Everyone has an interest in the success of the economy. But it’s not always easy for the public’s voice to be heard in the rough and tumble of economic debate. The question is why?

Indeed, this is part of the reason I was so keen to answer the call to become a member of the Independent Advisory Group to the RSA’s Citizens’ Economic Council. How can you get members of the public engaged and involved in economic decision-making?

As Reema Patel argues in her article 'Economics anyone?’ there is a real need given a lack of transparency, legitimacy and accountability in aspects of current economic practice.

There is a language issue here. Economics, like many disciplines, has its own lexicon – who really understands what much used terms like ‘GDP’ and ‘GVA’ mean? Indeed, as Bobby Kennedy once famously remarked, GDP “measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.”And yet, when you unpack the economist’s toolkit, as the Citizens’ Economic Council has done, it’s clear that most people have a very good understanding of many of the aspects of how the economy works (or doesn’t) for them.

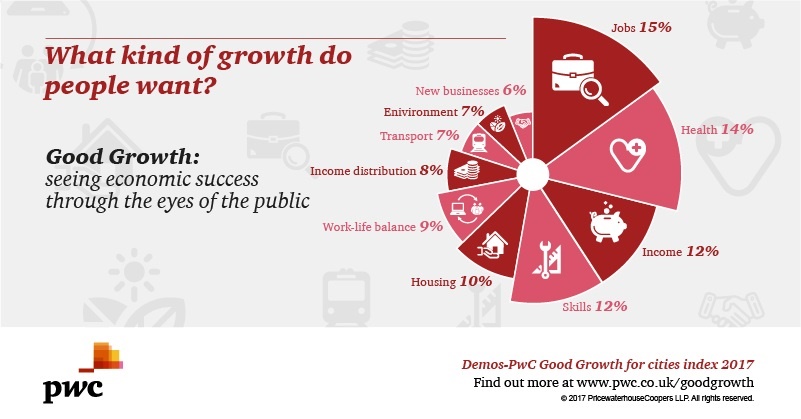

This was brought home to me by the research PwC has done with Demos, where we’ve had our own experience of how deliberation with the public can really excite and enrich the conversation on the economy. Indeed, a citizen’s jury event set us on the road to defining what has become the annual Demos-PwC Good Growth for Cities Index, based on views from the public on what economic success means to them. Within the index, good growth encompasses broader measures of economic well-being including jobs, income, health, skills, work-life balance, housing, transport infrastructure and the environment – the factors that the public have told us are most important to the work and money side of their lives.

Economic policy is often ultimately about choices and priorities – where to take action and invest scarce resources to promote growth and/or improve the distribution of its proceeds. This sort of index provides a framework for allocating resources and investment, driving decisions based on what people want. This is also a way to move beyond the narrow confines of GVA and, in this case, for city leadership to start with the outcomes that people – the voters – value, and so provide a more democratic dimension to the decisions made.

Our experience of such deliberative methods goes back further, starting with our response to the consultation on the 2010 Spending Review when it was clear that it had some pretty tough decisions to make about where and how to make the spending cuts. We felt the public really needed to be heard in this process, particularly in terms of what criteria government should be using when making its choices, so we collaborated with Britain Thinks to develop a citizens’ jury where people were provided with the space, time and information to really explore the issues and respond meaningfully.

So what’s the benefit of this sort of engagement?

Three things come to mind. Firstly, it offers the chance for informed deliberation. Although economic issues are in the news all the time, the information isn’t always presented in a way that makes it easy for the public to grasp. It’s therefore important to spend time helping people to understand the nature and complexity of an issue, whether it’s about intergenerational fairness or dealing with the fiscal deficit. Bringing in experts who present issues from different points of view is an important part of the process. Just like in a court of law, jurors can weigh up the evidence and come to their own informed view.

Secondly, a citizens’ jury offers a chance to explore trade-offs. For instance, you can’t ask the public questions about the impact of spending cuts or tax changes on the economy and expect to get simple ‘yes, no’ answers. These are complex issues, which need careful consideration and judgement.

Thirdly, deliberative approaches are more inclusive – you’re involving the public in discussion, understanding what they see as important and seeing things from their point of view. This adds legitimacy and transparency to the process. People also need to know that their views are important if they’re going to stay involved. We can see in other countries how powerful such groups can become if they become trusted to represent the public’s voice in the heart of the decision-making process, such as the Alders’ Table, founded to steward the future of the Netherlands’ Schiphol airport.

The acid test though is the extent to which government embraces these principles and sees this work as an integral part of testing, designing and implementing economic policy. That’s why ideas proposed by the work with the CEC such as piloting this type of approach with institutions involved in economic policy making hold such promise as a legitimate, transparent mechanism. If institutionalised within the economic decision-making process, they could also add real accountability.

Involving the public really is the best way to add meaning and legitimacy to economic policy-making. In doing so, we could even see a new form of inclusive economics develop, exciting the public and challenging its perception as the ‘dismal science’.

Nick is Director at PwC's Government & Public Services practice.

Related articles

-

Tackling populism through practical inclusion

Megan Corton Scott

In the current populist era an active initiative such as the Citizen’s Economic Council is not only necessary, but a breath of fresh air argues Megan Corton Scott.

-

Why we need to reform economics education

Maeve Cohen

Maeve Cohen, Director of Rethinking Economics, discusses why the Citizens' Economic Council report should recommend a reform of economics education.

-

Two kinds of Budget, one kind of Chancellor?

Reema Patel

Reema Patel introduces two kinds of Budget - the 'u-turn' Budget, or the frozen Budget. Might there be a way forward through this impasse for a bigger, more collaborative conversation about economic questions?

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Would we need citizens' juries (aka focus groups) if our political leadership was properly representative? That is to say, if our politicians were wholly nominated from, and elected within, identified communities -- as opposed to being selected by minority (external) interested parties (the party politic) and allocated to a community -- wouldn't the voice of the community have a greater opportunity to be heard with legitimacy?