It’s been two months since we ended the RSA Citizens’ Economic Council deliberations, and after a pause it seems like a good time to reflect on what we learned.

The key lesson is that these participatory processes have a profound impact on those involved. Not only have they an intrinsic value in themselves, but they could have instrumental value in helping policymakers earn legitimacy and create robust policy.

We should also start thinking of participation as two sides of a coin: with citizen engagement on one side and institutional responsiveness on the other – helping those who actually commit to participation meaningfully, build their trustworthiness.

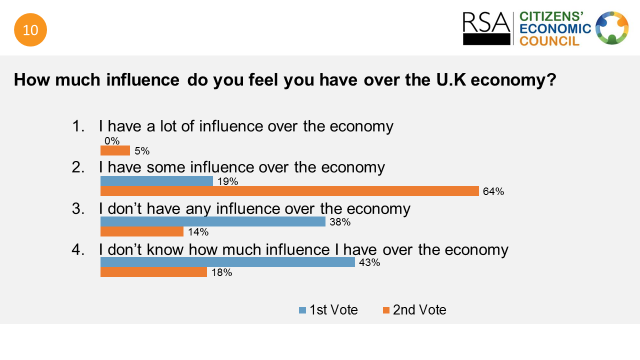

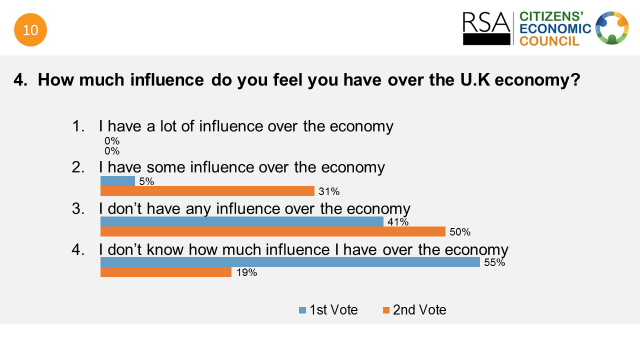

Changing perceptions of influence over the economy

Below are two bar charts showing responses from some e-voting the two groups involved in the Citizens’ Economic Council did on the same question, asked on Day 1 and Day 4 of the deliberative process. Both show that the percentage of people who didn’t know how much influence they had over the economy decreased by more than half.

London

Manchester

[Disclaimer - these figures must be taken with a slight pinch of salt as we did not have exactly the same participants voting on both days, but there are useful for identifying a general trend across the two groups.]

In their yearly Audit of Political Engagement, the Hansard Society measure levels of public knowledge, interest and perceived sense of influence over decision-making as a way to gauge how likely the public are to get involved in decision-making. The idea being that people with higher levels of these factors are more likely to participate.

If this holds true - and as suggested by the feedback and e-voting data we collected during the council, the process improved our citizens’ sense of confidence to talk about economic issues and sense of influence over the economy - these types of deliberative processes can play a key role in strengthening the health of our democracy.

Intrinsic value for the citizens

I do not have my head buried anymore, I am ready to ask questions and challenge

There was also value to being involved in the process on an individual level. Many participants told us that they may have initially signed up for the incentive payments we were making for their time, but that they kept coming along because they were interested in being involved in the council itself.

Several citizens have gone on to play a more active civic role after the council deliberation days, which again contributes to building our democracy, if you believe that democracy is more than just a vote once every time the ruling party says so.

Four of our citizens visited the RSA House in July to meet with our Chief Executive Matthew Taylor and discuss the importance of good work in our economy. Others are considering becoming councillors in their local neighbourhoods, and one of our council members has single-handedly convinced her team at work to increase their pension contributions after an ‘expert’ we invited to one of our council days spoke about the role of the state and individual contributions in saving for future life.

Trustworthiness and legitimacy

Scrutinise how I vote based on government party policies

As a collective our citizens were more confident at the end of the deliberation days, but also more aware of what they didn’t know, and more critical of political and economic leaders and institutions. Some of our citizens told us that they felt they were right to be sceptical, and hold a certain level of mistrust in political actors in order to hold them to account. This fed into our own thinking on the difference between trust and trustworthiness, where trust is something earned by being trustworthy.

The stated purpose of our public leaders and institutions is to serve the people, and when they fail to do so we should not blindly follow rather challenge them to improve. A couple of our citizens argued that this is also true of private institutions, as it is from our society that they run their businesses with (most often) publicly educated staff, publicly funded infrastructure and consumers to buy their products.

..policy making is much harder than one might think, you struggle to think of all the consequences of any one measure proposed

From the feedback we collected, it was clear that the interaction with ‘experts’ was one element of the whole process that the citizens enjoyed the most. They were interested to learn about the structures and agendas within institutions such as the NHS, the Bank of England, pension funds and local authorities.

After sessions interrogating these ‘experts’ and trying to create policy themselves, our citizens reported that they had greater levels of sympathy and understanding in how difficult it is to create policy in such a complex interdependent socio-economic system.

If this process helped our citizens understand the economic system and sympathise with those making the big decisions on how to run it, could deliberation be used more widely as a way for economic institutions to build their trustworthiness and thus legitimacy in the eyes of the public? We think this is a question worth exploring, and it raises other important points such as: What does legitimacy look like? How do we ensure economic institutions conduct these processes in a meaningful way? Can we rely on these processes to create socially beneficial outcomes for both the citizens involved and those who aren’t?

As a start to thinking about some of these questions… Citizens told us:

They want greater transparency

Transparency is not just about providing information but doing so in a way that is accessible – it is about using inclusive language so that you don’t need an economics degree to know what is being said in the news.

The Bank of England may publish its minutes for the quarterly meetings when the Monetary Policy Committee set interest rates, but our citizens said that it was such a boring way to present information that it may as well not exist. Instead, they said that if politicians and economic institutions wanted to become more transparent, they would need to think of new ways to present information so that it is more engaging. This could include working with media sources and celebrities to make information more accessible to younger generations; one suggestion was inviting George Clooney to present the Bank of England’s minutes via YouTube video!

They want engagement at different levels

Many factors influence whether and how much someone wants to participate in making decisions on the economy. Our citizens wanted barriers to be removed so that anyone could be involved as much as they wish to be. They thought it was unreasonable that it was always the people with higher levels of education, who had more time or could afford childcare, who got involved in local politics or community organising and were able shape decisions most actively.

In addition to this, they expressed the sense that some people may not want to get involved and make decisions themselves; but that people always want their views to be listened to and represented faithfully so that the final decision considered their interests.

One innovative example that tries to address this and create different avenues for involvement is the initiative run by a local authority, Kirklees, through their Democracy Commission. The Commission has held local democracy roadshows, public inquires, group discussions and deliberations to pull together recommendations for how to strengthen democracy in Kirklees. The commission recently came up with 48 recommendations including ideas such as: a young councillors’ apprenticeship scheme, a democratic digital literacy pilot, and the creation of video narratives in advance of a significant issue being discussed by the council.

Diversity brings legitimacy and effectiveness of policy making

Participants told us that it’s not that the public (and the youth in particular) are apathetic or don’t care about politics. It’s that they don’t see anyone in politics who represents them, so why would they want to engage?

This is the most diverse parliament we have had in history and yet it remains hugely unrepresentative of wider society; with high numbers of privately educated politicians, and still too few female and BAME MPs. On reflection, it makes sense that our citizens were so sceptical. They said that the lack of diversity of representation in politics also meant that the decisions made consistently benefitted the same groups of people and solutions offered were very narrow.

Policy made by considering many different perspectives would benefit from a wider array of solutions, and better understanding of how different groups (including economically excluded groups) within the system would be affected. Thus, they argued that policy which considered diverse perspectives would be more effective, or at the very least more legitimate as it would be considered more representative of the general public.

Whether that is something to be achieved through a truly representative parliament, or through experimenting with democratic innovations such as the Citizens’ Economic Council, is yet to be seen – but why not aim for both?

Related articles

-

Why Theresa May should reach for her inner Pankhurst: time for a National Citizens’ Jury on Brexit

Ed Cox

Ed Cox argues why we need a National Citizen's Jury on Brexit.

-

Two countries - polarised until we fix our democracy

Anthony Painter

Anthony Painter explores what the local elections say about the state of British politics and what that means for our ability to confront common challenges.

-

Democratic deliberation should be an integral part of policy making

Matthew Taylor

Matthew Taylor discusses why democratic deliberation is his chosen topic for his annual lecture.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.