The Citizens’ Economic Council programme publishes its final report: ‘Building a Public Culture of Economics’ today. It makes the case for deliberative approaches to democracy being adopted alongside current representative and direct forms of democracy – arguing that the process of ‘doing’ democracy is crucial in securing fairer economic outcomes and thereby building democratic legitimacy.

The outcomes of economic policymaking

Last month, the Citizens’ Economic Council programme team hosted a roundtable to discuss what democratic innovations could do to promote democratic legitimacy. One attendee challenged us suggesting that the decline in democratic legitimacy and consequent rise in populism is not due to democratic processes, but rather due to the economic outcomes that current policy is creating.

They argued that people are fed up. Fed-up of the inequality, of being left behind, of being unheard. That people are fed up of the outcomes of economic policy and do not necessarily care about the process by which these outcomes have arisen.

Indeed, the 2017 Social Mobility Report paints a picture of a country divided. It examines England’s 324 local authority areas and ranks them using indicators that measure education, employment and housing prospects of people in that area. Hotspots on the index are where people from disadvantaged backgrounds are most likely to make social progress and coldspots are where there is least chance of mobility. The division is between London and its commuter belt, and the rest of the country. Although London does contain pockets of high deprivation, overall it has almost two thirds of the country’s hotspots, whereas the coldspots feature predominately in rural or coastal and deindustrialised areas. Where someone is born and brought up in the UK dictates how well they will do in life more than their individual merit or capability.

The RSA agrees that these aren’t the outcomes we’d like to see from economic policymaking – ideally we want a far more inclusive economy which allows individuals to succeed regardless of where they live in the UK. This calls into question the process by which these outcomes were created.

Is the process of policymaking important?

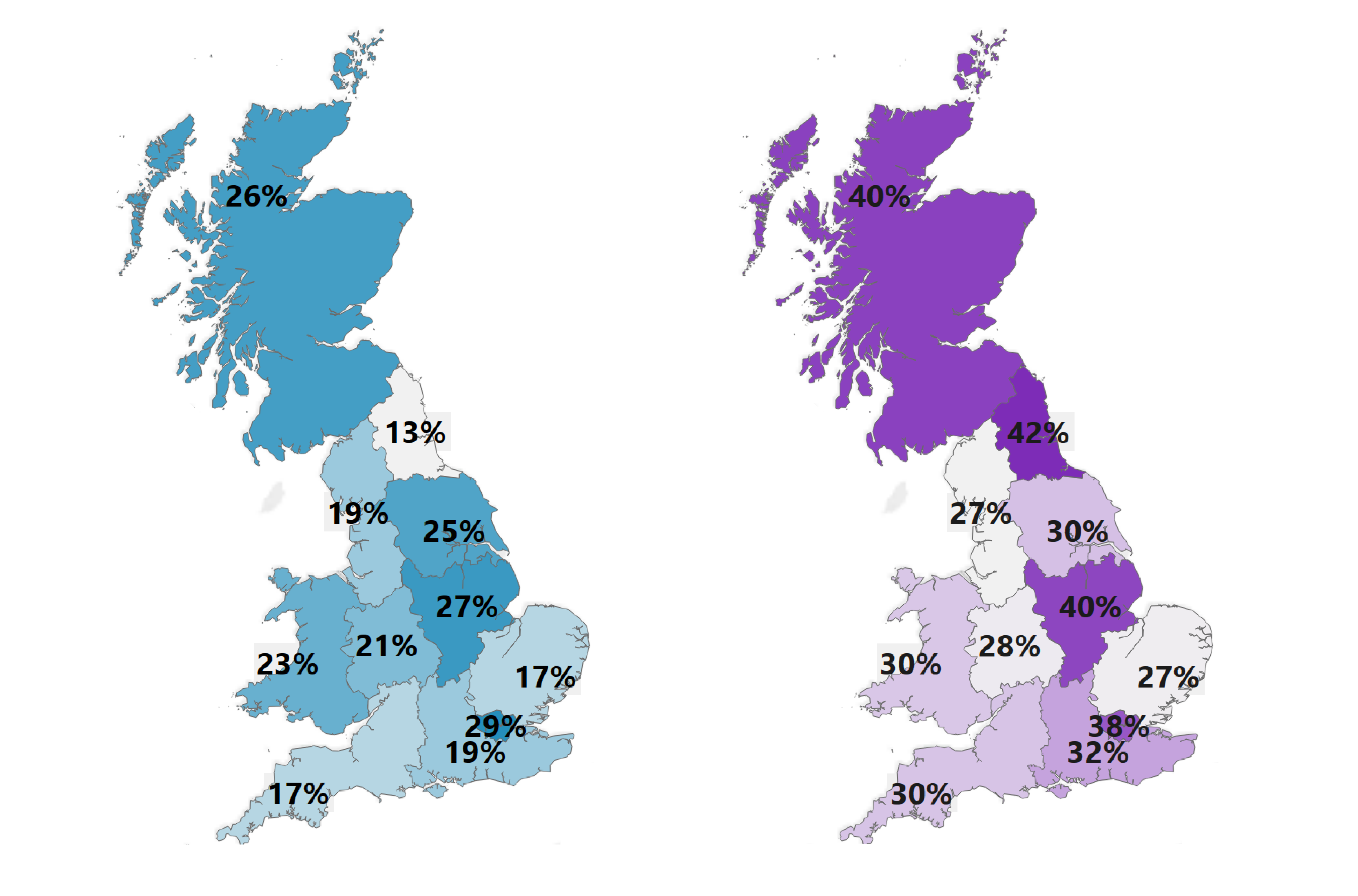

As a recent Populus poll we commissioned shows, there is also regional variation in peoples’ sense of influence over the processes by which economic decisions are made. For example, residents in the North East reported the most influence in the UK over local councils (42%) but the least over central government (13%). Compare that to London where the difference in levels of influence over local councils and central government is much smaller, with 38% reported influence over local councils and 29% over central government. This indicates the importance of distance to and sense of familiarity with economic decision-making bodies, and citizens’ sense of participation and ability to influence the economy. One of the recommendations we make in our report is that ‘double devolution’ to local bodies and citizens could help bridge this gap.

Citizen sense of influence over central government (left) vs local councils (right)

Building a public culture of economics

As our report suggests, we need to ‘build a public culture of economics’ in which diverse citizen voices can be included in and have influence over economic decision-making so that outcomes are reflective of the needs of people across the country. We contend that the process of deliberation, where citizens exchange arguments and consider different claims that are designed to secure the public good, could be a way by which to do this – adding to democratic structures that already exist and strengthening the democratic management of our economy.

We argue that the process (good public engagement) in itself creates 3 outcomes:

-

Agency – participation, when done well, builds human capacity and active citizenship. This has intrinsic value in contributing to the pursuit of fulfilling lives and respecting human rights. It also has instrumental value in contributing to the other two outcomes.

-

Legitimacy – gaining the explicit and implicit consent of the governed for both the goals of economic policies and institutions, and the means by which these goals are pursued.

-

Efficacy – helping economic policy and institutions to be more effective in delivering such legitimately determined outcomes.

This is not to say everything is perfect in the realm of deliberative democracy. There will still be winners and losers, but the process of ‘doing democracy’ differently may help to build the much needed trust in, and trustworthiness of, our political and economic institutions.

Read the final report ‘Building a Public Culture of Economics’to find out our recommendations on how we can start to do this.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

I don't perceive any extraordinary among these terms. It basicallywholes up the parts of human rights that we need to perceive in our generalpublic since we as a whole are taking part in these perspectives except forsocial standards that characterize gender orientation role.<a href="https://www.dissertationempire.co.uk/">Dissertation Writing Service</a>