With the number of people sleeping rough showing signs of decline after an extended period of rises, it’s tempting to feel optimistic. However, we shouldn’t get complacent as the headline friendly figures on homelessness are more complex than they first may seem.

Each year councils in England report on the number of people sleeping rough in their area on a single winter night. The figures have shown an alarming rise of street homelessness in recent years, with rough sleeping increasing by 165% since the tables began in 2010. For most this trajectory is unsurprising as the homelessness crisis plays out in the public eye.

The most recent figures, however, buck this trend and instead suggest a national decrease of 2% in the number of rough sleepers from 2017 to 2018. The Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government James Brokenshire was quick to celebrate the work of the Conservative government in reducing rough sleeping. In response to the new figures, he said he was "pleased to see [the government] strategy to end rough sleeping, backed by a record investment of £100m, is starting to have an effect". Whilst he is thankfully under no illusion that the problem is not solved, his commentary suffers from not digging deep enough into the data.

How do we count the number of people sleeping rough?

The rough sleeper count has always been a controversial dataset. Whilst there is a clear need for an attempt to quantify the scale of rough sleeping at a local level, many argue the means of achieving this is not fit for purpose. Crucial to an understanding of this data is the detail that councils have a choice in how they reach their figure. They can either:

- conduct a count of people sleeping rough on a single night

- use a second party count to make an estimate

- use local intelligence to reach an estimate without going out to count at all

In the case of those taking part in a count, criticism is focused on the likelihood of underestimating the number of people in need. Many rough sleepers, particularly women, will be hidden from view to protect their safety and so may not be counted. Further, the count can be highly dependent on the day it is conducted. For example, if on the count night there are Severe Weather Emergency Protocols in place, more hostel spaces will be available than usual and so the count will not represent the norm.

Councils can also change the approach they take and each year some move from an estimate to a count and vice versa. With any research, we need to be wary of when these sorts of changes happen and, if we can ascertain it, the impact they have on the data. For this data we have historical publications dating back to 2010, which can help us to understand what the implications might be.

Have the change in rough sleeping figures been caused by a change in methodology?

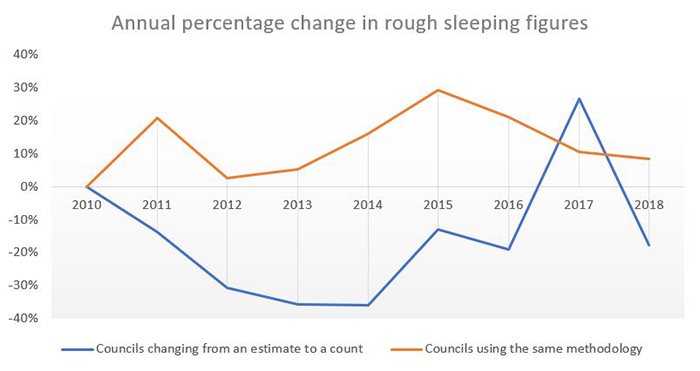

When we isolate just the councils that have changed how they reach their figure by moving from an estimate to a count, we see that this move consistently leads to a decrease in the number of reported rough sleepers. Data from 2016 to 2017 appears to go against this trend, but this is driven by just one (large) anomalous council. This pattern is perhaps intuitive. Local intelligence may suggest a certain number of people sleeping rough but locating them on one specific evening is a much harder task.

By contrast, when the method stays the same the reported number of rough sleepers increases. Again, this is makes sense. A consistent methodology paints a more accurate picture of trends as the data is comparable to the year before.

When looking at the data for 2018 through this lens, the same pattern holds. The reported figures are down 18% in councils that have changed methodology from an estimate to a count, and up 8% when councils have stuck to the same approach. What sets this year apart is the number of councils making this change. In total, a quarter of councils made the move from an estimate to a count (or a second party count). This is the biggest shift to date and has led, on balance, to a decrease of 2% in England. Put simply, so many councils have changed to count the number of rough sleepers this year that the decrease in this group has overshadowed the upwards trend elsewhere.

For example, in Westminster, where a count is always carried out, a record 306 number of people are reported to have slept rough on the count night. This is up from 217 last year. By contrast the biggest decrease was seen in Brighton and Hove, where the council moved from an estimate to a count and reported a fall from 178 to 64 rough sleepers.

Contrary to Brokenshire’s comments, this interpretation of the data suggests that the Rough Sleeping Initiative is not enough to tackle extreme forms of homelessness. So far, the government has brushed aside suggestions that welfare reform, including the move Universal Credit, are related to the rising homelessness. Given another year of increases in rough sleeping, it’s time this relationship was addressed.

The importance of honesty

There is also a wider conversation to be had on how we use data at a time when statistics are saturating the news cycle.

With trust in institutions and experts waning, we need to ensure that when data is put into the public domain it paints an accurate picture. Honest and transparent narratives are essential.

When it comes to homelessness, if the headline that rough sleeping is in decline doesn’t sit well, it’s because there is more to the story. Over simplified interpretations might make for snappy headlines but obscuring changes behind the scenes will ultimately only lead to greater scepticism.

Related articles

-

The social housing green paper shows Whitehall’s wilful ignorance of social housing

Atif Shafique

The social housing green paper does little to confront the challenges facing the sector.

-

The hidden poverty in our schools

Laura Partridge

This article explores the plight of the thousands of children living in destitution in the UK who do not appear in school poverty statistics because their families, owing to their immigration status, cannot access public funds such as housing benefit and child support. Local authorities, schools and third sector organisations are picking up the pieces left behind by national immigration policies.

-

The Cohousing 'Fix'

Author Block

Could intergenerational cohousing, clusters of homes with shared resources, provide innovative solutions to pressing housing challenges? Supported by the RSA, Nottingham Civic Exchange and THiNK in NG, Nottingham Cohousing brought together a roomful of people including community workers, architects, developers, finance experts, FRSA and potential cohousing residents to see if it might.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.