AI is increasingly being used to help make important decisions in a range of domains, from the workplace to the criminal justice system. Yet, few people are aware of AI’s role in decision-making, and opposition to it is strong. Why are people concerned, and what, if anything, would make the public more comfortable with this use of AI?

Our new report, launched today, argues that the public needs to be engaged early and more deeply in the use of AI if it is to be ethical. One reason why is because there is a real risk that if people feel like decisions about how technology is used are increasingly beyond their control, they may resist innovation, even if this means they could lose out on benefits.

This could be the case with automated decision systems, which are on the rise. Automated decision systems refer to the computer systems that either inform or make a decision on a course of action to pursue about an individual or business. To be clear, automated decision systems do not always use AI, but increasingly draw on the technology as machine learning algorithms can substantially improve the accuracy of predictions. These systems have been used in the private sector for years (for example, to inform decisions about granting loans and managing recruitment and retention of staff), and now many public bodies in the UK are exploring and experimenting with their use to make decisions regarding planning and managing new infrastructure; reducing tax fraud; rating the performance of schools and hospitals; deploying policing resources, and minimising the risk of reoffending. The systems have been characterised as ‘low-hanging fruit’ for government and we anticipate more efforts to embed them in future.

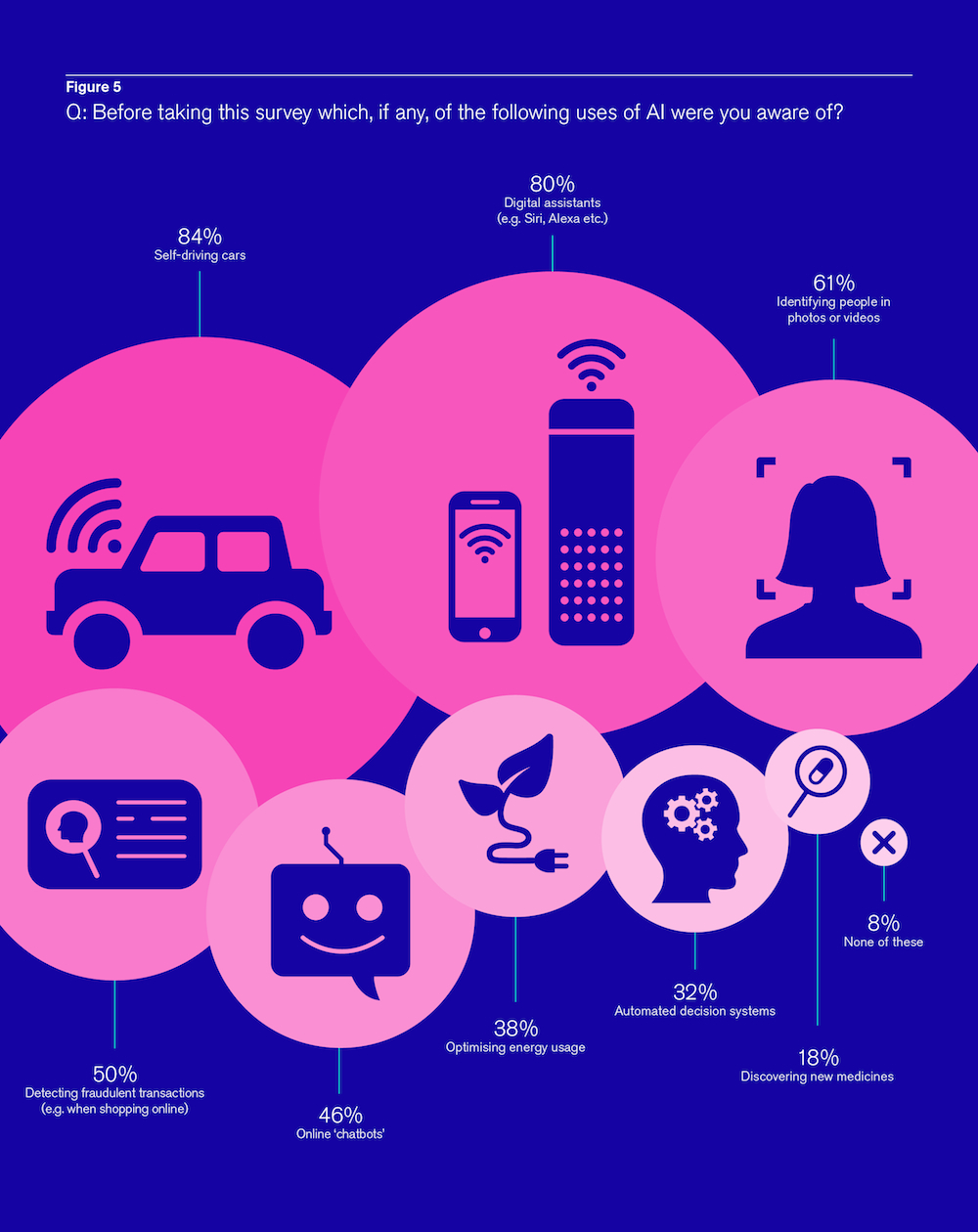

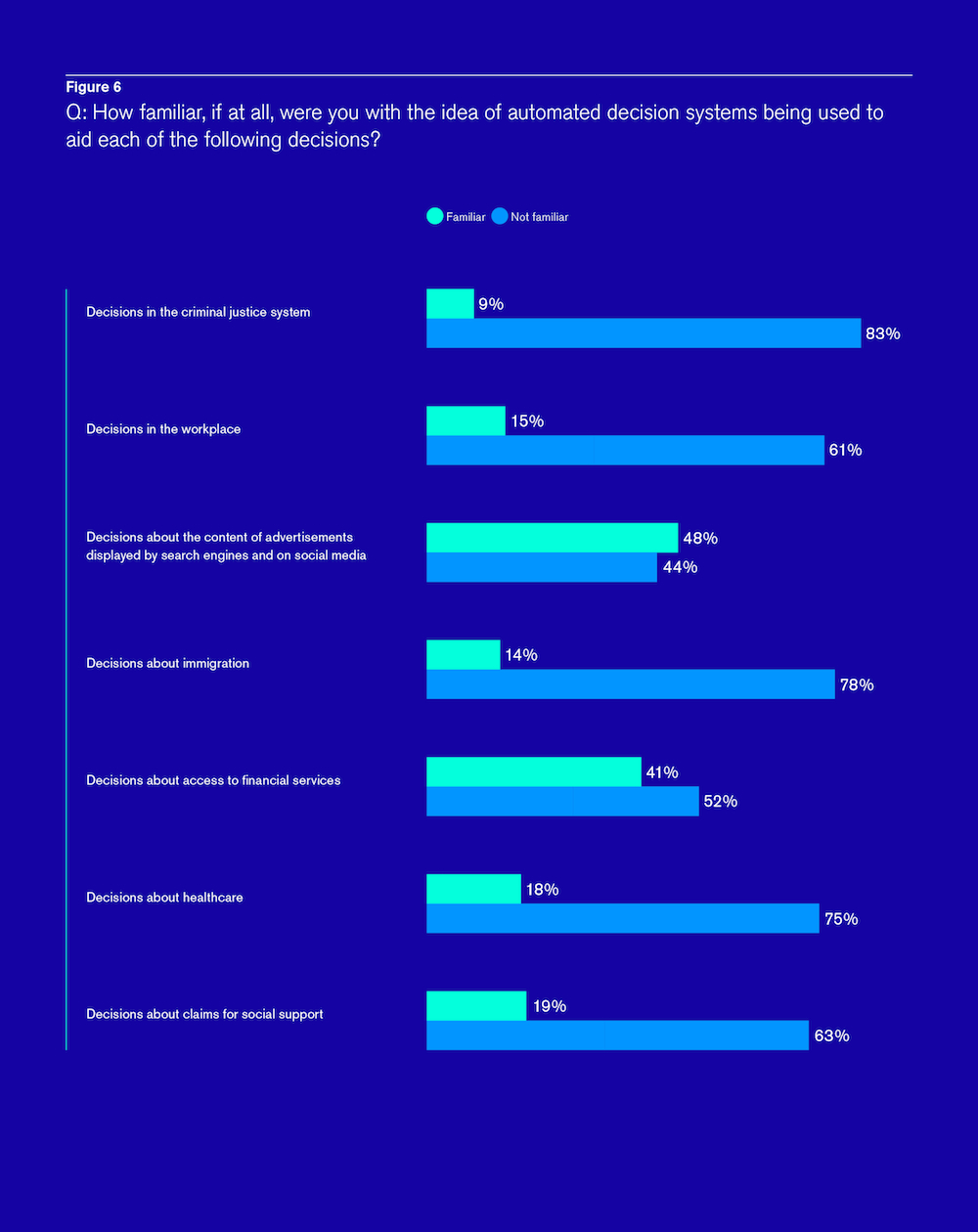

However, from our online survey of the UK population, carried out in partnership with YouGov, we know that most people aren’t aware that automated decision systems are being used in these various ways, let alone involved in the process of rolling out or scrutinising these systems. Only 32 percent of people are aware that AI is being used for decision-making in general.

This drops to 14 percent and nine percent respectively when it comes to awareness of the use of automated decision systems in the workplace and in the criminal justice system.

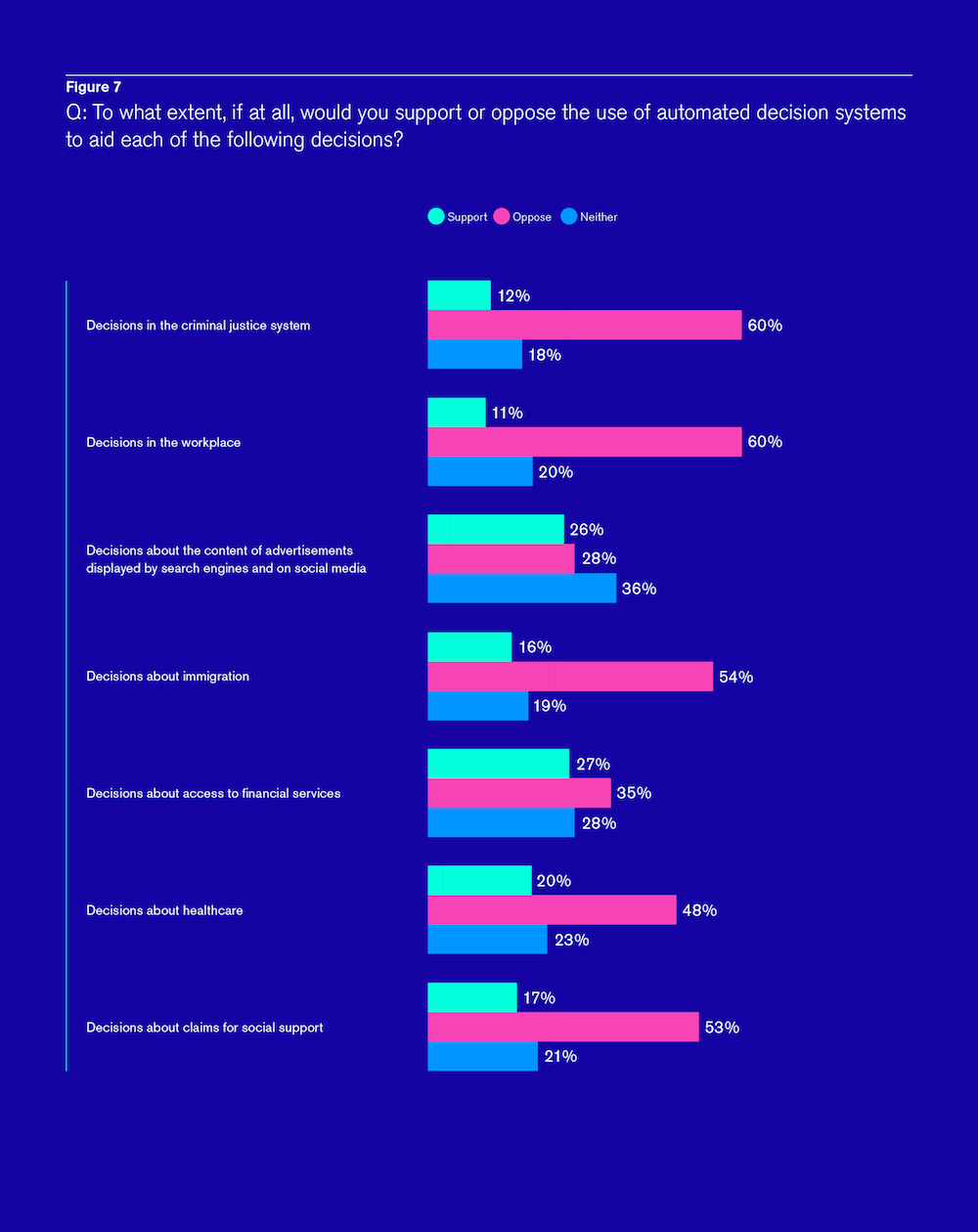

On the whole, people aren’t supportive of the idea of using AI for decision-making, and they feel especially strongly about the use of automated decision systems in the workplace and in the criminal justice system (60 percent of people oppose or strongly oppose its use in these areas).

To learn more about the reasons for their lack of support, we asked people about what most concerned them about these systems. They were asked to pick their top two concerns from a list of options. Although we made it clear within the question that automated decision systems are currently only informing human decisions, there was still a high degree of concern about AI’s lack of emotional intelligence. Sixty-one percent expressed concern with the use of automated decision systems because they believe that AI does not have the empathy or compassion required to make important decisions that affect individuals or communities. Nearly a third (31 percent) worry that AI reduces the responsibility and accountability of others for the decisions they implement.

This gets to the crux of people’s fears about AI – there is a perception that we may be ceding too much power to AI, regardless of the reality. The public’s concerns seem to echo that of the academic Virginia Eubanks, who argues that the fundamental problem with these systems is that they enable the ethical distance needed “to make inhuman choices about who gets food and who starves, who has housing and who remains homeless, whose family stays together and whose is broken up by the state.”

Yet, these systems also have the potential to increase the fairness of outcomes if they are able to improve accuracy and minimise biases. They may also increase efficiency and savings for both the organisation that deploys the systems, as well as the people subject to the decision.

These are the sorts of trade-offs that a public dialogue, and in particular, a long-form deliberative process like a citizens’ jury, can address. The RSA is holding a citizens’ jury because we believe that when it comes to controversial uses of AI, the public’s views and, crucially, their values can help steer governance in the best interests of society. We want the citizens to help determine under what conditions, if any, the use of automated decision systems is appropriate.

These sorts of decisions about technology shouldn’t be left up to the state or corporates alone, but rather should be made with the public. Citizen voice should be embedded in ethical AI.

This project is being run in partnership with DeepMind’s Ethics and Society programme, which is exploring the real-world impacts of AI.

Our citizens’ jury will explore key issues that raise a number of ethical questions including, but not limited to, ownership over data and intellectual property, privacy, agency, accountability and fairness. You can learn more about our process in the report.

-

Download the report - Artificial Intelligence: real public engagement (PDF, 1 MB)

-

Check out the story our survey data tells and explore findings using Flourish

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

We're actively working both sides of AI: how machine perception can help people with disabilities (reading machines, etc.) and human rights (sifting through millions of videos to find the right ones for investigators to look at) as well as the negative aspects, such as the near-certainty that increased use of machine learning in recruiting is discriminating against people with disabilities in employment.

Thank you, Brhmie, for all your work on this important issue.

Several media articles abotu this report mention the well-known catchphrase from Little Britain, "computer says no". There is a perception that automated decisions do not take account of special circumstances. In financial services, where I work, there is some truth in this, partly as a side-effect of the Treating Customers Fairly principles that regulators require the industry to follow. If one customer is told "no" while another in the same situation argues special circumstances and gets a "no" turned into a "yes", the first customer could argue that they have not been treated fairly. Financial services providers wanting to avoid this may employ strict tick-box criteria so that everyone ticking the right boxes gets a "yes".

Tick-box criteria are more reminiscent of an older version of AI, rules-based systems, which were popular years ago when I did my masters in the subject. Although perhaps annoying and seemingly arbitrary at times, they do have the advantage that if the computer says "no", it should be relatively straightforward to identify which criteria are not met, and correct the answers if there are any errors.

What happens in a deep learning based decision-making system if it is discovered that some of the data used for the deep learning process is incorrect? If the deep learning process is re-run with corrected data and lots of decisions are wrong, I guess there could be a substantial claim for compensation.

Many decisions do not require any particular empathy, in fact sometimes any emotion is better left out of the equation, so there should be no problem with AI per-se, e.g. can an applicant afford to repay a loan or not. If they cannot, then it should not be granted and the risk parameters should be entirely at the funders prerogative (a whole other discussion perhaps). It seems to me however, that the real problems with designing any sort of automated process is firstly, deciding whether human judgement should be a factor or not and we often get this wrong. Secondly, is to create a design methodology which mitigates against the bounded rationality of the designer/s. This seems to be a huge obstacle, just take some of the perverse semi automated arrangements designed by some utility companies and Banks, which only succeed in making extra work and less satisfaction for customers. How often is your question or problem one they have correctly anticipated and allowed a solution for? Once launched, such over engineered systems are often very hard work to get changed due to other built-in design dependencies, sunk costs, or designer complacency.