As devotees of Lord of the Rings will know, when the Eye of Sauron turns its gaze on you, you had better beware. In similar fashion, the past six months or so have seen an unprecedented growth of parliamentary and departmental interest in school exclusions and in the small world of alternative provision (AP).

‘AP’ describes a type of school, including Pupil Referral Units (PRUs), that provide an education for children who do not have a mainstream or special school place, usually as a result of permanent exclusion but the sector also caters for children referred to it for behavioural reasons and others with medical needs, including mental health. Places in AP are commissioned by local authorities and, to a lesser extent, schools. It is a small sector but, with exclusions on the rise, it is growing in numbers of children if not in capacity.

There is much to discuss in this area, not least the real reasons behind the alarming rates at which children are being excluded. But, in this blog, I want to discuss the worrying implication being made by legislators and commentators, people not directly involved in AP, that the sector is letting down the children who, following exclusion, find themselves in their care. Some providers, in some areas of the country, probably are letting them down; the majority are not. Indeed, PRUs and AP academies are averaging better judgements from Ofsted than mainstream schools. The problem here lies in the nature of the yardsticks being applied.

AP in the spotlight

Kick-started, I suspect, by the publication of Kiran Gill’s excellent report, Making the Difference, and after years of little promise and no action, we suddenly have an inquiry by Parliament’s Education Select Committee; a DfE review of exclusions, led by former MP Edward Timpson; and two DfE-commissioned research projects (research into Alternative Provision by IFF Research and Alternative Provision Market Analysis by ISOS ). Alongside this official look at exclusions and AP, the press and researchers are also showing more interest. I am very pleased that the RSA is engaging in this issue as well (see Pinball Kids: Working Together to Reduce School Exclusions).

One can only assume that such a level of political interest will lead to rules being changed or new ones being created. I obviously hope that such change will be based on a deep understanding of the sector; but, as someone with considerable experience in AP, I do worry about the extent to which this is the case.

In his initial call for evidence, Robert Halfon MP, Chair of the Education Select Committee, wrote: “Students in alternative provision are far less likely to achieve good exam results, find well-paid jobs or go on to further study. Only around 1% of young people in state alternative provision receive five good GCSEs.” He is not wrong; outcomes in AP are a long way below those in mainstream education. And he is not alone; one can hardly read about AP without one’s attention being drawn to this:

“The academic outcomes for pupils who go into AP and PRUs are poor.” [Improving Alternative Provision (‘The Taylor Report’), DfE 2012]

“Currently only 1 per cent of excluded pupils get the five good GCSEs they need to access the workforce.” [Making the Difference, IPPR, 2017]

“National data shows that 4.5% of children who attended AP achieved 9-4 passes in English and mathematics at GCSE, compared to 65.1% in state-funded mainstream schools”. [Creating Opportunity for All, DfE, March 2018]

“Just one per cent of excluded pupils receive five passes at GCSE including English and Maths.” [Laura McInerney, Schools Week, May 4th 2018]

Without exception, the authors of these reports duly qualify the facts with what reads like the rare exception. For example, in Creating Opportunity for All, we read: “Many children are supported to make rapid social, emotional and educational progress whilst in AP settings ...” Predictably enough, though, the author’s next word is “but”.

Is this a level playing field?

So, “students in alternative provision are far less likely to achieve good exam results”. Yes, this is irrefutably the case. But it would make much more sense to invert Mr Halfon’s phrase thus: students who are less likely to achieve good exam results are far more likely to find themselves in alternative provision.

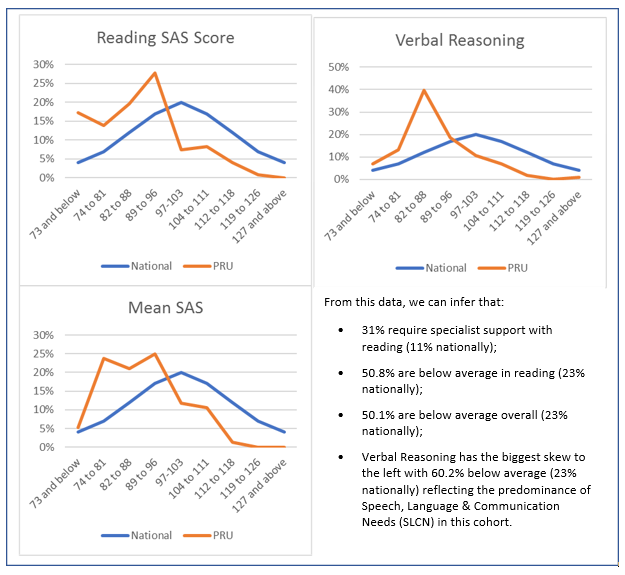

As the head of a large PRU, I collected data on the ability levels of students being admitted. The following graphs show standardised scores of newly arrived students in key stage 4 at the PRU in 2016 compared with national norms. The evidence clearly shows that, while pupils are nearly always referred to AP because of their behaviour, the clear majority of them are also significantly disadvantaged, or behind, in their learning.

At the same PRU, in preparation for an Ofsted visit, I wanted to collate evidence for what I knew to be the case, i.e. that young people at the PRU were making accelerated progress with us when compared to their time in mainstream school. The often chaotic and disrupted lives of these young people meant that I was only able to find data for 56% (c. 50 children) of the Y11 cohort I was researching. What I found was that in their mainstream schools, this group had on average made negative progress in key stage 3. These children find themselves in AP, not because schools have been unable to manage or modify their behaviour – that is secondary – but, primarily, because they have not engaged them in their learning.

It follows logically that children who have almost never experienced success or praise disengage from learning, leading them into behaviours that results in either a referral into AP or permanent exclusion. The first job AP must do for a new child is almost always to work to re-engage the child and to reveal to them what it feels like to succeed. Those of you who work in AP will, like me, have lost count long ago of the number of times a parent or child has said, “I never would have done so well back in *Blank School*”.

What do appropriate measures of success look like?

It is unfair then to use the same yardstick to judge both AP and mainstream schools and then to use the stark difference between them to imply that AP is substandard.

Using performance measures like ‘good GCSEs’ as comparators makes little sense and I urge policy-makers to consider others that are more relevant. Students at my PRU - and many others – left at age 16 with valid qualifications that do not count towards institutional accountability measures and so are rarely offered in mainstream schools. These include workplace qualifications from the likes of City & Guilds, functional skills in English and Maths, and personal development accreditations like the excellent Achieve programme from the Prince’s Trust. Can these not be considered? Other examples of more relevant indicators of the success or otherwise of AP could be NEET figures, numbers of returns to mainstream education, confirmed post-16 destinations and progress in numeracy and literacy. There are even tools, like the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale, which can quantify and thus enable the tracking of changes in children’s wellbeing

PRUs and AP schools serve a distinct population from mainstream schools with their own set of needs. Therefore, they should not be judged by the same measures, whether by Ofsted, politicians, the DfE, researchers or commentators. Now would be the right time to think about and develop relevant standardised performance measures for AP before changing the rules that govern it.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

This is a great article and as a principal of an AP performing arts and creative media college I wholeheartedly agree with John that there needs to be different measures of success for these kind of settings.

http://www.wacartscollege.co.uk/

Hi James,

I think you are the Principal of the AP where my daughter works- Isabel Alsina Reynolds.

I’m Principal of Frome College, a year 9-13 upper school in Somerset. There’s no AP here for miles around and I need to develop some funding mechanism plus manage staff understanding of AP to get things going. Izzy mentioned you may open to a visit one school day? I’d like my SLT lead to see different options for AP and your school looks great.

Let me know what if this sounds ok- naturally we could offer a reciprocal visit/ project work.

Have a lovely summer

Emma Reynolds