Government spends more than £250bn of taxpayers money every year, providing services, fixing problems or improving communities up and down the land. The risks of getting it wrong are high profile, destructive and far reaching. The benefits of getting it right include improved quality of life, innovation and value for money. In this two-part blog series I look at what happens when we apply the RSA’s model of change to help improve commissioning and drive innovation in public services - why do we often get it so wrong, and what are some commissioners doing to get it right?

In The Art of the Possible in Public Procurement, Villeneuve-Smith and Blake observe that “for all of this desire amongst Commissioners to think afresh, there can be a countervailing force… That barrier is often perceived to be procurement – with regulations and iron-bound processes acting to stifle reform, hamper innovation and maintain the status quo”. Such blind maintenance of the status quo in the face of compelling evidence for change is our definition of the ‘immune response to change’ in action. This is the “computer says no” mindset, of overbearing bureaucratic processes crowding out common sense. In recent work we have been exploring this notion - reasons why things can’t or shouldn’t happen, whether or not they makes sense.

Yet sometimes the immune response activates with good cause to ensure our organisations and systems remain healthy: the need to safeguard lives, spend public funds without any impropriety, avoid career-limiting mistakes that are likely to play out publicly, to prevent fraud and corruption. The irony is that processes intended to manage risk have been exposed by the collapse of Carillion, bearing as it did almost £7bn of liabilities - the largest trade insolvency in UK history. The very risk that the ‘immune response’ was trying to protect against still materialised.

We need a rethink, a new way of doing things that leverages the best of the present and introduces innovative practice alongside this. Such an approach would enable flexible and responsive investment in a proble. It would incorporate a much wider range of perspectives on a problem - from those affected by it - residents in the community, perhaps - to those with ideas that might address it.

In our recent work with CivTech in Scotland, the UK Government's GovTech challenge process, the Innovation Lab in Northern Ireland and others we saw the components of such an approach. In particular, we see that risk can mitigated by a range of measures, such as engaging users and beneficiaries in understanding the problem; having break points at each stage of the process; investing in early stage concept development. Collectively these provide assurances at each stage of the process. We can’t ask our commissioners to be solution experts but we can ask them to be problem experts.

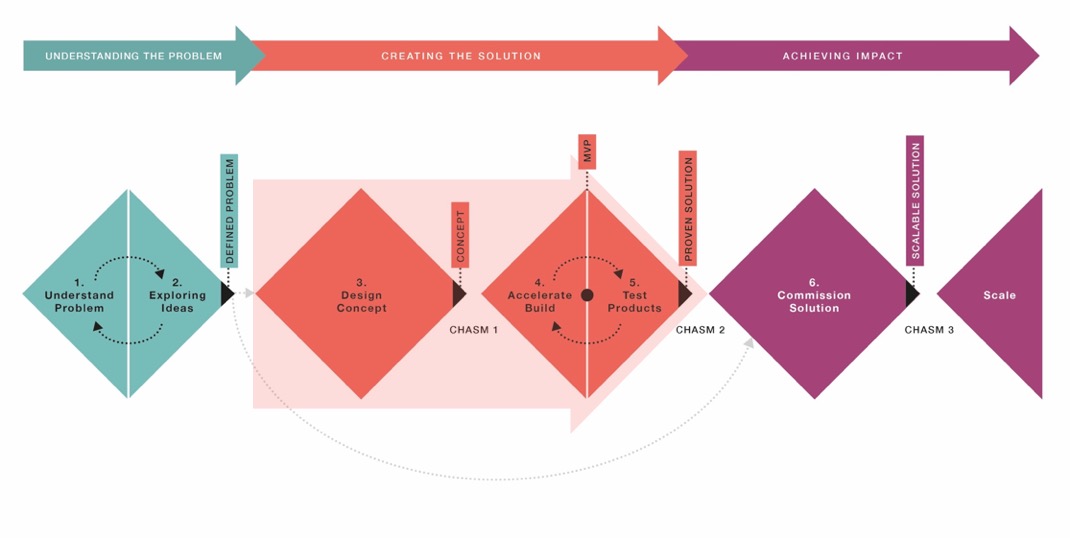

These insights, and others, were captured in a framework we published in our report ‘Move Fast and Fix Things’. This ‘invest to solve’ framework was the result of applying our ‘think like a system, act like an entrepreneur’ model of change to identify opportunities to try new ways of commissioning:

To summarise, it starts with the need to deeply understand the problem at hand, informed by those who stand to benefit (or who are affected) as well as potential solution providers. Following the problem definition, a 'make or buy' decision is reached. If the preferred route is to build (or work on) a solution collaboratively with a provider or providers, an iterative design, build and test approach is followed. Break points in the process allow financial and reputational risk to be managed as well as allowing for emergent learning and insight to be accommodated. Finally, a solution can be commissioned and, particularly for new market entrants or new solutions that have been developed and prove effective, scaled.

To summarise, it starts with the need to deeply understand the problem at hand, informed by those who stand to benefit (or who are affected) as well as potential solution providers. Following the problem definition, a 'make or buy' decision is reached. If the preferred route is to build (or work on) a solution collaboratively with a provider or providers, an iterative design, build and test approach is followed. Break points in the process allow financial and reputational risk to be managed as well as allowing for emergent learning and insight to be accommodated. Finally, a solution can be commissioned and, particularly for new market entrants or new solutions that have been developed and prove effective, scaled.

Thinking and behaving entrepreneurially in public services is anathema to most. But our conception of the ‘entrepreneur’ in the public sector is about judicious and not ubiquitous risk-taking. It’s about acting flexibility, seeking and harnessing the opportunity for change, working to overcome the barriers highlighted above through a flexible process. In addressing complex challenges, we need to iterate our way towards a solution, each step informing the next through learning and reflection.

As we have seen, this is a far cry from the dry and static specifications against which a path dependent procurement process is subsequently managed. We can’t expect our commissioners to downplay risk and value for money; indeed, we want them to care about these things more than ever. But we do need to find new ways of mitigating risk that enable an appropriate level of experimentation in complex scenarios, one that is based on a much more nuanced definition of risk.

Our next step is to test this framework in live contexts in localities and develop it over the coming months as part of our Public Entrepreneur programme. Please get in touch if you would like to work with us on this.

Ian Burbidge is an Associate Director in the RSA's Public Services and Communities Team. Follow him on Twitter @ianburbidge

Related articles

-

Open RSA knowledge standards

Alessandra Tombazzi Tom Kenyon

After investigating ‘knowledge commons’, we're introducing our open RSA standards and what they mean for our practice, products and processes.

-

RSA Catalyst Awards 2023: winners announced

Alexandra Brown

Learn about the 11 exciting innovation projects receiving RSA Catalyst funding in our 2023 awards.

-

Investment for inclusive and sustainable growth in cities

Anna Valero

Anna Valero highlights a decisive decade for addressing the UK’s longstanding productivity problems, large and persistent inequalities across and within regions, and delivering on net zero commitments.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.