“Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime”. No piece of proverbial wisdom better captures why so many people see education as the surest route out of poverty, and why welfare payments, essential as they are, will never enjoy the same level of public and political support as education spending.

But do we distribute the education budget in a way that is likely to help children overcome the many barriers to learning that poverty places in their way? Is the school funding system designed to give children the greatest possible chance of learning, then earning, their way out of poverty?

The answer, until recently, was a resounding “no”, and for a simple reason: the government spent more money on the education of rich children than poor children, thus ensuring education was more likely to compound than reduce social and economic inequalities. It did so simply because richer children spend more years in education than poorer children, and as children grow, so does the cost of educating them, with each phase of education, from primary school to university, more expensive to deliver than the previous phase.

But a recent report subtitled 'Middle class welfare no more' by Luke Sibieta of the Institute for Fiscal studies (IFS), describes how, as a direct result of policy decisions taken by Labour, Liberal Democrat and Conservative ministers, that is no longer true; how, over a 15 year period spanning four different administrations, the balance of education funding has been shifted, deliberately and decisively, towards the poor.

Building a pro-poor funding system

Three changes instigated by Tony Blair and Gordon Brown began this shift. First, school funding was increasingly skewed towards poorer pupils. Second, the school leaving age was increased from 16 to 18, requiring those who traditionally left after their GCSEs – many of whom come from low income families – to stay in education for an additional two years. And third, despite the introduction of tuition fees, and the oft-repeated claim that this would harm access, the gap between the university participation rates of rich and poor students actually fell over the period (with the highly progressive student loan repayment system ensuring that public subsidies were targeted at graduates with low lifetime earnings).

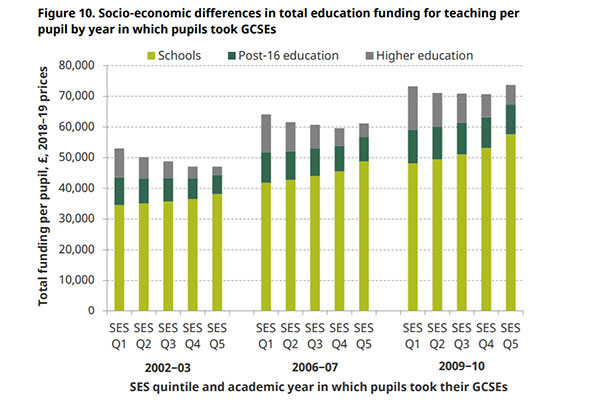

In combination, these changes meant that by the 2010 general election, the government was, for the first time, spending as much on the education of the poorest students as on the richest, as the chart below shows:

Chris Belfield, David Goll and Luke Sibieta, 'Socio-economic differences in total education spending in England: middle-class welfare no more' (c) Institute for Fiscal Studies

What is more, as Sibieta points out:

“since 2010 the funding system has become even more beneficial to lower-income students relative to the better off. This is in part because of further school funding reforms, in part because post-16 participation rates have risen and in part because funding for school sixth forms (where better-off children are more likely to study) has been cut relative to funding for colleges (which are more likely to serve poorer students).”

Alongside this shift from richer to poorer students, another big change has taken place over the last quarter century: an intentional rebalancing of spending away from older, towards younger, students. Spurred by the shocking finding by (then) LSE academic Leon Feinstein in 2003 that ‘bright poor’ children in England can expect to be overtaken by ‘less bright but richer’ children by the age of six, successive governments set about increasing spending on children at the start of their educational journey, where investment yields the highest returns, particularly for the poorest.

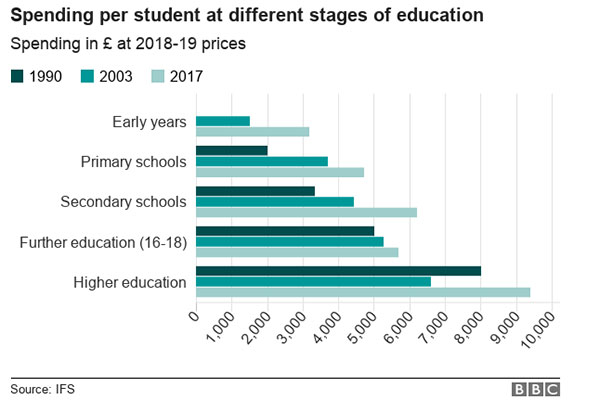

As the chart below shows, between 1990 and 2017, per pupil spending on primary schools increased by 135 per cent, compared with 86 per cent for secondaries and just 10 per cent for post-16. But the fastest growing area of education spending is now pre-school, which has doubled in the last 14 years.

Luke Sibieta, 'School funding: Why it costs £73,000 to educate a child' (c) Institute for Fiscal Studies

To summarise: three big changes have taken place over the past couple of decades. First, poorer pupils now spend longer in the education system. Second, the balance of education spending has shifted away from older students towards the youngest. And third, within each school-aged cohort, funding has shifted from richer to poorer pupils.

Is it working?

A progressive education funding system is only of value if it actually helps the poor of course. But does targeted investment work? The answer, based on England’s recent experience, is a heavily qualified ‘yes’.

In its 2017 report 'Closing the Gap?' , the Education Policy Institute (EPI) reported that:

“the gap is closing, but at a very slow rate. Indeed, despite significant investment and targeted intervention programmes, the gap between disadvantaged 16 year old pupils and their peers [a gap of 19.3 months] has only narrowed by three months of learning between 2007 and 2016….Over the same period (2007 – 2016), the gap by the end of primary school narrowed by 2.8 months and the gap by age 5 narrowed by 1.2 months."

Those familiar with the economics of education won’t be surprised that progress has been so glacial. After all, economists like Eric Hanushek, who have studied the relationship between financial inputs and educational outcomes across multiple jurisdictions over several decades, have shown how complex is the link between the two. ‘Money in’ doesn’t automatically lead to ‘better educated students out'. That’s not to say that money doesn’t matter. Rather that it can matter, depending on how it is spent.

Which brings us to the single biggest innovation in school funding in recent years: the introduction, in 2011, of the Pupil Premium (PP) – an additional £1,320 for primary, and £935 for secondary school pupils who qualify for free school meals. Schools are allowed to spend the PP on whatever they want but are expected to demonstrate that their spending is raising the attainment of eligible pupils and closing the gap between them and non-PP pupils.

A few months ago, Professor Becky Allen from the Institute of Education wrote a brilliant blog trilogy entitled 'The Pupil Premium is not working' which provoked much discussion among educationalists. Parts 1 and 2 set out what Allen sees as the PP’s three main flaws:

First, that it is poorly targeted because poverty is a poor proxy for educational disadvantage (with social factors, like time poverty, often being more important than economic factors), and because PP students do not, in any case, have the same educational needs.

Second, that measuring the size of the attainment gap (whether between or within schools or across the system, whether as a snapshot or over time) is meaningless and misleading. This is partly because the gap is sensitive to all sorts of things that are unrelated to what students have learnt (like changes to assessment and qualifications), but mainly because the size of a school’s attainment gap tells us more about the demographic profile of it pupils than the quality of its provision. In particular, it tells us more about the profile of the non-PP population – that vast group containing 75 per cent of all children whose parents range, as Allen puts it, from “bus drivers to bankers”. Which is why, she argues, demographically heterogeneous schools “that serve truly diverse communities, are always going to struggle on this kind of accountability metric”, whereas a more demographically homogenous school, whose entire population lives on the same large housing estate, will not.

Third, that the goal of reducing the attainment gap drives short-term interventionist behaviour by school leaders and teachers. This behaviour is understandable. If the aim is to increase PP pupils’ performance relative to that of non-PP pupils, it makes little sense to invest in activities that will benefit all the children in the class. Yet, by prioritising targeted interventions designed to benefit PP-eligible children only, schools are deciding, knowingly or unknowingly, not to invest in the one thing we know makes the biggest difference to educational outcomes – high quality whole-class teaching (and, by extension, highly quality teachers).

I agree with Allen’s analysis, but strongly disagree with her conclusion that it might be better “to roll the Pupil Premium into the general schools funding formula with all the other money that disproportionately flows to schools serving disadvantaged communities”.

I disagree in part for political reasons. The Pupil Premium is more than a policy. It is a symbol of our commitment, as a society, to equality of opportunity – to the idea that each of us should be able to advance just as far as our talent and our efforts can take us. That shared commitment has sustained a cross-party consensus on the broad aims of education funding policy at every phase, from nursery to university, for the last 15 years, with social mobility the explicit goal. Discard that symbol and we risk weakening that commitment and undermining that consensus. It would be far easier for a minister who wanted to unwind the progressive reforms of recent years to do so by tweaking an impenetrably complex funding formula than by abolishing a totemic policy like the Pupil Premium.

I also disagree for pragmatic reasons. It is true that the Pupil Premium isn’t perfectly targeted because low parental income isn’t the only factor that impacts negatively on educational achievement. But we should take care not to make the best the enemy of the good. If there was an administratively plausible way for government to target funds on families that are time poor, or where parental qualification levels are low, we could think about ways of adding these to the PP’s eligibility criteria. But there isn’t, so we can’t.

And I disagree because abolishing the Pupil Premium isn’t the logical response even to Allen’s strongest argument – that the PP incentivises sub-optimal spending decisions by school leaders that divert resources away from high quality whole-class teaching. After all, such decisions are not a product of the PP per se, but of the PP’s declared purpose; that of ‘narrowing the gap’. It shows how absurd such a target is that a school where standards are falling, but falling fastest among non-PP pupils would, through a gap narrowing lens, appear more successful than a school where all pupils were progressing at an equally impressive rate. But again, this isn’t an argument for abolishing the PP. It is an argument for government and Ofsted talking less about the need to ‘narrow the gap’ and more about the PP being there to help schools ensure all pupils make good progress.

Recommitting to the fight

So, what should supporters of the Pupil Premium – and the broader effort to reduce the impact of poverty on children’s educational prospects – resolve to do next?

First, let’s not allow the claim that “the Pupil Premium isn’t working” go completely unchallenged. Considering the extent of England’s social and economic inequalities, it could be argued that just preventing educational inequality from worsening is a significant achievement.

Second, let’s continue to make the case for overt redistribution within the education system. That means continuing to shift resources, both within and between cohorts, from students who don’t need additional state support to those who do. This means, for example, making the case for investing more heavily in raising the quality of nursery education and resisting calls to abolish university tuition fees – a regressive proposal which, as Sibieta notes in his report, would, at a stroke, tilt the balance of state education spending back to the rich.

Third, let’s remind people that although money doesn’t automatically lead to improved outcomes, many things that matter to the effort to equalise educational opportunities only come at a cost; the cost, for example, of providing breakfast and homework clubs, individual tuition and booster classes, pastoral support, therapeutic services and all the other things schools do to dismantle the barriers to learning poor children face. Or the cost of trips to the theatre, gallery or museum and all the other things schools do to build cultural capital. Or the cost of careers advice, mentoring, work experience and all the other things schools do to raise their pupils’ aspirations and broaden their horizons.

Fourth, let’s accept that ‘narrowing the gap’ is a largely meaningless target and a counterproductive accountability measure. The aim should be to ensure all pupils make good progress, not for PP pupils to progress faster than non-PP pupils, and government and Ofsted need to say so unambiguously and repeatedly.

Fifth, let’s remember that high quality all-class teaching is the most important driver of student progress. Schools should be actively encouraged to use the PP to support that aim, including by recruiting, retaining and developing great teachers.

Which brings us to the final, and arguably most important, resolution we can make: to think hard, as Allen challenges us to do in her third blog, about why poverty impedes learning and about what that means for the way teachers teach.

Allen’s contention is that the primary reason income inequalities translate into educational inequalities is because of in-class variations in children’s cognitive function – variations which clearly and consistently correlate with socio-economic status.

The most common explanation for these cognitive differences is that poor children are more likely to be exposed to stress in their earliest years as a result of traumatic experiences – family conflict, neglect, addiction, illness, debt and so forth – that are more prevalent in the lowest income households. To protect us, our bodies have a stress management system – a chemical process called allostasis – which can easily become overloaded if called into action too often. And when it is, not only does it damage the body (dangerously raising blood pressure, for example, increasing the risk of heart attack) but it damages the brain, the prefrontal cortex in particular. And because the prefrontal cortex is critical to self-regulation, people who suffer serious allostatic overload in early childhood generally find it harder to sit still, concentrate, follow instructions, plan ahead and remain focused on their goals – all of which have a direct and hugely negative impact on their performance in school.

It is for precisely this reason, Allen argues, that “if we care about closing the attainment gap and we accept the relationship between socio-economic status and cognitive function, then surely our first port of call should be to create classroom environments and instructional programmes that prioritise the needs of those who are most constrained by their cognitive function?”

She then goes on to describe schools (often pioneering US Charter Schools or English Academies and Free Schools) that have done just this by developing models of instruction that are deliberately designed to limit the choice of things students get to pay attention to during class. Armed with a copy of Doug Lemov’s 'Teach like a Champion', teachers in these ‘high poverty, high performance’ schools demand pupils’ total and constant attention, using techniques like SLANT (Sit up, Listen Ask and answer questions, Nod your head, Track the speaker) to ensure minds don’t wander. Like Allen, I’ve been to some of these schools, witnessed their rituals and routines, and experienced the same state of cognitive dissonance she describes: unsettled by the regimentation but blown away by the results. And that’s the key point here. If raising the attainment of poor pupils is the goal, what these schools are doing clearly works.

Which presents a challenge both to those who take a more laissez faire approach to school discipline and classroom management, and to those who advocate positively for child-centred or discovery-based approaches to learning: to set out what gets lost in these ‘high poverty, high performance’ schools’ relentless pursuit of results, and why these other educational or developmental goals are as important as academic attainment to a poor child dreaming of a better life.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Julian,

When people live in poverty – the world as a whole struggles and people see these struggles trickle down into their small communities. It may be true that we have seen great strides in living conditions for most of the world, but there are many people who still fall through the cracks. It is the job of the people to come together as a community and help lift up those who are impoverished. One major factor that research shows contributes to poverty is lack of education. The solution to combat poverty is providing and enforcing better education. Research has determined that there is a direct link between the literacy rate of a country and its poverty rates. We can also look to history and see that counters that invest heavily into an equal opportunity education system they will see amazing results. Research as also looked at the effect of education on people becoming impoverished and noticed that the more educated one is the less likely they are to fall into poverty. One of the biggest factors to this strategy working is making sure education is rid of discrimination of any kind, only then will education work its magic on poverty.Thanks, Julian. It's refreshing to see taken into account the critical role played by childhood trauma in driving low levels of engagement in traditional learning environments. We need a nationwide policy for addressing the consequences of trauma, and measures taken to reduce it in the longer term. Over half the states in the USA now have schemes in place to identify ACEs (adverse childhood experiences) and take early intervention measures, supporting children and parents in making changes. Wales and Scotland have policies in place, but England has yet to address this serious issue, as far as I'm aware.

Julian

Having read the parallel RSA blog by Mark Londesborough on Arts-Rich Schools could it be some of these things that are lost?

*. Inquisitive students: where their education in and through arts and culture fuel their desire for learning about the arts, about themselves and about the world

*. Reflective educators: who are committed to ongoing learning from their practice and from the evidence that can support it

*. Mission-oriented schools: where the arts and culture are integral to the shared purpose of everyone in the school

*. Supportive communities: who engage in arts and cultural activity that helps schools achieve the best for children and who benefit from that engagement.

Or are the SLANT schools culturally rich in their learning?

Julian - thank you for a powerful and authoritative summary.

Two additional points for reflection:

(1) any serious analysis of the long-term effectiveness of the Pupil Premium has been profoundly undermined by (a) its long term uncertainty (not knowing when or if it will continue or terminate, prevents sustained investment in enduring programmes of intervention); and (b) as the real-terms purchasing power of school funding has declined catastrophically, many schools are now using Pupil Premium resources to prop-up mainstream provision ...

(2) there has been a clamour of support, supported by some evidence, for schools adopting the regimes you describe: the analysis, however, tends to correlate the surface behavioural features with the success rather than asking the more profound and essential question: don't pupils always thrive when there are high expectations associated with authentic emotional engagement? It doesn't necessarily require an authoritarian approach ...