The ‘gig economy’ is poorly understood, the term itself becoming a catch-all for anyone in atypical work. However, it’s important to clearly define the gig economy and distinguish its workers from self-employed freelancers or employees on zero-hour contracts, so that we can respond to emerging problems of protecting gig workers’ rights appropriately, while also balancing the interests of new businesses and the public.

The growth of Britain’s ‘gig economy’ has been profound. In a mere five years, companies like Uber and Deliveroo, which enable transportation and delivery at the tap of a button, seem to be fundamentally changing our ways of working.

It’s likely that some reading this will have recently taken an Uber to get around the city, or ordered a curry through Deliveroo on a night in. There may also be readers who are more familiar with being behind the wheel, or on a bike balancing a takeaway while skilfully manoeuvring through traffic.

These two companies in particular are in more than 75 towns and cities across the UK, while also expanding globally. Uber can be accessed in more than 500 cities around the world, while Deliveroo’s presence is strong across Europe. Both are acclaimed as ‘Unicorns’, which are start-ups valued at over a billion dollars; Uber’s worth has been pegged at as much as $70bn (£54bn).

When we refer to the ‘gig economy’, we are discussing the trend of using online platforms to find small jobs, sometimes completed immediately after request (essentially, on-demand).

Much like an actor or musician goes from ‘gig to gig’, workers in the gig economy are sourcing one job at a time, but by logging into an app or clicking through to a website. Each ride an Uber driver accepts is a ‘gig’ or a single job, as is each booking a Hassle cleaner makes to tidy a flat or every errand run through TaskRabbit.

In collaboration with Ipsos MORI, the RSA undertook the largest survey on the gig economy in Britain

RSA Survey on the British gig economy

We estimate that there are currently 1.1 million gig workers in Great Britain. Around 3 percent of adults aged 15+ have tried gig work of some form, which equates to as many as 1.6 million adults in Great Britain.

For some, this may be a smaller proportion of Britain’s workforce than imagined, especially given higher estimates that have encompassed the general trend of independent work or freelancing. That said, over a million workers in a relatively new market that is continuing to grow is significant. This amounts to almost as many workers as are in NHS England (1.2 million).

The gig economy has grown as an aspect of the ‘sharing economy’

While online platforms for sourcing gigs (in the form of ‘crowdwork’) have existed for more than a decade, the trend has accelerated in the UK since 2012 as an aspect of the ‘sharing economy’.

In the sharing economy, there are two kinds of platforms — asset-based platforms, and labour-based platforms.

- Asset-based platforms entail sharing an underused asset, such as a home, as hosts do on Airbnb.

- Labour-based platforms are premised on making the most of one’s skills or time, such as through driving for a few hours a week in addition to other commitments, such as another job, caring responsibilities, or creative pursuits. These are the platforms in the gig economy.

What services are being provided in the gig economy?

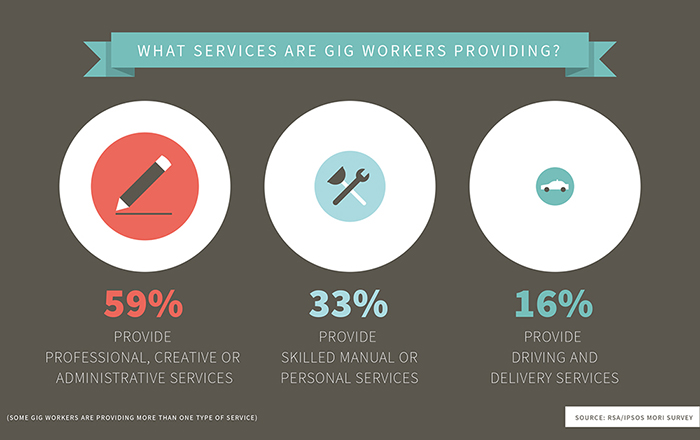

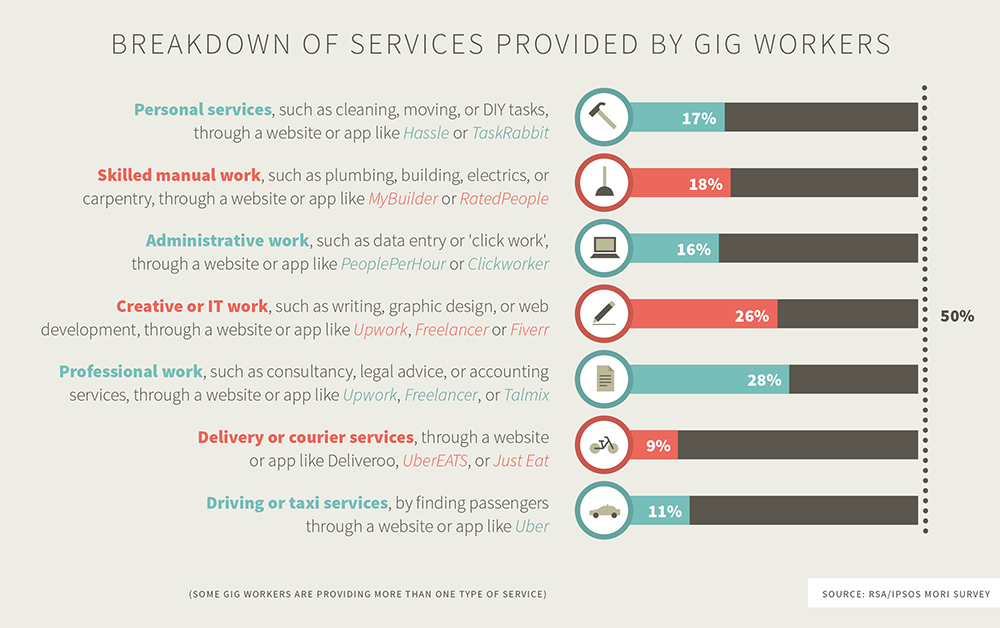

In a recent RSA report evaluating the UK gig economy, we found it useful to group gig work into three main categories:

- Professional, creative or administrative services

- Skilled manual or personal services

- Driving and delivery services

Well over half (59 percent) of gig workers are found in professional, creative, or administrative services. This was to be expected given that before the rise of the ‘sharing economy’, platforms had been established mainly for freelancers, such as copy editors or graphic designers, interested in finding consultancy opportunities.

A significant number of gig workers provide skilled manual services, such as plumbing, electrical maintenance, or carpentry. Workers in the skilled trades who are self-employed have long been sourcing jobs online through platforms such as MyBuilder and Rated People, both of which were founded circa 2005.

It may surprise some that gig workers providing driving and delivery services were found to be in the minority. This may be because of the high visibility of these workers on our roads in contrast with freelancers working from home, or for example, plumbers or electricians disappearing into other people’s homes to carry out their tasks.

However, given that driving and delivery platforms were the most recent to be established in the UK, this too should tally with our expectations. This is still a substantial share of gig work given these platforms only emerged within the last five years.

Note: some gig workers are providing more than one type of service

Are gig workers employees or self-employed?

The online platforms hosting or offering the gigs tend to consider gig workers as self-employed, or ‘independent contractors’, citing the flexibility they have over choosing their own hours. The gig economy is thus sometimes conflated with the general trend towards self-employment or ‘independent work’.

Some argue that platforms are misclassifying workers as self-employed, depriving them of rights and protections while still exercising control akin to employers. There are also concerns about how this affects public finances because the self-employed and the companies that contract them pay a lower rate of tax than employees and the businesses they work for.

Both the RSA’s report on the gig economy and the Taylor Review on Modern Employment Practices reached the conclusion that how a worker is classified should be decided on a case by case basis rather than assuming that all workers in the gig economy fall under a particular category. However, the Taylor Review sought to clarify the ‘worker’ category – a third category that sits between employee and self-employed – renaming it ‘dependent contractor’ and specifying the rights and entitlements to be provided. It is likely that many gig workers will be reclassified as ‘workers’/dependent contractors, especially given that a tribunal recently found two Uber drivers to be ‘workers’ rather than self-employed as claimed by Uber.

The Taylor Review was a much anticipated milestone in progressing the debate on employment rights of gig workers. Our next blog will delve into the detail of this debate and its implications for workers, businesses and consumers.

- Further reading: Taylor review - pragmatism must prevail

- Download our report ‘Good gigs: a fairer future for the UK’s gig economy’

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.