We passed a long line of brightly painted trucks that stretched as far as the eye can see. They were queueing to load up with grain to distribute across Somaliland and Ethiopia.

In an operation of byzantine complexity, a ship had just docked in Berbera port, laden with 47,000 tonnes of grain from Eastern Europe. It was paid for by the World Food Program (WFP) and distributed by a Canadian company, using conveyors and bagging equipment made in the UK and operated by a team of Pakistani engineers. ‘We really love working here’ they told us, ‘this is where the real money is’.

To be sure, the aid industry is immensely profitable for the few who manage it, and this particular team made a profit of US$300,000 in 5 days. The intended beneficiaries are harder to identify. ‘Why do they always send aid at harvest time?’ A local woman asks suspiciously. Farmers can’t compete with free food, so what’s the point of farming?

We were on our way to a patch of land, some 15km outside Berbera, that the Somaliland Government had lent us to build a pilot Seawater Greenhouse. Construction was nearing completion. Its purpose is to grow food, using fresh water made from the seawater, which also cools and humidifies the growing environment. The ever more concentrated brine eventually crystalises as marketable sea salt, another by-product of the process. The system is self-sufficient, produces its own water and energy from seawater and sunlight, respectively, and is drought proof.

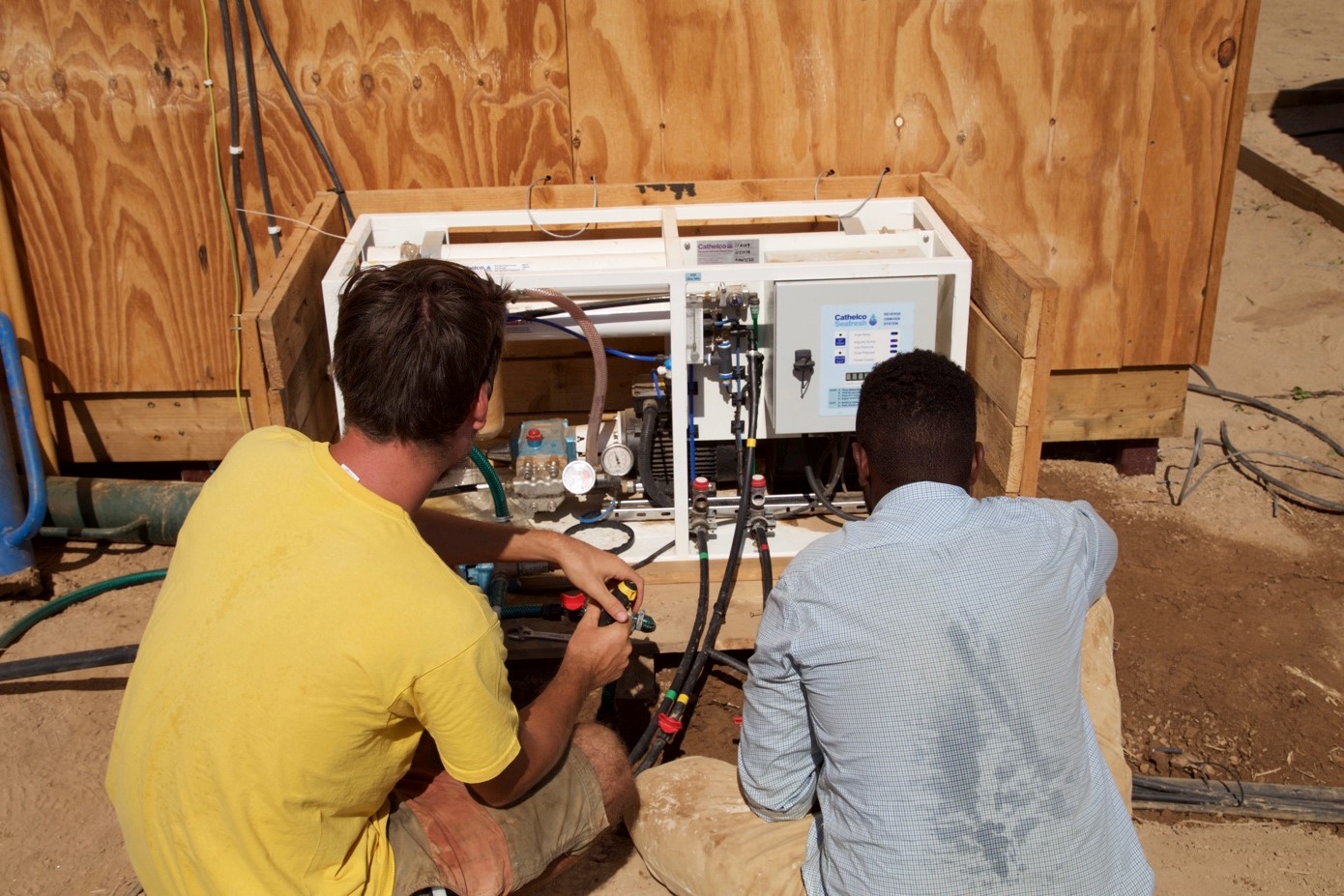

That week we had just fired up our seawater desalination system, powered by sunlight. The first in the entire Horn of Africa, we were shocked to find. How can it be that in a region that is continually racked by drought, no one has yet to install a desalination system? Could it be that the ‘famine-follows-drought’ mantra is the primary driver and fundraiser for the aid industry, and breaking that link threatens the very existence of the industry itself?

Yes, it may be a bit more complex, but Bob Marley hits the spot with ‘Them Belly Full (But We Hungry)’ - “a hungry man is an angry man, a hungry mob is an angry mob.” Conflict and famine are never far apart in the Horn of Africa, but we don’t see ‘famine-follows-drought’ in Australia or California, where similar water shortages exist. There are many social, economic, and environmental reasons the two appear to be inextricably linked, but the one that does not seem to get talked about is that there are enough people who make a handsome profit from it.

Will the first, self-sufficient Seawater Greenhouse in the Horn of Africa break that link and be the first of many? It is too early to tell. Certainly, that is our intention and there is no technical, practical, or commercial reason why it should not. There are however, many powerful players in the food aid distribution business and much money is made maintaining the status quo across the entire supply chain.

What makes it worse is that the aid industry has created a handout culture, such that everyone knows they will get by, just about, so long as they play the game. No one likes this degrading state of affairs as it undermines effort and ambition to collaborate, while promoting ambitions grab a larger portion of the pie. Local efforts to innovate and work collaboratively to create a larger pie for everyone are therefore stymied.

We certainly do not have all the answers to these complex problems, but are nonetheless trying to do our part by introducing sustainable and drought-proof agricultural technology to the region. The Seawater Greenhouse team have spent years working with Academic and NGO partners to custom-design the system for the harsh conditions in the Horn. Now it is built. It was developed specifically for smallholder family farming units as this will enable women to contribute, who we know will be key to the solution that brings the region forward.

Today we have a modest one hectare pilot. It is producing tomatoes, cucumbers, and freshwater for plant and human alike. But importantly we have shown that by pooling the knowledge and efforts of a dedicated UK – Somaliland team, and adding a bit of sunlight and seawater, there are alternatives to the current status quo. And as the pilot expands we hope this will lead to a brighter (not to mention greener) future in the region.

Charlie Paton is a product developer, maker and designer and is a Royal Designer for Industry. His early success was the invention and development of motorised lighting for theatre, TV and concerts. For the past 20 years he has been developing his Seawater Greenhouse concept. The design has received many awards; most recently the Climate Change Product of the Year and it has attracted attention from all over the world, including from the National Geographic and New Scientist.

Chris joined the team at Seawater Greenhouse Ltd. after winning an RSA Student Design Award in 2015 for his design of a water filtration kit for women in third world countries. Charlie was one of the judges of the competition and introduced Chris to Seawater Greenhouse after his success. Using the skills he learned from his Master’s in Engineering in Product Design and Manufacturing Engineering from the University of Nottingham, Chris is designing and developing the next generation of Seawater Greenhouse solutions’.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.