There is powerful evidence that points to old industrial towns and cities – those that arguably lost out most from sweeping economic change in the 70s and 80s – being one of the driving forces behind the UK’s decision to leave the European Union.

Brexit tends to be explained with reference to people (demographic) factors. In particular, a strong relationship is observed between age, skills levels, and voting patterns. The younger and more educated a place’s population is, the higher its Remain vote will be – and vice versa. Place itself does not matter much, but rather the sort of people that live in that place.

But focusing on individual characteristics in isolation (however statistically sound) obscures the geography and place-based dimensions of Brexit. Indeed, variations in ‘human capital’ are themselves given meaning by the uneven geography of growth in the UK. They are particularly important because they tell us something about who has been benefiting and who has been losing out from the modern economy.

But focusing on individual characteristics in isolation (however statistically sound) obscures the geography and place-based dimensions of Brexit. Indeed, variations in ‘human capital’ are themselves given meaning by the uneven geography of growth in the UK. They are particularly important because they tell us something about who has been benefiting and who has been losing out from the modern economy.

Rather dryly, analysts explain the gaping wedge between the economy’s winners and losers as a result of the “skills premium.” Our post-industrial, knowledge-based economy rewards high-skilled workers, leaving many of the least educated trapped in cycles of insecure and low paid work. The biggest driver of inequality in advanced economies is the unequal distribution of skills.

Importantly, the patterns of this inequality have a clear geographical expression. Some of the biggest losers of economic restructuring (or ‘modernisation’) have been Britain’s old industrial areas – those towns and cities that were historically reliant on traditional industries such as mining, steel and textiles. These industries (largely) collapsed under the weight of global competition, and were written off as ‘lame duck’ sectors by government.

Many of these places went from enjoying close to full employment in the 60s to being blighted by mass worklessness through the 80s and beyond. This was largely hidden from view by Margaret Thatcher’s decision to “park” hundreds of thousands of laid off workers onto incapacity benefits (the IB count went from less than 400,000 in 1963 to around 1.2 million by 1991, and close to 2 million by 1999 – and stands at around 2.5 million today). At precisely the time that these communities needed major human investment to support upskilling and labour market adjustment, their productive potential was sucked out of them by an indifferent government.

The consequences are clear to see: huge skills deficits, long term labour market neglect and multi-generational blight, resulting in a massive waste of human potential. It is the socio-psychological effects of decline that are perhaps the most scarring: once proud centres of economic power now experience the indignity of economic disconnection and labour market detachment. Some have come to be seen as failed towns, as places you do not want to work or invest in, or be proud to call home.

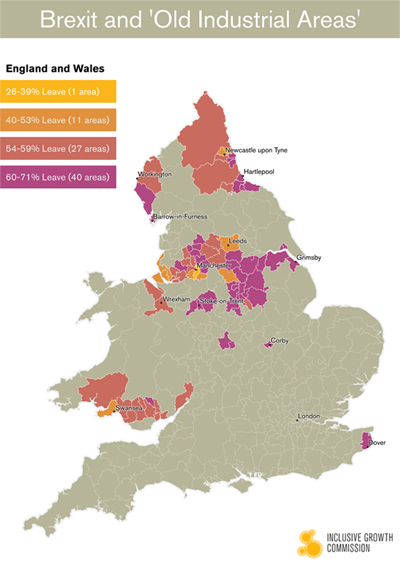

It is hard to argue that this detachment, decline and loss of pride helped propel the Brexit vote. We analysed the voting patterns of old industrial areas (OIA) for the Inclusive Growth Commission’s forthcoming interim report, using a classification of OIAs developed by the Industrial Communities Alliance. We found that the vast majority of OIAs in England and Wales voted to leave the EU at higher than the England and Wales average of 53%. Over half had Leave percentages of 60% and over, making up a significant chunk of the national cohort of High-Brexit areas (40 of the 102 areas that voted 60%+ for Leave were OIAs). Unlike England and Wales, OIAs in Scotland all backed Remain, which may well reflect an ‘SNP effect’ (it is worth noting that Scottish attitudes to the EU as an institution have not been substantially different to the rest of the UK).

The dynamics and variations within OIAs in England and Wales are striking. There is a clear ‘core city’ effect: the urban centres of city-regions make up the majority of OIAs where the Leave vote was below the England and Wales average. Newcastle, Sheffield, Leeds, Manchester and Liverpool had much lower Leave shares than their surrounding hinterlands.

This partly reflects their socio-demographic profile (i.e. urban populations that are younger, more ethnically diverse and higher skilled or with more university students). But it also highlights two very important changes in the relationship between larger cities and their hinterlands.

The first is that the big cities have been the focal point of public investment and successful regeneration over the last few decades. Leeds and Manchester in particular have been able to offset some of the damage of deindustrialisation by diversifying their economic base and adjusting their labour markets accordingly. This has been smoothed by government-supported efforts to reinvent the image of big Northern cities, helping to formulate public perceptions about their attractiveness as places to invest, study, work and live in. The focus on large cities has also grown as the theory of economic agglomeration has increasingly shaped the thinking and imagination of policymakers. By contrast, smaller towns and cities have suffered deep image problems. They have tended to be associated with urban ‘decay’ and intractable deprivation – fuelling low confidence, low aspiration and an inability to attract and retain talent.

The second observation is that the geography of growth and employment has changed dramatically since the 1980s. Not only are new jobs different, but they are also not in the same places as they used to be. Economic activity is increasingly centrally concentrated: within city centres, and within the centre of city regions. Many neighbourhoods in peripheral industrial areas are therefore fundamentally disconnected from the growth that is happening around them.

In short, larger OIA cities have come to be seen as economically dynamic and vibrant, as having a critical and meaningful place in the national economy. Meanwhile much of their hinterlands have had to contend with narratives of decline and dysfunction. Excluded from growth and perpetually written off by policymakers, it is no wonder their residents felt they had nothing to lose by voting against a powerful symbol of global capitalism.

Atif Shafique is Lead Researcher for the Inclusive Growth Commission

Related articles

-

Inclusive Growth and the Airblade Effect

David Boyle (blog)

How can our public services be at their most effective? Does the future entail wet or dry hands?

-

The avoidable costs of non-inclusive growth

David Boyle (blog)

Why does policy fail? David Boyle makes the case for the local integration of services

-

A country that works for everyone? Only with inclusive growth

Stephanie Flanders

Without inclusive growth the country will become more divided outside the EU than it ever was within it, argues Stephanie Flanders.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.