Today, you might associate East London with buying clothes rather than making them. Or perhaps design comes to mind, and the many creatives who base themselves in and around Shoreditch. Where once the area would have thronged – and stank - with the sector’s many factories and dye houses, today you could be forgiven for thinking that all remnants of the garment industry are long gone. However, whilst the sector has undergone dramatic changes in the last fifty years, the area remains important for textile and garment making today. And new trends and technology are pointing to the ways in which this sector will be part of Londoners’ lives in the future.

The rag trade was a thriving part of the city’s economy in the 19th and 20th centuries, and the Lower Lea Valley in the East of the city was at the heart of this industry. As manufacturing has become an increasingly globalised industry – chasing the cheap needle around the world – the sector has declined significantly in London and the UK. Today most production takes place overseas and you are significantly more likely to find a ‘made in China’ label in your top than ‘made in Britain’, let alone London.

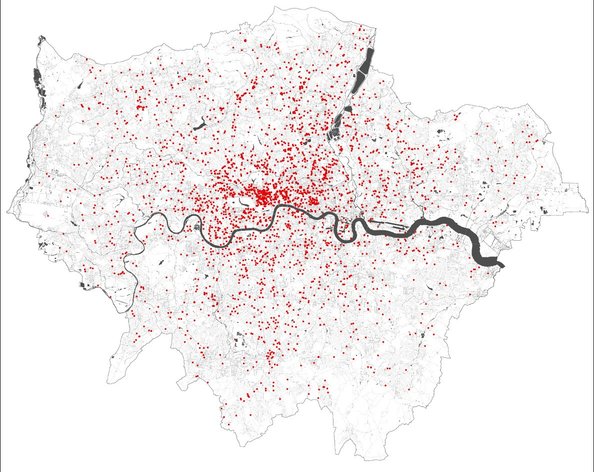

But all is not gone; the manufacturing of ‘wearing apparel’, as it is categorised, remains an important part of London’s manufacturing base, contributing £800m to the city’s economy each year. It provides employment for over 10,500 people in the capital, which is 1 in 5 of all UK garment workers, and non-garment textile production employs another 3,000. These producers can be found all across the city as this map from our recent Cities of Making report shows.

Map: Each dot represents an individual business registered with the NACE code related to wearing apparel.

Source: ORBIS database Created by: Birgit Hausleitner

Fashion centre

London is, after all, a fashion capital. Its bi-yearly celebration, London Fashion Week, attracts over five thousand movers and shakers from the fashion world. Whilst the focus is often on the designers, the manufacturers in the city who bring the creations to life should also be celebrated.

One of these companies, The Albion Knitting Co. in Haringey, was established in 2014 and is the first industrial scale flat knitting factory to open in London since the war. Their parent company, Alphatex, is a Beijing based manufacturer owned by Chris Murphy, who moved to China two decades ago as part of the knitwear sector’s shift to the Far East. He and his co-founder opened Albion in order to be close to their clients in Europe’s luxury fashion houses.

Nearby Kashket & Partners take bespoke production even further. They are currently the exclusive supplier of ceremonial military garments to the Ministry of Defence, with their team of highly skilled tailors and artisans producing and servicing uniforms for regiments including the Household Cavalry. You might well have seen the uniforms they made by hand for their Royal Highness's Princes William and Harry for the Royal Wedding in 2011. Their uniforms for this year’s big day were made by another London tailor, Dege & Skinner of Saville Row.

It’s perhaps more surprising to hear that manufacturing for fast fashion brands also takes place in the city. Fashion Enter, based just around the corner from Albion, supply e-commerce giant ASOS with womenswear; a signal that mass production brands are also interested in the made in London cachet. Fashion Enter’s machinists produce up to seven and half thousand units a week, and this social enterprise also offers a range of learning and apprenticeship opportunities for would-be designers and makers.

Sustainable innovation: making it better

In the late 1800s many factories moved over the river to West Ham to avoid growing environmental regulation in London. Dye works, oil cloth producers, tanneries were all to be found in the area. We saw a glimpse of the environmental impact of this industry in the run up to the Olympic Games when nearly two million tonnes of soil on the site was ‘washed’ to remove contaminants. No doubt the area’s textile production history contributed to this pollution.

Textiles continues to be one of the most polluting sectors in the world: its large carbon footprint, its pollution of water and soil, its large consumption of pesticides and other chemicals make it second only to oil in terms of its environmental damage. And this is to say nothing of the social impacts of this destruction, or the working conditions of those employed in the sector. In London we rarely see this on our doorstep, we have exported the issues to other parts of the world. The pressing challenge we now face is to find ways of making and using textiles which do not endanger the environment and the lives of people in any community.

Kniterate, an East London based start-up, have an innovation which could contribute. They have developed an affordable compact digital knitting machine which allows designers to make digitally enabled designs on a small scale in their workspaces. Until now this was only possible with industrial knitting machines, which cost upwards of £35,000, take up a lot of space and require a technician to operate. Newly developing technologies like these are showing the potential for more smaller scale production within the city. Whereas previous revolutions led to manufacturing becoming centralised, it is now being redistributed, back into the hands of local makers.

Textile futures in the Lea Valley

The textile and garment industry in the Lea Valley is almost unrecognisable from a century and a half ago, but the sector is alive in the area, and new trends and technology are opening up opportunities for the area’s makers and manufacturers. London College of Fashion will move into the Olympic Park site in the next few years, along with a host of other cultural institutions, bringing with them a new generation of designers.

However, there are challenges to overcome. As the UK prepares to leave the European Union there are concerns in the industry about staffing because an estimated 70% of London’s garment manufacturing workforce are from elsewhere in the EU. This is because fewer people in the capital, and the UK more widely, have the skills required. As the industry has shifted overseas we have lost the skills base, and a career in manufacturing has come to be seen as less attractive than it once was. Albion Knit have had to deal with the issue of skills. In the 1990s UK staff went to China to train workers there, today Albion bring staff from the Chinese arm of their business to help train up local workers. However, they, along with Fashion Enter and others are developing new skilled workers and re-establishing the profession in the city. And as interest in craft and making undergoes a revival, there is optimism that more Londoners may wish to move into the sector.

Space to make is also an issue. London has lost a significant amount of its industrial land over the last fifteen years. Space equivalent to around 1800 football pitches has been transferred into use for housing and other business activities. Many of the areas greatest industrial hubs around the lower Lea Valley, like Hackney Wick, have been greatly affected. As London develops authorities need to find ways of accommodating its productive activities as well as its residents.

London has a strong heritage of textile and clothing production. Today the city should be as proud of its manufacturers as its designers, and support the next phase of its life in the city.

Text edited from original piece written for 'Raw Materials: Textiles', an exhibition about the textile industry in East London at Bow Arts.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.