Do we still need cash? Do we still need bank branches? It might seem like we can just use contactless and do our banking online. The RSA's latest report, 'Cashing Out', takes these assumptions to task.

Cashing Out finds that a disorderly ‘dash from cash’ would be both economically risky and socially harmful – and we risk sleep walking towards this unnecessary cliff edge.

Here are our top 4 reasons why we need a co-ordinated strategy to make sure we maintain a physical banking infrastructure capable of supporting economic resilience and inclusive growth.

Providing Choice and Competition

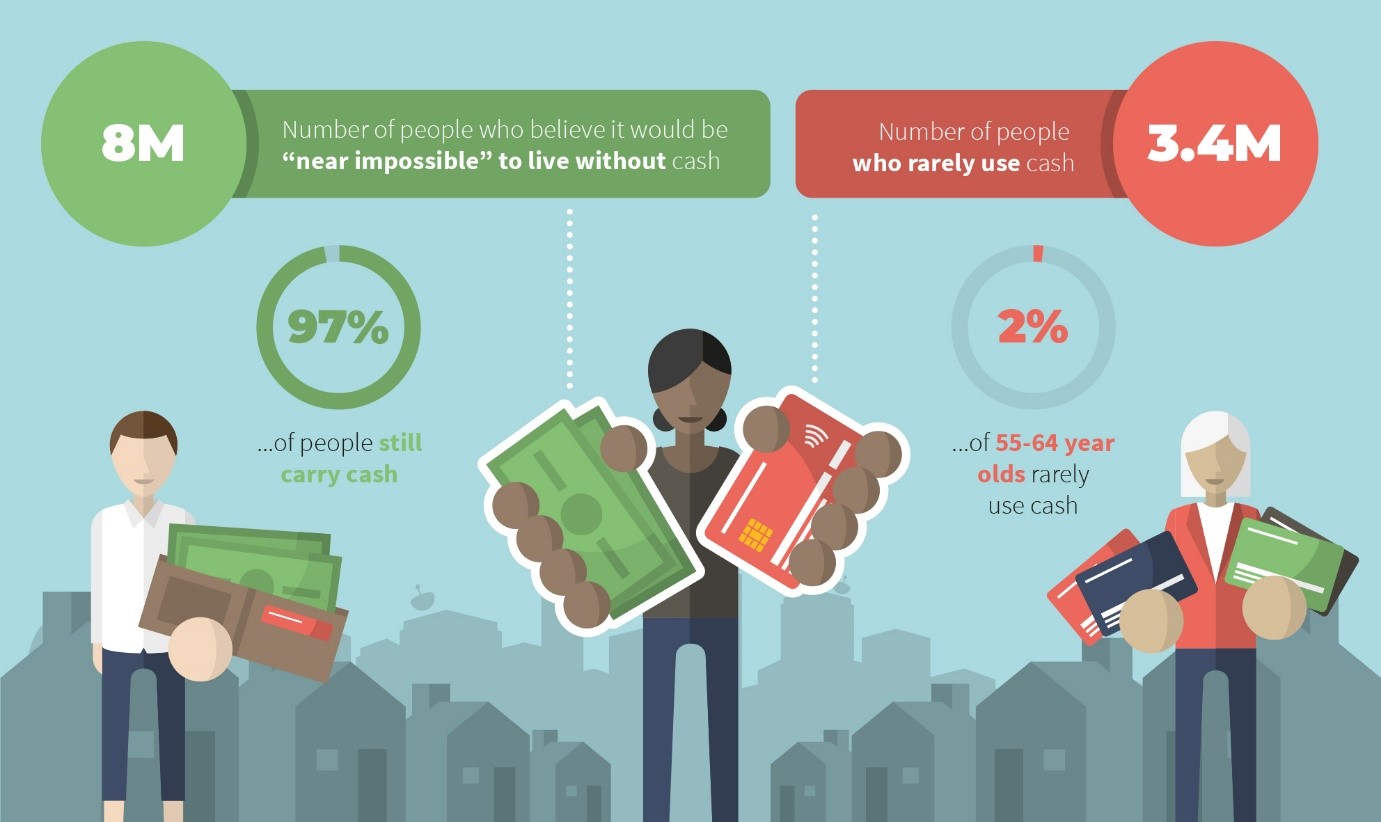

While cash may no longer be king, most of us (97%) still use it in some way or form. Whether it’s for every day essentials or in case of emergency, cash transactions account for a third of all payments - a significant slice of economic activity. The rise in digital payments will continue over the next decade as cash usage continues to fall, but some rely on cash far more than others and those that do are much more likely to come from low income households.

Cash doesn’t discriminate. It’s free to use and everyone has access to it. It provides consumer choice and essential market competition to private digital payment systems. Every digital transaction, whether a contactless payment in your local shop or an online purchase, is making a profit for private companies who are building profiles on our spending habits. Cash allows us direct access to our money without creating data for big advertising agencies to exploit.

But the divide between those who use cash and those who don’t is growing, with 3.4 million having switched to digital and rarely using cash at all, versus 2.2 million people who rely almost wholly on cash. And a much larger proportion of the population are still dependant on cash, with the Access to Cash Review reporting that nearly half of us think that living without cash would be problematic including 8 million, who would find life “near impossible”.

Promoting Financial Inclusion

There are several reasons why some, often more vulnerable groups, are more likely to rely on cash. Despite the rise of banking apps and online tools, many still find cash the simplest and most convenient way to budget and allocate money for everyday expenses. While many of us can easily log on and manage our finances on our morning commute, a staggering number of people have no real alternative to cash with 4.5 million adults not having access to the internet and a further 9.2 million adults having low digital literacy.

While most us take having a bank account for granted, around 1.23 million people live without one, most on low incomes and half of those without a bank accounts earn less than £5,000. Some are wary of using banks due to lack of trust or fear of unexpected fees and charges, and others struggling with debt or lacking sufficient ID are locked out of the system, not even able to access to a basic current account.

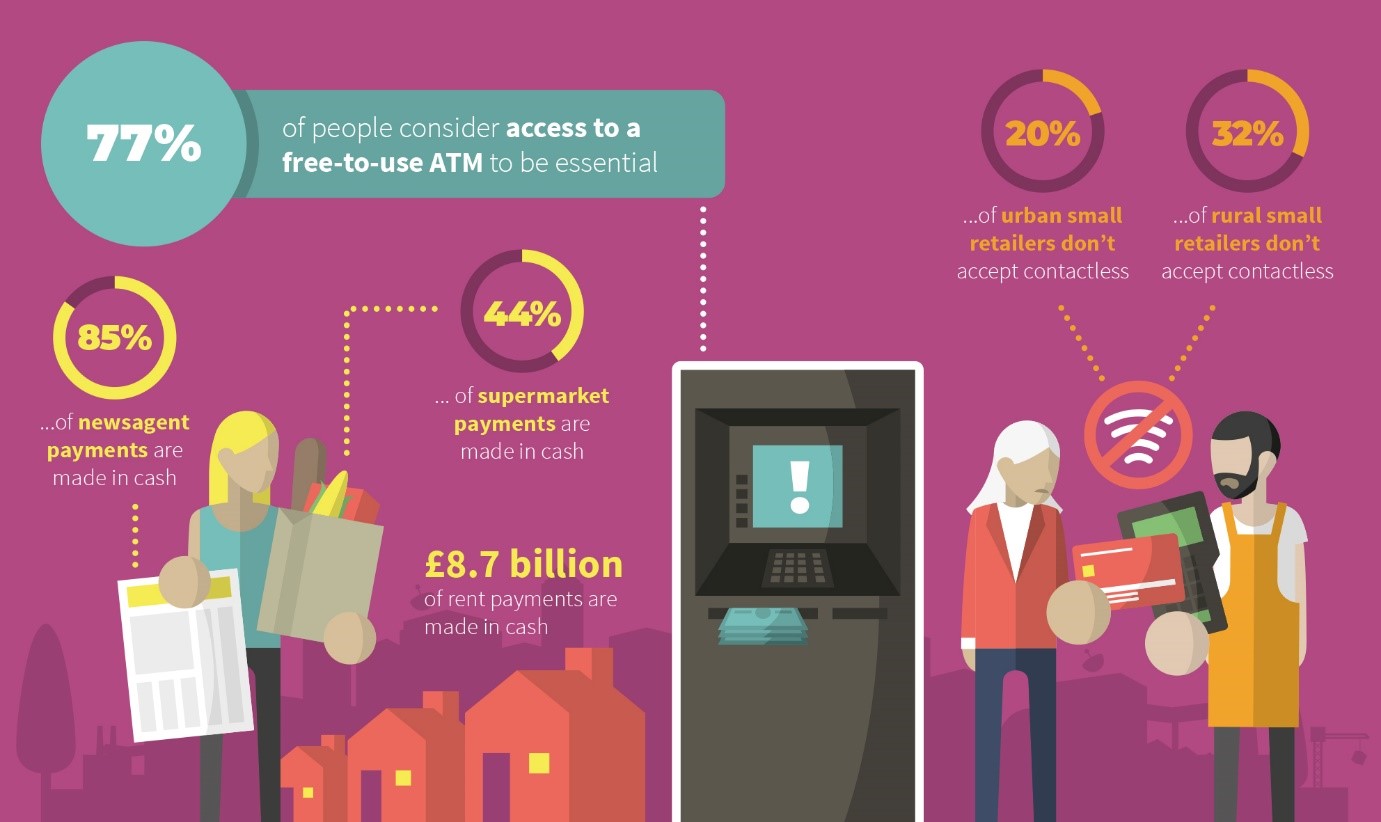

Those who are reliant on cash also rely heavily on the infrastructure that helps it flow through our economy. While there are still a wide range of people using branches including at least one in four from every age group, those on low incomes are more likely to use them regularly. Despite almost everyone using still cash-points and 77% of us considering access to them essential, over 10 million people live more than 1km away from one, with those living in rural areas or on satellite housing estates and on low incomes most likely to find it harder to access them, as well as those with additional needs or mobility issues.

Supporting Local Economies and SMEs

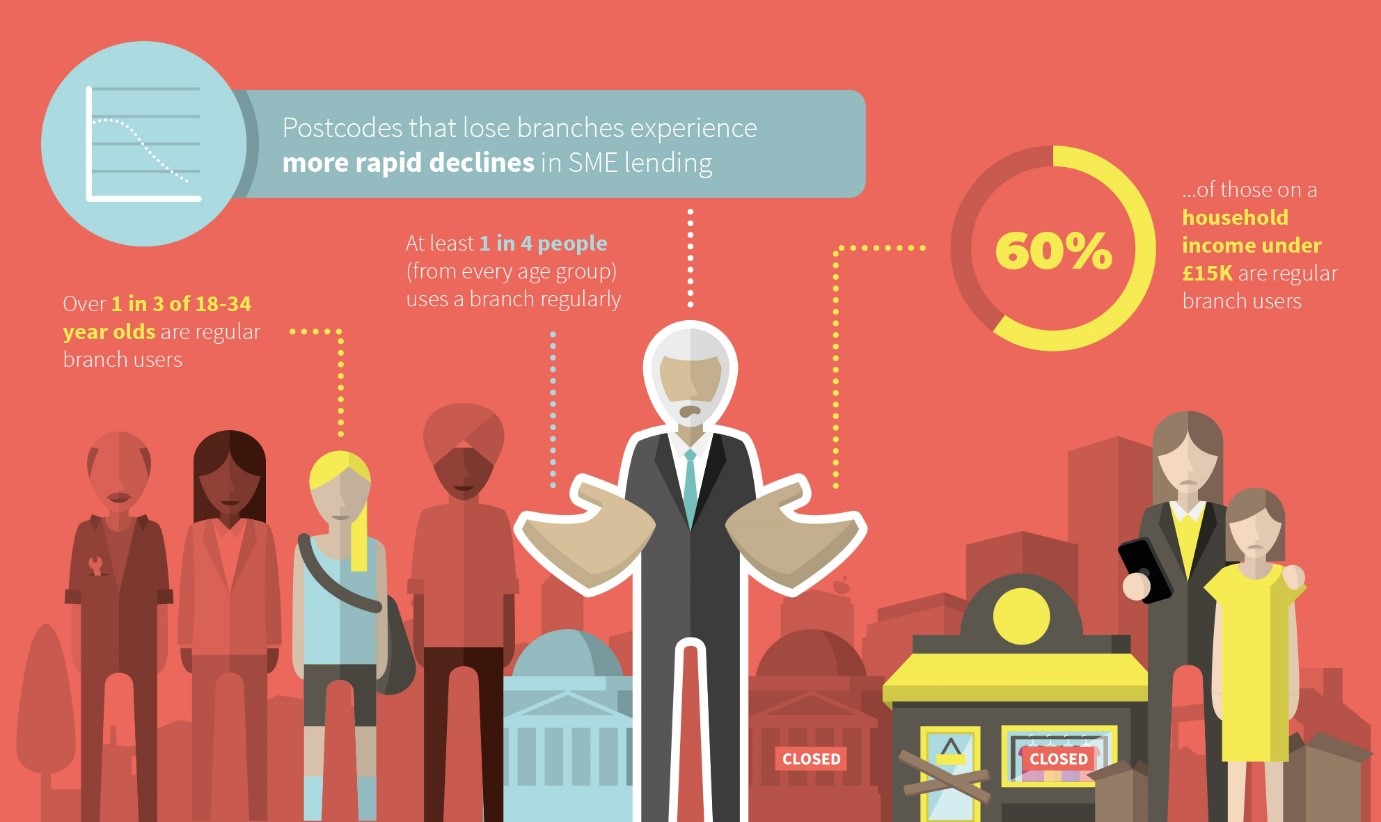

The number of UK bank branches is declining rapidly. Between 1989 and 2012 Britain lost 57% of its bank branches, falling from 20,583 to only 8,837.

The latest wave of branch closures announced recently by Santander (which is also putting 1,270 jobs at risk) along with latest data on branch closures from consumer group Which?, shows this trend is set to continue.

As well as the impact on individuals, branch closures can also shake the foundations of small businesses, particularly those such as newsagents who take 85% of payments in cash, if their communities are left without essential facilities they need to handle and process cash effectively.

Our research also shows that these swathes of branch closures are also having a negative impact on small businesses’ ability to access finance. Analysis on available bank lending data shows that areas experiencing branch closures also experience a greater fall in lending to SMEs (Small and Medium Enterprises) than areas without a closure.

Much more needs to be done to assess the economic impact of branch closures and local authorities need to do more to ensure essential cash infrastructure remains available, particularly for small businesses.

Boosting Economic Resilience

Cash is free to use, accessible to all and leaves no digital trace. Digital payments systems on the other hand bring with them two major risks that cash does not have to carry, IT failure and cybercrime.

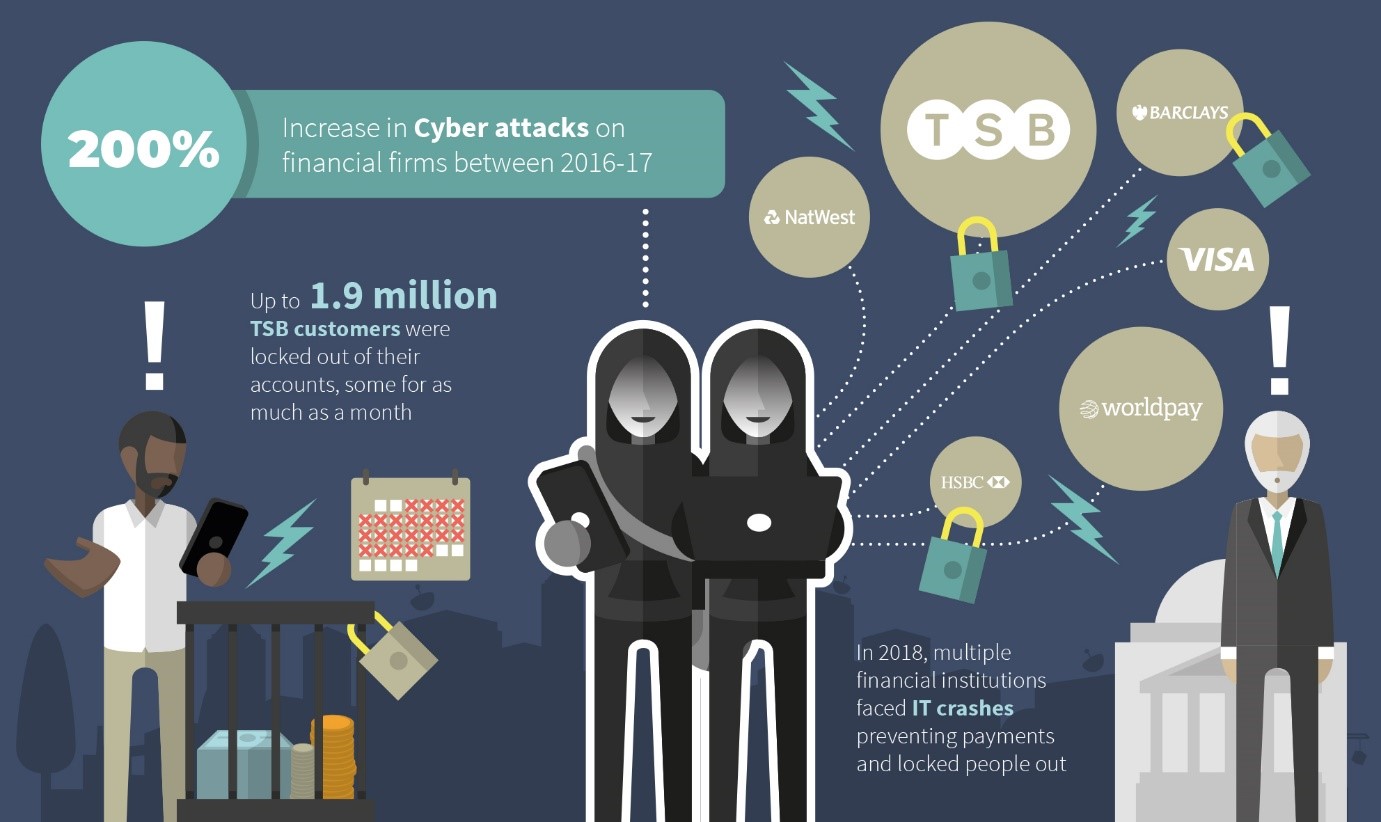

IT failures, which can often provide minor inconvenience to mobile banking app users, can and do cause major global disruption. Throughout 2018 we saw the collapse of the Visa network, major disruption to all the big banking groups, and a major IT meltdown at TSB with nearly 2 million customers experiencing major issues and some unable to access their accounts online for over a month.

Between 2016-17 cyber-attacks on financial firms went up 200%, showing that digital payments are very much a target of hackers and fraudsters looking to disrupt the system. Protecting digital payments from cybercrime is now one of the top priorities of the Financial Conduct Authority after fining Tesco Bank £16.4 million for deficiencies in its cybersecurity systems.

While cash can also be used for fraud and criminality, this is quite minor in comparison with roughly £4.83 million counterfeit notes in circulation compared to the £3.1 billion cost of cybercrime to UK consumers.

When digital payments come up against these threats, cash carries on unphased, providing stability and security as a backup everyone can turn to.

The rise of digital banking has revolutionised how many of us manage our finances and make our purchases. However, we are far from a position where everyone can thrive without cash.

These four reasons to protect cash and branches highlight the hidden costs and consequences of moving to a cashless society. We must maintain access to a free at the point of use payment and cannot afford to phase out cash until we have an inclusive and accessible alternative that works for everyone.

Find out more by reading the full report Cashing Out: the hidden costs and consequences of moving to a cashless society or by reading the Executive Summary of the report online on Medium.

Mark Hall is Deputy Head of Engagement at the RSA. He leads our work supporting an emerging network of regional co-operative banks, which was set up as a practical response to the issues identified in this and previous RSA research on the role of banking in supporting inclusive growth. You can find him on twitter @MarkHallRSA or get in touch via email at Mark.Hall@rsa.org.uk.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

First, cash is far from free. It needs to be designed and printed/minted; it needs to be transported around in armoured vehicles; you need to go and get it from an ATM; you need to carry it around with you, and perhaps store some of it at home; when you spend it, it needs to be counted, and then transported elsewhere; some of it gets lost/stolen.

Second, for the above reasons, cash is a lousy way to ensure social inclusion. In fact, forcing people to rely on cash rather than ensuring they can benefit from digital inclusion seems to be discriminatory itself.

While physical impairment might prevent some people from using digital payments, it may also prevent them from using cash, but that doesn't mean we should live in a barter economy. This report would have been far more useful had it looked at WHY people still need to use cash and what can be done to eliminate that burden.

These points are all very well made and the concerns raised are parallel to those under discussion at the BoE in their 'Future of Money' forum.

Unless a form of 'currency' with the same attributes as cash can be realised these things will come to pass if people do not still have access to it; but how is a supply and access to that supply to be maintained if hardly anyone is actually using it.

It seems to me that the first worry is that of having day to day transactions totally dependent on generated power, as you say. There would always need to be a disaster recovery plan and currently cash is the best idea available. It is really hard to envisage an alternative which is not electronically based, other than what we already have.

I wholeheartedly agree that the move to digital money is a threat and a divide, both for lower-income and older people. And a difficult one to address given that large organisations, banks and corporations seem to control what services are provided.

I see it as part of a bigger problem, which is the loss of 'human-ness' in our day to day interactions with organisations: the automated telephone responses when contacting services; the 'process-oriented' approach to customer service; dealing with organisations that no longer provide a telephone number, merely a 'chat-option', where half the communication is automated and out of context to the communication required by the customer. These are some examples.

In my most recent dealings I have come across situations where the customer service operator is trying to give me clues about how I answer a particular question, so that they can get through to the next part of the customer-facing process, controlled by a computer. They know that the processes aren't working with real-life but are limited by the restrictive processes that the IT developers and business analysts have implemented.

When I trained in IT at UCL in the 80s we had a lecture on ethics, warning us that with the deployment of technology we had a moral obligations. It seemed over the top to me at the time. Now I see how the growth in customer-facing technology is making people feel out of control, both the customers and the operators who are trying to use the systems to do their job. Feeling out-of-control is a key determinant in mental well-being. How organisations are relying on technology to improve efficiency may well turn out to be a double-edged sword, cutting costs but creating health and well-being problems for people working with the technology solutions.