Today, MPs from two select committees (Work and Pensions and Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy) presented draft legislation intended to ‘close loopholes that enable dubious business practices’. On the whole, it’s a welcome intervention that will hopefully nudge the government to act on key recommendations made by the Taylor Review.

However, we now urgently need to focus on how we tax companies for the use of self-employed labour and ‘workers’, which would mean closing the biggest loophole of all. By introducing the equivalent of Employer NICs for platforms or other companies contracting the self-employed or ‘workers’, the Chancellor could resolve the growing hole in public finances caused by the rise in atypical work.

Today’s draft bill reiterates the need for greater clarity on definitions of employment status. It echoes the Taylor Review’s recommendation that the legislation should emphasise the importance of control and supervision of workers by a company, rather than a narrow focus on substitution, in distinguishing between workers and the genuine self-employed. In other words, the courts should make a call on whether someone is a ‘worker’ based on how controlling the business is being (by, for example, requiring the wearing of uniforms or intervening in how tasks are performed) rather than on whether a worker can find a friend to cover his or her gigs. If this were to be introduced, we might see Deliveroo riders also win the right to minimum wage and holiday alongside Uber drivers after recently losing their claim on the basis that they have the ability to substitute their labour.

There is also a questionable proposal in the bill to implement a ‘worker by default’ model, which would apply to companies with a self-employed workforce above a certain size (to be defined in secondary legislation). We have made this point many times, but considering that not all gig economy companies operate in the same way and some impose more control than others, it is problematic to assume that all platforms are misclassifying their workers. Grub Club, for example, connects skilled and amateur chefs with customers who are up for sharing dinner with strangers; although the platform charges commission, it allows chefs to host at their convenience and set their own prices. It is entirely plausible for platforms to devise business models premised on using self-employed labour, a point also made by the judges of the employment tribunal case against Uber.

It is easy to imagine the ‘worker by default’ proposal backfiring when it comes to crowdworking platforms in the gig economy, such as Fiverr and People Per Hour, which have tens of thousands of workers picking up tasks that can be done remotely, such as graphic design or proofreading. Nevertheless, it is clear that through legislative changes there will be scope for more gig workers to be reclassified as ‘workers’ in future.

It’s now necessary to bear in mind that the employment status of gig workers has wider implications for tax collection. Even if more platforms class users as ‘workers’, this will not make much of a difference to the Treasury since ‘workers’ are considered self-employed for tax purposes.

In addition to protecting gig workers, changes must be advocated for to protect our tax base from being eroded by the gig economy.

Protecting public interest as well as workers

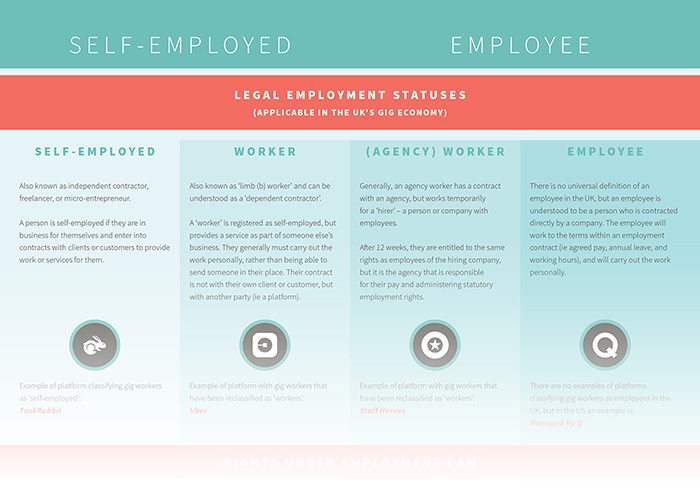

We made a chart to help make sense of different employment statuses applicable in the gig economy.

As you’ll see from the chart, ‘workers’ in the UK can essentially be understood as self-employed, but are extended some protections afforded to employees in recognition that they are not in business for themselves. They are sometimes known as ‘limb (b) workers’ (a reference to the legislation) or ‘workers in the extended sense’.

In a leading case before the Supreme Court in 2014, the judge, Lady Hale, clarified the meaning of a ‘worker’:

“…Our law draws a clear distinction between [employees]… and those who are self-employed… within the latter class, the law now draws a distinction between different kinds of self-employed people. One kind are people who carry on a profession or business undertaking on their own account and enter into contracts with clients or customers to provide work or services for them… the other kind are self-employed people who provide their services as part of a profession or business undertaking carried on by someone else.”

The precedent set by this case means that gig workers who are reclassified as ‘workers’ will continue to be considered self-employed, although given they are not in business for themselves they will be extended some key protections; for example, they are covered by minimum wage legislation and working-time regulation. This may resolve issues of workers’ rights in the gig economy to some extent, but it does not address the growing deficit in public finances as more people move from employment to forms of self-employment, sparing platforms like Uber from paying Employer NICs.

According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), NICs were forecast to raise £126.5bn in 2016/17, the vast majority of which will be Class 1 contributions, paid by both employees and employers. NICs are the second largest source of revenue for the government, behind income tax and ahead of VAT.

While it would be political suicide to make another attempt to equalise the rate of personal NICs paid by employees and the self-employed after last year’s U-turn, the Chancellor could have more traction for reform by addressing the matter of appropriately taxing those who use self-employed labour (and ‘workers’ by extension) instead of targeting the self-employed themselves.

If Uber, for example, had to pay Employer NICs, tax lawyer Jolyon Maugham reckons that the platform alone would accrue costs of around £13m per month (or roughly £156m annually).

Given the number of platforms in the gig economy and, more generally, the increased reliance on self-employed labour, it would be a missed opportunity if the Chancellor didn’t try to address this discrepancy in this week’s Budget.

The RSA has previously suggested different options for introducing such a tax including:

Payroll tax plus – Employer NICs are reconstructed as a ‘payroll tax plus’, with companies paying a levy for all workers they employ or contract, including the self-employed, whether independent contractors or ‘workers’.

Transaction tax – Employer NICs is converted into a ‘transaction tax’ to be paid by the consumer

It’s likely to address the tax problem in the gig economy, a combination of options is needed. It might also be simplest to only tax intermediaries who use ‘workers’ at this stage, but government should ultimately indicate the best way forward and take action to protect the public purse.

Read our report on the gig economy online: Good Gigs – A fairer future for the UK’s gig economy

Download the report: Good Gigs (PDF, 2MB)

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.