In order to transform public services and improve population health outcomes, we need to accelerate the social innovation process in communities - co-creating solutions from the ‘bottom up’ to tackle complex societal challenges. There are wider economic and societal benefits to be realised from embracing the efforts of community organisers and social entrepreneurs. The challenge is how exactly to do this given that the system and incentive structures tend to crowd out innovation. This was the theme explored by a cross-sector group of people passionate about supporting social innovation in the north west recently.

The social enterprise sector is growing rapidly. There are tens of thousands of social entrepreneurs in the UK whose fledgling social businesses have been incubated and supported with the help of game changing organisations like the School for Social Entrepreneurs, UnLtd and through initiatives such as the RSA’s community business leaders programme. Today one in four people who want to start a business want to create a social enterprise, evidence perhaps that a social movement is underway, in which citizens are seeking to claim back their community, their local economy, and carve out new ways of responding to the seemingly intractable social problems that public sector organisations have historically struggled to address.

There are incredible examples of social enterprises and community led initiatives in which ordinary people have took it upon themselves to do extraordinary things, and in doing so have become extraordinary people. For example, Jane Davis who founded The Reader Organisation which pioneered the use of shared reading to improve wellbeing and reduce social isolation or the community housing cooperative led by the citizens of Granby Four Streets in Liverpool which has undoubtedly generated wider health and wellbeing benefits for residents. Social entrepreneurs and community organisers often reach parts of the community that the public sector can’t. In particular, they can unlock the assets of people and communities, provide a means of accessing different forms of capital and create ‘fail safe’ spaces to try and test out new ideas, as follows.

Social innovation processes are typically powered by citizens, who sweat the community assets and resources at their disposal and call on the goodwill of local people - demonstrating the value of other forms of capital; particularly the social capital that strengthens communities. For a number of reasons, social entrepreneurs and community organisers are critical agents in this process. They often live in the communities they operate, they have a deep understanding of local problems, and they bring their creativity, community connections and local knowledge to bear to address such problems working with the community as an asset. They bring a unique set of skills and competencies to the table. They can help us to ‘see’ new ways of understanding and responding to societal problems which could inform the strategic planning of public sector organisations.

Social entrepreneurs and community organisers can open doors to new forms of capital, whether that is through trading activities, grants, social investment or the goodwill and generosity of citizens themselves. Social entrepreneurs for example, employ business approaches to tackle social problems, and consequently they have one eye on the sustainability of their social endeavours through ethical / social trading. This is a big advantage for policy makers and public sector leaders when one recognises that serious conversations need to be had about who will finance the prevention aspects of the population health agenda moving forward, which is desperately needed to ameliorate pressures on overstretched public services.

However, in order to unlock social investments social entrepreneurs need to demonstrate pipeline sales/contract opportunities, and so they need the backing and support of public sector organisations to realise these opportunities. This requires changes in the way that the public sector commissions services. Without stronger partnerships between voluntary, community and social enterprises and the public sector through commissioned, contracted work, this much needed investment will remain inaccessible which arguably the public sector can’t afford to miss out on. This is one of the important reasons why implementing the Social Value Act intelligently can reap multiple benefits for communities and public sector organisations.

Finally, social entrepreneurs and community organisers provide safe spaces to test out new ideas and approaches. The public sector’s appetite for ‘risk’ is somewhat limited, which one can argue is understandable in having to account for public expenditure and often working with some of the most vulnerable in society. Yet without the creation of ‘fail safe’ spaces, we cannot discover new ideas and possibilities that will ultimately inform the evidence base of the future. Social entrepreneurs and community organisers operate in the space between the state and the private sector, which is more amenable to trying and testing out new ideas, often through processes of co-creation and co-production, ensuring that citizens are actively involved throughout the entire innovation process. This has the added benefit of ensuring new innovations respond to social needs as identified and described by potential beneficiaries, and it also creates a sense of ownership and buy-in for new products, services and processes.

The challenge, discussed by a group of advocates last week, is how to leverage these benefits. Despite the advantages that social entrepreneurs and community organisers bring in terms of accelerating social innovation processes, the engagement with, support for and commissioning of such activity is varied at best. We see that engaging communities is uncomfortable for many charged with designing and providing services; commissioners like the known rather than the start-up which they perceive as being the biggest (financial) risk; and that social value still isn’t routinely understood as part of a commissioning process.

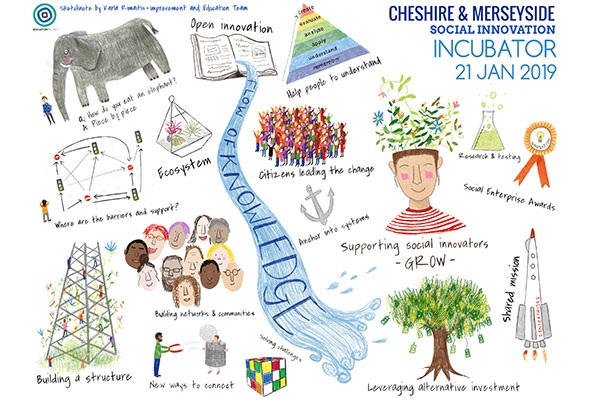

We would be far more effective in our efforts to bring about better outcomes for our communities if we adopted more of a pincer type approach; with top down strategic approaches and bottom up grassroots efforts combined in a coordinated way to unleash the energy for change in public organisations and communities. In the language of ‘cultural theory’, we need to strengthen the relational, community-led response to societal challenges and not simply rely on hierarchical, institutional power to attempt to solve things. We must use the power of the institutions where it offers advantage; the NHS 10 Year Plan and the development of the Cheshire and Merseyside Care Partnership strategic plan underpinning it represent an opportunity to embed social innovation processes at its heart. The visual notes of the conversation illustrate some of the ways we might approach this task.

Stronger collaborations between community organisers, social entrepreneurs and public sector professionals will provide an interface for imagining and discovering new ways of responding to complex societal problems. This is the space the RSA are working in with the ‘public entrepreneur’ programme and that the work to develop a Social Innovation Incubator in Cheshire and Merseyside seeks to occupy in the health and social care sector. How can those working creatively within the system actively grow an ecosystem of social innovation and enterprise that empowers citizens to make the changes they want to see in their community?

To do this the public sector must open its arms to the efforts of social entrepreneurs and community organisers and embrace what they bring to the table to accelerate social innovation processes in communities. This will not be easy of course, as it will require public sector leaders to give power and legitimacy to citizens to lead the change that’s necessary. The establishment of a vibrant social innovation sector that puts local citizens and social entrepreneurs in the driving seat of a long-term plan for the Cheshire and Merseyside region will also require the co-ordinated provision of support needed to accelerate social innovation processes. As Dave Sweeney, implementation lead for the Cheshire and Merseyside care partnership noted, “we need different ways of working to engage our communities in meeting our health and care needs”. Those pioneering, courageous public sector leaders who are currently attempting to do this will be rewarded richly for having activated their community to be the change that they want to see in the world. The energy for change this will unleash will be the driving force for better health outcomes, societal change and a more equitable world.

Ian Burbidge is an Associate Director in the RSA’s Public Services and Communities Team @ianburbidge

Mark Swift is an RSA Fellow, a social entrepreneur and Founder & Chief Executive of Wellbeing Enterprises CIC, and is doing an ESRC funded PhD in Social Entrepreneurship at The University of Liverpool @mark_sw1ft

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Great article and most interested to learn how this work is tying into the Next Stage Health Care and Public services event that Mark Hall RSA is promoting (19 March)? Especially keen to see the advancement of Community Circles.

Thanks