Roger Harrabin, the BBC’s Environment and Energy Analyst, asked a Very Good Question on Twitter this weekend. “With big rise in CO2 expected, insectageddon, forest loss, plastics, soil loss etc, should we start referring to the environment as in global crisis – or will that scare everyone rigid?”

His replies mostly tended towards the “hell yes!” territory, with one topical reference to Greta Thunberg’s extraordinary speeches: "we cannot solve a crisis without treating it as a crisis, and we cannot treat it as a crisis without calling it a crisis.”

But there were a few in a different camp; “If you keep calling things a crisis, people will stop taking you seriously” citing the Millennium Bug and previous climate warmings to back their case.

My own contribution offered the (apocryphal) boiling frog metaphor, which says if you drop a frog into a pan of hot water, it will jump out. If you bring it slowly to the boil, it stays put – and dies. Humans are often slow to react to creeping existential threats.

So how does change happen? In the bookshop business sections, there’s arguably more written on change - alongside ‘leadership’ - than any other topic. Can we learn anything?

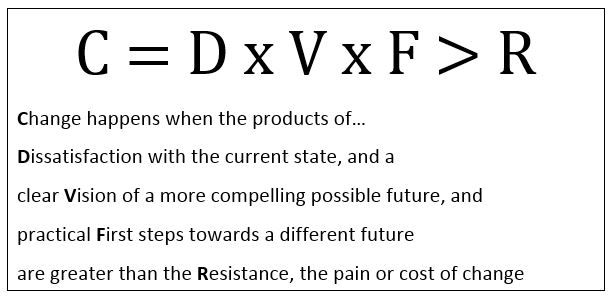

The Formula for Change was first developed by David Gleicher in the 1960s, developed further by Kathy Dannemiller, and popularised by Richard Beckhart and Reuben Harris in their 1977 book Organizational Transitions, and used many times since. It says this:

The important part of the equation is that little x. That multiplier means that if there’s a low or zero value in any of those components, the product will be low or zero. And the thing is this: with Britain more fractured and divided now than in years, and in the face of such overwhelming social challenges, we simply do not have a Common Formula for Change.

In spite of repeated warnings of the current crisis – climate breakdown, biodiversity loss, soil depletion – too many people are essentially content enough with what they’ve got. And that applies not just to those who are well protected against future shocks, through wealth, or resources, content with the whole panoply of advantage that comes with affluent western (or aspiring) society, but also those who have become fearful of losing what they have.

A new vision of the future, more attractive than the one we can currently imagine, is simply not well enough developed, let alone articulated. Too often, versions of the future are presented as a great loss, or risk of loss (“the immigrants are taking all your jobs!”), so much less than we might expect if we just carry on as we are. But what would a more equitable future look like, where people all over the world have enough of the resources they need to live healthy, contented, convivial, purposeful lives?

And then what? What are those first manageable, practical first steps we can each take, to get us from where we’re heading to where we prefer to be, sufficient to overcome the pain or the cost of change – which will inevitably generate psychological and practical resistance?

In the business change world, the Formula for Change has often been interpreted to mean: tell people why they can’t carry on as they are, sell them your vision of the future, and implement the project plan to get there – pressing hard enough to overcome their resistance to change, because “people don’t like change.” But this is exactly how change programmes in complex conditions fail.

In my experience, what I have found to be more helpful is to integrate psychology, sociology and critical approaches, to create the conditions in which people can connect the personal and the political (or the organisational) and work through their own personal formula for change.

To really understand both how dissatisfied and satisfied people are, with how things are, we need to not only tell it as we see it, but also hear clearly how others see their situation - through talking honestly, listening respectfully, empathising compassionately, with people outside of our usual ‘tribes’ and especially to those whose voices we rarely get to hear. People become more open to change when we feel heard, when our concerns are understood and considered.

Instead of selling visions - an approach which tends to benefit the clever orators, whether or not there’s any substance or honour behind their speeches - I prefer to talk about co-creating our version of the future, which is more inclusive, more attractive and more compelling to more people. This takes time. But if we’re all in the conversation together, it becomes a bit harder to just argue for what works for you, if it comes at the expense of others.

Then the first steps. And this is where all talk of grand strategies or big project plans fail us. When we’re co-creating a version of the future, it is nigh on impossible to draft the whole plan to get there, since the way ahead will be uncertain and unpredictable. Instead, we need to acknowledge this reality, and focus on the practical actions that move us forward, testing fresh possibilities, and working together in rapid cycles of observing and sensing, learning fast and adapting as we go.

This is work of the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission: convening new conversations and synthesizing knowledge and perspectives from many places across the UK.

The Commission’s devolved inquires have established their own programmes to consider questions that are relevant for them; research topics include better public procurement in Wales, citizen-led conversations around reconnection in Northern Ireland and questions around rural communities and food policy in Scotland. Locally-led inquiries in Cumbria, Devon and Lincolnshire cover a similarly wide-range of topics from the sustainable use of soil, to barriers to new entrants in farming and the relationship between landscape, food and farming. It is through working together that we can co-create versions of a better future and craft practical and radical strategies to help us all get there.

Sue Pritchard is Director of the Food, Farming & Countryside Commission

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

I have been using the term crisis for several years now, to refer to both the climate crisis and the ecological crisis. It’s simply speaking truth to truth, and I feel it’s dishonest not to do so.

Whenever I give talks on the climate crisis, I devote ten minutes to the crisis aspect, emphasizing just how bad it is, and the fifty minutes to vision, solutions, and practical next steps. I find this works really well.

You are quite right that there’s not yet a clear vision of a more compelling possible future. I responded to this first by spending three years writing a novel – Journey to the Future: A Better World is Possible (http://www.journeyto-thefuture.ca), and now by digging deeply into what’s going so wrong with our economy, and a book that I’m still researching and writing on The Economics of Kindness: The Birth of a New Cooperative Economy (http://www.thepracticalutopian.ca).

This summer, when the forest fires across British Columbia turned our skies yellow and the sun a strange orange disc, many people registered to what the world ‘crisis’ meant’ – they knew in their bones that something was going badly wrong, and though I can’t prove it, I think this lay behind a marked shift to more progressive people being elected to local office in our recent municipal elections, and for the climate crisis to figure often in their speeches.

I believe the lack of a positive vision is caused by a disconnect between the environment and the economy. When I ask environmentally-minded audiences if they know what quantitative easing, is for instance, scarcely a single hand goes up. If people don’t understand QE, how can they understand Green QE, or QE for the People? Likewise, although some people have begin to understand how money is created, no-one that I know understands that governments can choose to apply credit guidance as to the purposes for which money is create, by both banks and central banks. Similarly with “the market” – the economists have done such a good job of selling us their neoclassical nonsense over the past 120 years that people have been quietly brainwashed to believe that there are natural economic laws, and ‘the market’ is some kind of an autonomous thing, separated from the values and purpose which we choose to imbue in it.

A compelling vision must combine:

(a)a clear understanding that the world can operate on 100% renewable energy,

(b)a clear understanding that our economy can operate in 100% harmony with nature, with zero waste, 100% organic farming and 100% ecological forest management, to protect nature and sequestrate all that surplus carbon, and every business following social and environmental purpose, as well as the financial bottom line;

(c)a clear understanding that we can make a transition from capitalism to a cooperative, regenerative economy in which workers, communities, nature and the planet can all flourish;

(d)a clear understanding that cooperatives, cooperative and community banks and social enterprises are more resilient and suffer less crisis than private neo-liberalized banks and businesses, while also showing far lower wage differentials, and responding to downturns in the economy by sharing work and wages, rather than firing people.

I thank the RSA for being among the leaders in exploring the shape and nature of this new economy.

best wishes,

Guy Dauncey. www.thepracticalutopian,ca

Vancouver Island, Canada