It may have been purely strategic brinkmanship, but it was concerning to hear Chancellor Philip Hammond threaten to turn the UK into a tax haven if it is shut out of the EU’s single market. Such a move would undermine the Government’s recent interest in inclusive growth – and push the economy ever more firmly into the hands of the super-rich. The Republic of Ireland should provide a cautionary tale.

Last July, the publication of Ireland’s annual economic growth figures sparked widespread bemusement. GDP had increased by a whopping 26 percent in 2015. EU and IMF officials urgently met with Ireland’s statistical authorities to verify the information; economist Paul Krugman called it “leprechaun economics.” The major reason for the unusually high increase: the relocation of a couple of very large international companies to Ireland, ostensibly to lower their tax burden. Under revised national accounting measures (developed by the UN and implemented by Eurostat), even though much of the economic output of these companies was generated outside of the country, the legal ownership of the output lies in Ireland. The rationale for the new accounting framework makes sense: it means global corporate tax-dodging becomes slightly more difficult. But it also exposes the fallacy of relying on GDP figures as the key measure of economic success (Ireland is now developing a new measure that excludes the effects of firms re-domiciling).

As the Inclusive Growth Commission argues, economic output measures do not tell us anything about the extent to which economic growth is being shared by different groups in society or between different parts of the country. The UK’s relatively impressive GDP and employment growth conceals the anaemic growth in household incomes (which is set to become much worse for the bottom half of households), the entrenched regional inequalities of economic performance, the persistence of low quality jobs and low productivity businesses, and the fact that many people, such as those with disabilities, are not really benefiting at all (the disability employment gap stands at 34 percentage points). This is why when Professor Anand Menon warned an audience in Newcastle that leaving the EU would hurt the UK’s GDP, the reply back was: “That’s your bloody GDP. Not ours.”

Dreams of high rates of GDP growth, multinational relocations, foreign direct investment and flattering positions in international economic rankings should not tempt us into a low-tax economy. Such a move would only entrench the problems with our current economic settlement, exacerbating inequalities and widening the chasm between GDP growth and improvements in living standards. The Prime Minister’s efforts to “make the economy work for all” would be completely undermined.

We know that the benefits of growth do not automatically trickle down. Simply lowering taxes and chasing foreign investment is no substitute for a balanced economic model that creates opportunities for all, drives higher productivity and incomes, and delivers more sustainable growth.

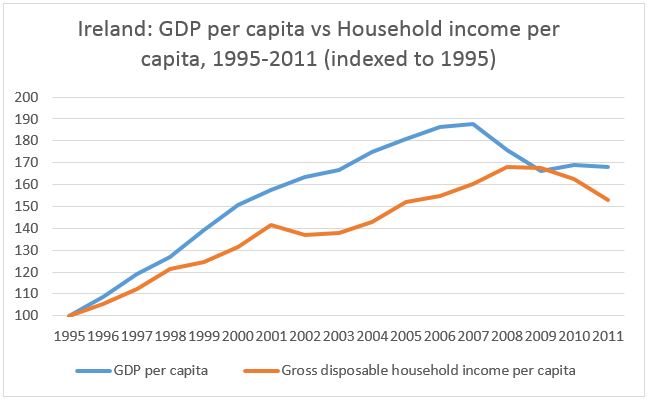

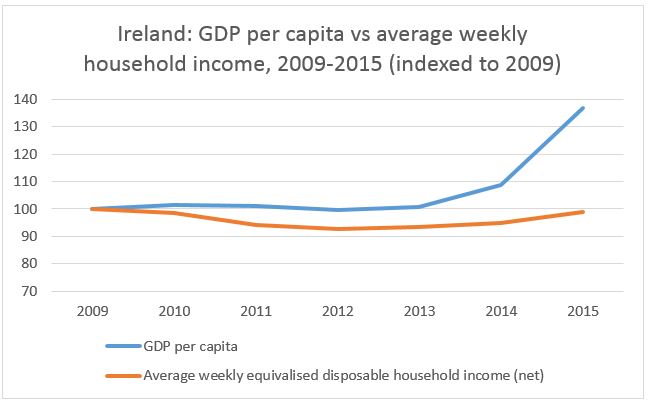

Ireland’s experience is illustrative here. It is one of Europe’s highest performing economies for GDP growth, but languishes below the EU average on household income measures. As the first graph below shows, since 1995 per capita GDP has risen much faster than disposable household income per person – in other words, the benefits of growth are not reaching people anywhere near as much as they should. The gap closed when GDP tanked following the global recession, but it has opened up again and threatens to become ever wider as household incomes stagnate or grow slowly while GDP growth bounces back. The second chart shows this is clearly happening (and would happen even under pre-2015 accounting measures).

Sources: Author’s analysis of data from OECD and Ireland’s Central Statistics Office. The figures used are inflation-adjusted and GDP is calculated using the expenditure approach. Note the first graph uses per capita GDHI while the second one uses average weekly equivalised disposable income.

If we are to truly create an inclusive economy, the UK must resist all temptations to pursue this sort of economic strategy. We already have some of the highest levels of income inequality and the widest regional economic disparities in the developed world. Our post-Brexit economy should be one that overcomes a narrow preoccupation with GDP growth. Instead, it must channel investment into helping more people and places participate in, and benefit from a new, inclusive kind of growth. To do this, we must ensure that the quality, and not the quantity of growth is our yardstick of success.

Atif Shafique is lead researcher for the Inclusive Growth Commission. You can find him on Twitter @Atif_Shafique.

Related articles

-

Exploring Inclusive Growth in Cornwall

Stephen Horscroft

Stephen Horscroft FRSA explores inclusive growth in Cornwall and the factors specific to the county.

-

Commanding a majority in the country, not just the Commons

Charlotte Alldritt

A new kind of coalition between Westminster and our major city leaders is needed to command a majority in the country – not just the Commons, argues Charlotte Alldritt.

-

Inclusive Growth and the Airblade Effect

David Boyle (blog)

How can our public services be at their most effective? Does the future entail wet or dry hands?

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.