifically invited to reflect on our work on the sharing economy and expand on the report we released earlier this year about how the sector has evolved to date.

Here are five key takeaways from the session for government:

1. While we are confident the sector is growing quickly, we still lack the data to definitively conclude by how much and in what ways.

The economist Diane Coyle noted in this session that we have little idea how the sharing economy is changing the way that people are working, how many people are working in new ways, and how many microbusinesses there are in the sector. The complexity of the market will be difficult to capture in measurable ways, but it is important for the government to make sense of (how the market functions underpins the framework of government policy; changes to the market may mean that the framework is not fit for purpose).

At present, Coyle explained we have a system that is based on large companies delivering services and administration to people that are thought to be working in a conventional job for a number of years. However, the growth of smaller businesses, digital start-ups and the sharing economy suggests that many people no longer work in this way. If these changes are significant, it will require rethinking how our tax and benefit systems work for example (as the RSA is also doing by exploring Basic Income as an option).

2. A clear strategy for growing the sharing economy must recognise that the sector’s activities are diverse and ever-widening in scope, so challenges will vary depending on the nature of the activity.

The sharing economy is a socio-economic system that encompasses local, grassroots-funded initiatives, such as time banks and tool libraries, as well as global, venture-backed companies – i.e. the Airbnbs and Ubers of the world. It may seem impossibly broad, but keep in mind that when Airbnb and Uber were first fledgling start-ups they were recognised more for their social potential than their economic prowess. As the RSA has mentioned, the shunning of these companies has been a gradual development, intensifying with scale.

Size plays a role in determining the challenge. Small, locally-bound initiatives will encounter barriers to attracting funding and sustaining free or low-cost models. Global platforms may have more than enough investment, but will need to navigate a range of regulations, unique from country-to-country, sometimes even from city-to-city.

The type of sharing also matters. It is less controversial to share your pet with someone who wants to take a dog for a walk than it will be to share a ride or a home with a stranger given that traditional industry already offers a similar, heavily regulated service. It is unlikely that blanket regulation will be possible for the sector given the differences between activities.

3. If the UK were to sustain large-scale platforms it would need to invest at scale rather than just at the start-up level. However, this would amount to investing in the establishment of UK-bred monopolies in the sharing economy.

As mentioned, these businesses benefit from ‘network effects’, which means that each new user of a platform increases the usefulness of the platform’s network for other users as well as its overall value. Coyle observed that there are global companies that are able to come into the market and run losses for years because they have investment at such a large scale. Venture capitalists are propping these platforms up while they are battered by regulators, supporting them to expand even as they haemorrhage money. For their troubles, investors are banking on ever lucrative returns as these platforms begin to show signs of growing monopoly power, or what the RSA refers to as ‘networked monopolies’.

It may be more challenging to deal with Silicon Valley’s tech behemoths in the UK (for example, there have been recent issues with how much tax Google is expected to pay here), but it would be unwise to invest in large scale financing of sharing platforms for the sake of growing our own giants. It is still very early days for the sector, and there is ongoing experimentation that could ‘disrupt’ these platforms just as they get comfortable.

4. Determining the rights of ‘gig workers’ is about to become the number one priority for on-demand platforms in the sharing economy.

‘Gig workers’ in the sharing economy take on a job at a time, similar to musicians playing gigs. Work is fragmented rather than continuous, which means that relying on gig work to sustain a livelihood can feel precarious.

The Committee were keen to hear our thoughts about whether gig workers (for example, drivers for Uber or cleaners for Hassle) in the sharing economy were being exploited or denied their rights. Gig workers are considered by on-demand platforms to be ‘self-employed’ or ‘independent contractors’ rather than employees, which means that in exchange for more freedom and flexibility they forgo other benefits and protections. However, not all gig workers have the same relationship with platforms; for some, picking up a job is seen as a casual opportunity for additional income, while for others these jobs have taken the place of full-time work.

For those that are gigging full-time, platforms may be seen as increasingly exercising control over terms and conditions, especially as a few become networked monopolies. Some certainly do, which is why GMB is currently supporting a number of Uber drivers to take their case against the platform to court (following the class action suit against the company in the US).

It may be that we need to explore a third classification of worker, or that platforms could improve their existing offer to gig workers without having to re-classify them as employees (which could potentially bankrupt their business). Juno, for instance, is a new platform launching in the US this spring that aims to put drivers before customers and will even give them the option of owning shares in the company. We need a better understanding of gig work, however, before we draw any firm conclusions about what is needed and whether the legal system should be overhauled.

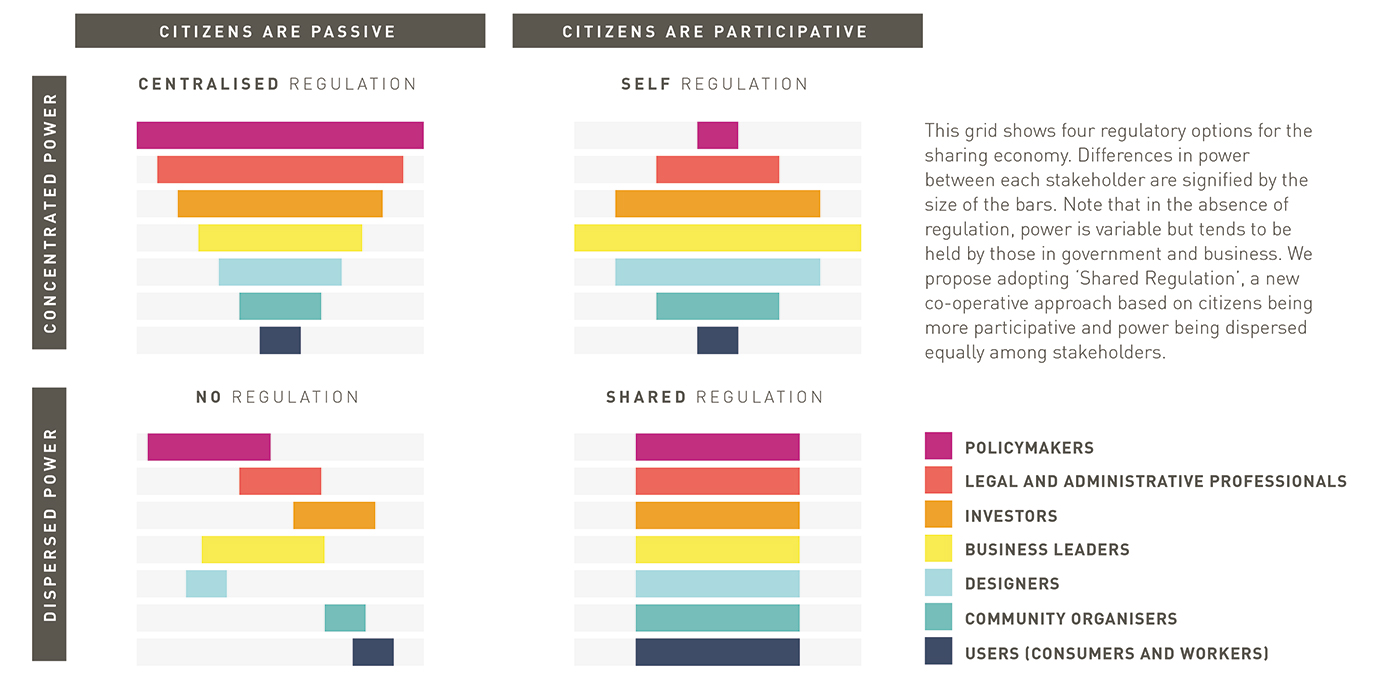

5. ‘Shared regulation’ must be further developed as the need for a new approach to governing the sharing economy becomes more urgent.

Businesses in the sharing economy are demonstrating that they are better able to master self-regulation when it comes to issues of safety and security than businesses in traditional industry have been. Through experimenting with technology (for example, two-way rating and review systems and instant background checking services) strangers are finding ways to trust each other and peer-to-peer services rather than just a few established companies.

However, self-regulation alone will not suffice because these businesses are having a wider impact on society. For example, traditional industry is currently lobbying the government to scrutinise the tax payments of Airbnb’s hosts. They envision a scenario where government can ask Airbnb to hand over their data on hosts’ incomes, but further into the future we may have a scenario where there is no intermediary platform owner that government can go to. Blockchain (the technology underpinning Bitcoin) is making it possible for genuinely peer-to-peer platforms to emerge, sans intermediaries.

Government must prepare for a scenario where they have little control or influence over platforms that are truly decentralised. Thus, working now with an array of stakeholders, such as designers and legal experts, but also – most crucially – users is critical. Users will have new responsibilities under the new economy, and government should start thinking through how users can play a role in ensuring that these platforms serve more than the interests of the network and benefit the common good.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Data is a the under-represented issue in this discussion.

The tendency has been to discuss the the sharing economy in terms of the things being shared (eg cars, accommodation) and not the data. The sharing economy has arisen primarily out of the ability to "datify" the products and services being shared, as well as the consumption of them. This has enabled businesses such as Uber and Airbnb to establish what are effectively closed marketplaces that match buyers and sellers. And in the case of Uber, set pricing.

Vendor and consumer data in these marketplaces are "owned" and controlled by the business. As such, the valuation of these enterprises are not primarily based on projected operational revenues, but the perceived value of the data in generating new revenue streams.

The impact of peer-to-peer technologies is a moot point insofar as it only address the transactional part of the "data marketplace" that underpins the associated sharing economy business model. Value creation occurs when data is shared.

Power in sharing economy models is intrinsically linked to control of data. (at topic for a wider discussion)

The notion of achieving "fairness" is very much linked to how data is governed in the interests of data contributors (business, citizens, public sector). To this end, governance models will be needed that reflect the nature of the underlying data marketplaces - encompassing the spectrum from "open" marketplaces, with shared commons, through to closed marketplaces.

Thus far citizens (on both supply and consumption sides) have been willing to accept a passive role in terms of their data by seceding control to the marketplace owner. However, as citizens become more self-aware and engaged in relation to their how they participate in sharing economy business models that utilise their data, the development of shared data platforms capable of providing them with control over how their data is shared may offer the possibility of a more dynamic sharing economy. This is one in which in which citizens have greater "data mobility", application providers have greater opportunities to participate on the basis of functional capability (and less in terms of data control), and where governance models might minimise regulatory complexity.