There are now an estimated 1.1 million people in Britain’s gig economy, which is nearly as many workers as in the National Health Service (NHS) England. Over the last five years, the trend of using online platforms to source small, sometimes on-demand, jobs has accelerated, and shows little sign of slowing down.

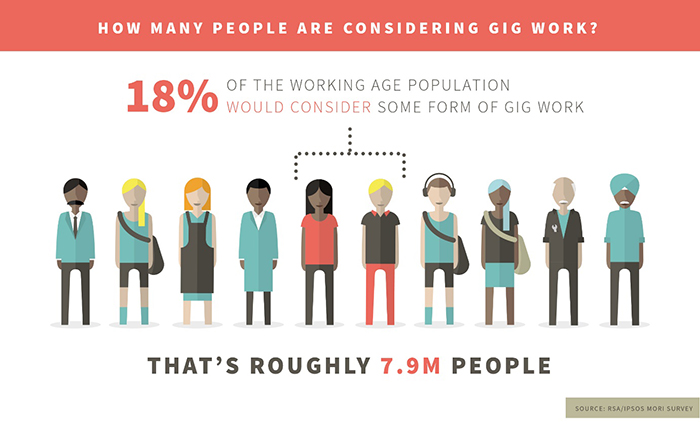

In the largest survey undertaken on Britain’s gig economy, the RSA found that nearly 8 million people in Britain would consider some form of gig work in future; young people (aged 16 – 30) are particularly attracted to the idea of gig work – one in four expressed interest in working in the gig economy. Given this enormous potential for growth of the gig economy, the RSA set out to envision how platforms can become a catalyst for fair, fulfilling work in the modern labour market.

How we as a society respond to the impact of gig work on the labour market is an early, and significant, test of how we will manage increasingly radical changes as a result of developments in technology, such as artificial intelligence and automation. The hope is that we can leverage technology for the benefit of workers.

- Read online: Good Gigs – A fairer future for the UK’s gig economy

- Download the report: Good Gigs (PDF, 2MB)

The uncertainty over how gig workers will fare over time, however, is making people feel uneasy about whether they will still have a decent standard of living in the wake of ‘disruption’. With this in mind, an incoming government needs to grapple with the reality of what changes in work will mean for society, recognising that the bedrock of security for most people – nine-to-five employment – is gradually disappearing. Not only does traditional employment guarantee rights and protections in the labour market, but it is also an important source of public revenue, accounting for a greater share of taxes per capita than self-employment.

For those increasingly concerned that platforms are threatening our social and economic security, the starting point has been to challenge whether gig workers should be considered genuinely self-employed. There is an urgent need for government to clarify the law and deter misclassification of workers. However, classifying workers appropriately under the law is also limited in its potential to transform workers’ experiences of the labour market. The law will not guarantee that work is fair in other ways that matter; for example, the law cannot guarantee gig workers more power over decisions that affect them or a larger share of the value that they’ve created.

Given that platforms operate in diverse ways and not all exercise the same levels of control, it is unlikely that all gig workers have been misclassified. Thus, only some workers will stand to benefit from the rights and protections conferred by a different employment status. Taking into account the wider trend towards self-employment (which was well underway before gig work became prevalent), it also needs to be considered that more people are valuing a higher degree of flexibility than most employees have. This leads us to believe that traditional employment cannot be the basis of a secure foundation, but rather this should be built on a broader conception of good work for all, irrespective of employment status.

The RSA’s view is that government needs to be clearer about how technological innovation – in this case, platforms in the gig economy – can raise the quality and security of work over the long-term. This means that government should continue to support platforms in the UK, but can no longer remain agnostic about the different business models used by platforms. Platforms do have the potential to empower workers through enabling peer-to-peer exchange, but they make different choices about how to operate, including how they treat workers. Through rethinking its approach to regulation, government can positively influence these choices.

At the RSA, we advocate for government to adopt an approach of ‘shared regulation’, which will require government to work in a more collaborative way and appeal to a range of stakeholders to help establish key tenets and principles of good work in the gig economy. Government may take the lead in distinguishing what good work looks like, but businesses and civil society are crucial in making good work a reality.

In truth, government needs platforms, civil society, investors, legislators, and workers themselves to ensure that gig work is actually aligned with its vision of good work. Ultimately, collaboration will enable government to shape the gig economy in a more strategic way than has been achieved so far by taking either a heavy-handed or light-touch approach to regulation.

In addition to revealing more about the nature of Britain’s gig economy, we make recommendations to shape the gig economy while it still nascent and malleable to change.

Our recommendations aim to:

- Account for the pressing questions about employment status and concerns that misclassification may be eroding public finances as well as workers’ protections.

- Begin building a new foundation of social and economic security that isn’t premised on traditional employment, but is based on good work for all.

- Address systemic issues in the labour market, such as a lack of support for atypical workers and promising new business models.

Ultimately, there is a larger question here about what kind of marketplace we want to enable in the UK, and our starting point needs to be the pursuit of good work.

Read the report online: Good Gigs – A fairer future for the UK’s gig economy

Download the report: Good Gigs (PDF, 2MB)

Listen to the RSA Radio podcast on the gig economy with Brhmie, Trebor Scholz (The New School, NY) and Olivia Sibony (Co-Founder, Grub Club):

Subscribe to the RSA Radio podcast: Soundcloud | iTunes | Pocket Casts

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.