As we sit on the cusp of a fourth industrial revolution, the potential of any Industrial Strategy should be transformative, but it won’t be without a fundamentally new approach to innovation.

Automation, robotics, machine learning and biotechnology provide unprecedented possibilities for tackling our most pressing social challenges, from climate change to an ageing population to intergenerational cycles of poverty. Yet for the fourth industrial revolution to be “empowering and human-centred, rather than divisive and dehumanizing” as Klaus Schwab hopes, we must think deeply about these social challenges, while innovating fast and busting out of old models of change.

When it comes to public procurement, capitalising on the promise of the fourth industrial revolution will require ripping up the book and starting again. Government needs to ‘think like a system, and act like an entrepreneur’.

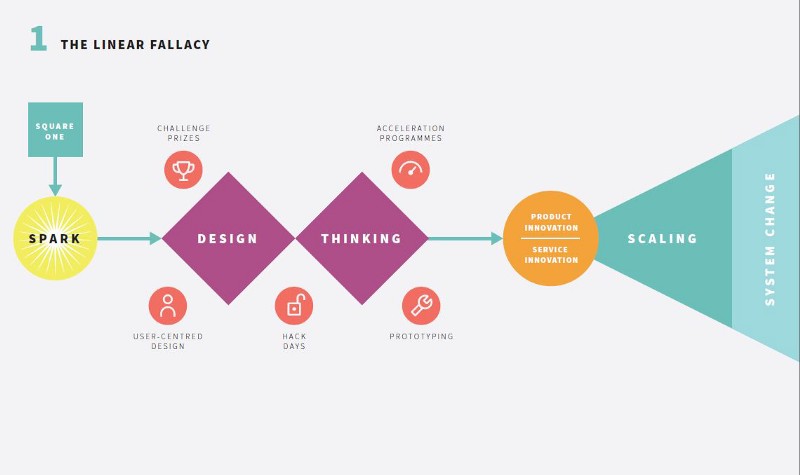

Why the need for such drastic change? While businesses and social entrepreneurs are deploying design thinking methodologies to generate fresh products and services, the problem is channelling these innovations to scale – entering the system to generate impact.

It may be that our understanding of how innovations diffuse is out of date – we still lean on the innovation adoption curve developed by E.M. Rogers back in 1962 that shows the pathway of an idea or product as it diffuses through a social system. It has become so ingrained in our understanding of innovation adoption that when we talk about scaling or diffusion it is implicitly this path that we depend on.

This model of diffusion is predicated on belief in a step-by-step innovation process; sadly, this constitutes a linear myth:

The reality is that the diffusion of innovations — particularly emerging technologies and or those addressing complex social challenges — are far from predictable and markets aren’t as clearly defined as they once were. As the Gartner Hype cycle shows, the pattern of diffusion is ever more complex and impossible to predict.

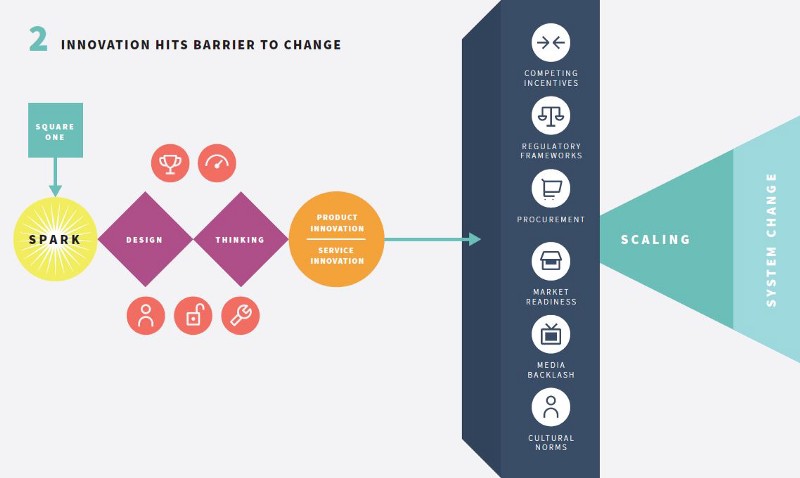

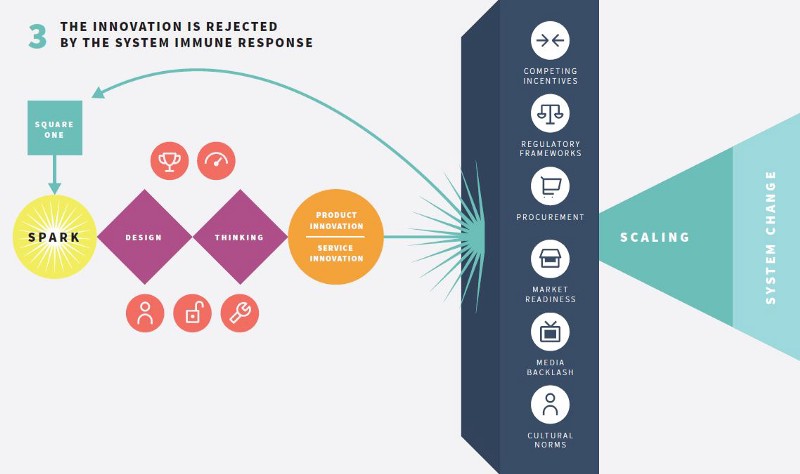

In 2009, Harvard professors Robert Kegan and Lisa Laskow Lahey developed the concept of Immunity to Change. When individuals try to make a change — perhaps weight loss or a career change — they are inevitably confronted by a range of powerful forces that combine to reject the change. We see parallels with this immune response in the diffusion of innovations into institutions and markets. This institutional “immunity to change” arises when market or institutional norms form a barrier to entry or scaling. Rather than an easy and linear route to diffusion, innovations become bogged down in ‘reasons why not’.

These barriers to change will of course vary wildly depending on what the innovation is that is trying to scale. Complex systemic barriers can be hard to map: they range from the hard reasons why not — the regulatory frameworks that don’t exist yet to permit a new innovation or the procurement binds that prevent access to markets — to the soft and messy business of human behaviour and power dynamics. The result is often the failure of the innovation to gain traction in the market: the system immune response.

Rather than hoping that the dividends of the fourth industrial revolution will simply find their way to addressing pressing social challenges, we need a new approach that acknowledges and confronts the complexity outlined above. Here we offer ‘think like a system, act like an entrepreneur’.

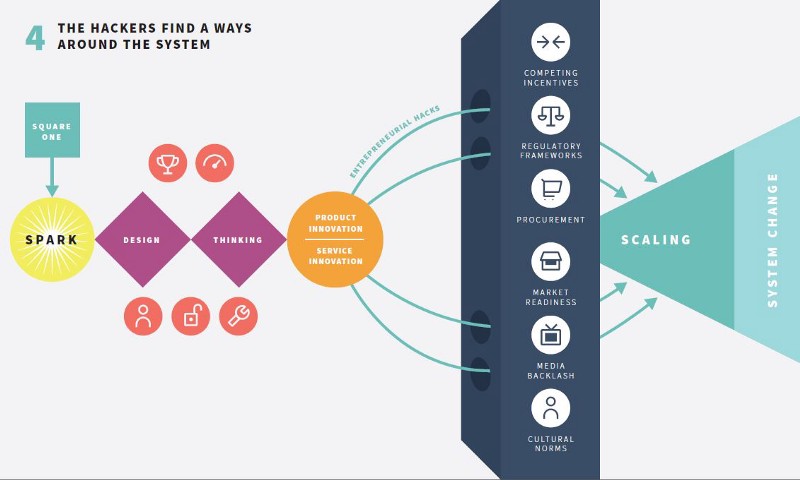

The next blog in this series will unpack ‘think like a system, act like an entrepreneur’ in more detail, but its basic premise is that actors should comprehensively map the system into which they hope to innovate – its power dynamics, key actors, enablers and disablers – in order to identify the most promising opportunities for change. Innovations can then be tailored to capitalise on these openings in the vein of entrepreneurs.

A new playbook

Entrepreneurialism is an attitude – it’s about being nimble in order to spot the hacks that will permit an innovation to permeate the hard barriers to change. The workarounds, the methods that defy regulatory boundaries, the cultural shifts — these are the hacks that provide routes to scale. And as Matthew Taylor recently wrote, it is the entrepreneurial confidence we need to seize to try these hacks out: “the stretch target for policy is innovation; creating the confidence to try things out and the culture and systems which mean failure can be tolerated and learnt from quickly.”

To optimise the promised bounty of the fourth industrial revolution for social good, understanding and taking action on the real barriers that block change is what might just lead to breakthroughs in adoption and scale of innovation. At the RSA, we seek to avoid the narrowness and path dependency of so many unsuccessful models of change. Understanding the dynamics of the system and then seeking opportunities to act entrepreneurially should help would-be innovators avoid the dreaded institutional immunity to change.

We must not be paralysed by the fear of the wildly varying predictions about our future. As Anne-Marie Slaughter, President of New America, points out: “we need to stop waiting and start addressing changes that we can already see happening around us.” To act swiftly and with competence in rapidly changing times is the modern challenge for government, business and society. In the next blog we will talk about applying new ways of thinking about public procurement and acting effectively as our world is disrupted.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Rory Sutherland always has thought-provoking things to say on choice, influence and the role of marketing in changing individual and organisational human behaviour - a

Rowan,

Thanks for this. Very enjoyable. You might enjoy Michael Grubb's notion that there are three co-evolving pairings which are crucial in innovation:

- technology and organisation

- market (clients and suppliers) and financing

- regulations and infrastructure

He argues the maturing of a technology needs an organisational 'host' which is similarly mature, the pairing of which needs markets and financing of similar maturity, which in turn needs regulations and infrastructure which can cope. See Planetary Economics.

David

This is a huge challenge, one that has concerned me for some time and a worthy focus for the RSA. I suspect that the first part of 'think like a system, act like an entrepreneur’ is the easier part of the challenge aided by digital technologies and the system transparency and insights they can provide. Acting like an entrepreneur without being an entrepreneur is a tough ask (and one I feel doomed to failure) but I think the intent is right and worth exploring. I look forward to contributing where I can.