Last week, the RSA US hosted a Future of Work Summit as part of the “New Mutualism” conference held in Pittsburgh. The occasion was an opportunity to hear first-hand from city leaders and stakeholders about how Pittsburgh became a stellar example of the post-industrial renaissance.

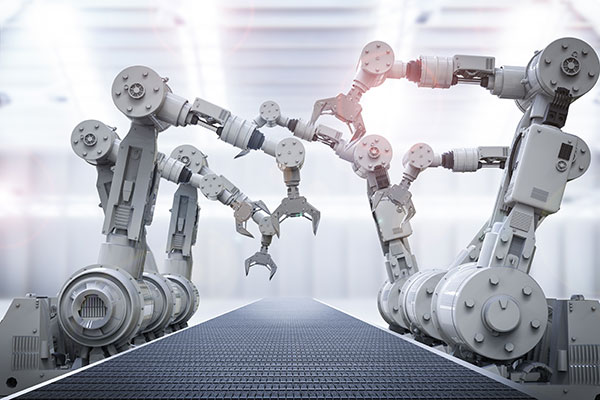

Pittsburgh emerged from the deindustrialisation of the 1980’s characterized by rapid closure of steel manufacturing plant, urban decay and depopulation to become the envy of the world as a hub of advanced manufacturing, robotics and artificial intelligence.

With such a vibrant tech hub, the city of Pittsburgh has attracted and retained high skilled talent cultivated by key anchor institutions such as Carnegie Mellon University and University of Pittsburgh creating an innovation district around advanced technology. There is no doubt that Pittsburgh has escaped the economic haze which once covered the city. However, one thing which emerged from the summit was that people of Pittsburgh were not content to simply rest on their laurels but were keen to address some of the intractable social challenges facing the city. These challenges include race and class inequities, entrenched poverty, health inequalities and a raging opioid crisis.

At the end of the summit I was left with two key takeaways 1) there is a direct conflict between the American ethos of individualism and the reality that a job is no longer enough to emerge from poverty and 2) without confronting the structural inequality facing certain communities the changing nature of work will leave many behind.

From the outset the Future of Work summit was not simply a nebulous talk shop about the changing nature of work but instead centred on the future of workers existing in this shifting environment.

Ben Dellot, Head of the RSA Future Work Centre, framed the central conceit of the summit at the very beginning by highlighting the importance of good work. He indicated that work is not an isolated objective but rather it is how a society creates security and opportunity for its citizens.

During the summit, many themes percolated throughout the day which included the concept of universal basic income, increasing the bargaining power of workers, and what worker voice looks like in the 21st century. However, the most interesting part for me was the palpable energy to address the elephant in the room - a reimagining of a new social contract i.e. what does it mean to be a worker in the 21st century? What are the unwritten rules that govern this society, and does it impede or expand opportunity and economic security for all? What is expected of government and what is expected of the individual?

As an outsider, it was interesting to learn from the lived experiences of my American colleagues. There was a definite sense among the summit attendees that they were grappling with the concept of individualism as the main artery of the American dream being challenged by the drivers of changing the nature of work and therefore leading the individual worker down a path of increasing precarity. This economic insecurity is further heightened in an environment where real wages for American workers are up a mere 3% since 1979.[1]

At the RSA we conceive the changing nature of work as an opportunity to adopt radical technologies on our own terms aimed at expanding opportunity and enabling each individual to reach their highest potential. Admittedly this is difficult to consider when there are barriers to opportunity which may obscure this view. For example, two recent articles published by the New York Times really illustrated this point. One was centred on the steelworker in Indianapolis and another, a care worker based in New Jersey. Both at different ends of the spectrum, one highly skilled well paid, the other less skilled, with low pay and little opportunity for job progression. Both experienced the splintering effects of the changing nature of work in our modern economy. Both care for a sick family member. Both are women.

The more we fail to account for care as unpaid work the more we will continue to erect barriers for care givers - particularly single women - to expand their economic opportunity and reach their highest potential.

Similarly, another key concern which emerged during the summit that is not dissimilar to other cities, is how to ensure that the economic gains from a vibrant economic sector are accrued to everyone and not benefit a select few. This is especially potent for those from ethnic minority groups who face structural inequality which limits their ability to access better paying jobs and consequently economic opportunity. These endemic issues are further exacerbated with the advent of automation. According to the Joint Centre for Political and Economic Studies, “automation will have a significant effect on African American and Latino workers. Over 31 percent of Latino workers and 27 percent of African American workers are concentrated in just 30 occupations at high-risk to automation.”

In a previous blog, I wrote about how the drivers of the changing nature of work intersect at the global level, creating challenges for governments all over the world. If we view these drivers through the lens of a city the same thing occurs except it is more immediate and potent. In my view this is at the heart of the matter. Work is personal. It is what connects us to the wider society. It is also what frames our lived experiences as citizens. So, the effects of technology, globalization and changing demographics on work ultimately influence the stories we tell about ourselves and each other. What we will accept and what we will not accept. Therefore, if we fail to address the existing structural barriers to opportunity and the wider impact of technology on the nature of work, it risks fuelling the malaise and toxic politics within our society that is now commonplace today.

Despite this outlook, we ought to remain optimistic because there is an inherent dynamism which exists at the city level that creates an environment for these challenges to be addressed with a degree of urgency. In the context of Pittsburgh, its historical legacy has given the city the tools required to address the challenges. Pittsburgh’s historical legacy sets up this dichotomy between the individualism and collectivism quite well. In the 19th Century, it was the home to the titans of industry such as Mellon, Carnegie, Heinz who are embedded in the American psyche and mythology. It was also at the epicentre of the emergence of US organized labour movement since the 1887.

It is against this backdrop that the city has undergone several visioning processes that sought to connect economic growth to social development and environmental sustainability through a call to partnership with civic actors, private and public-sector agencies for the benefit of all. Most recently, the city has developed its P4 project evaluation framework which places people at the top of its criteria. At the close of the summit, it felt like the city was at another pivot point in its history.

Now, the city of Pittsburgh stands at the epicentre of advanced manufacturing technology, development of autonomous vehicles, robotics and artificial intelligence. All of which are contributing to the changing nature of work in the coming decades. Simultaneously the current administration appears committed to ensuring that everyone benefits from its transformation and growth. I for one hope Pittsburgh succeeds, and that it continues to be a model of how post-industrial cities can confront societal challenges with gusto and ambition that others can look to and replicate.

[1] Council on Foreign Relations The Work Ahead – Machines, Skills and US Leadership in the 21st century Pg. 7

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.