New data collected from local authorities shows spike in pupils being admitted to schools for excluded pupils in the first term of Year 11, ahead of the January school census that determines if their results will count towards the school’s total.

As part of the RSA’s Pinball Kids project, examining the root causes of rising school exclusions, we requested data from over 300 local authorities under the Freedom of Information Act to understand the link between the pressure on schools to achieve excellent exam results and school exclusions.

The performance of schools are judged by the exam results of their pupils. For GCSE exams in Year 11, the census of which pupils are in which school takes place in January. If a student is at a school for this census in January their exam results will count towards that school’s performance, even if they move schools before the exams.

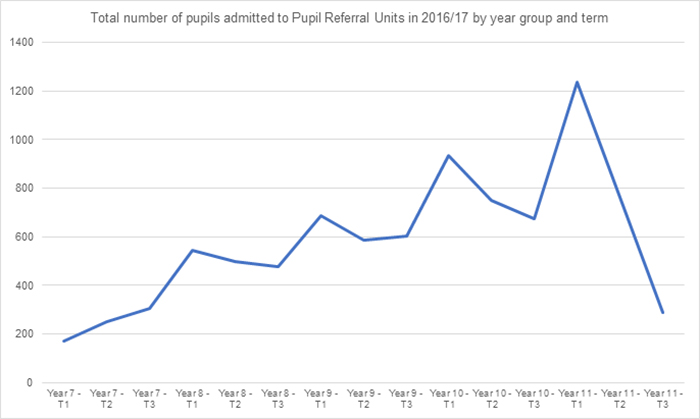

We were interested to see if there is evidence for the claim that schools are using exclusions to improve their results. Our research found evidence to support this argument: a spike in admissions to Pupil Referral Units in the autumn term of Year 11, the final term before the census deadline.

The rise in student exclusions

On average, 41 pupils are permanently excluded from English state schools every day. The rise in school exclusions has dominated the education headlines over the past year. Government data shows a 15% increase — from 6,685 to 7,720 between 2015/16 and 2016/17 — in the number of young people expelled from their school with no hope of return.

Students eligible for free school meals, those with special educational needs and disabilities and those from certain ethnic minority groups are significantly more likely to be excluded than their peers.

The rise in school exclusions results from a mix of factors. These include funding and resource constraints faced by schools and agencies that support vulnerable children, perverse incentives caused by the accountability regime, and curriculum reform making learning less accessible for some pupils.

Excluding Students from School

Together, these factors create the perfect storm for the country’s most vulnerable children. They leave headteachers facing a headwind of difficult decisions, having to carefully weigh competing rights and interests.

This includes the disruptive student who may require additional support, the rest of the class that deserves to learn, and the teacher who needs to be able to pass on their passion and knowledge free from excessive hindrance or threats to their safety.

Teachers and heads face pressure from parents, each of whom wants the very best for their child. Inevitably, when it comes to managing classroom disruption, the outcomes some parents seek in pursuing the best for their child will be at odds with those of others, although their goal is the same.

Once a school has excluded a student, local authorities have a legal duty to place the child back in full-time education within six days.

Many local authorities operate Pupil Referral Units, specifically designed to accommodate such pupils. We asked these local authorities to provide the number of new students who entered these specialist schools in each school term.

78 local authorities with Pupil Referral Units responded in full (the only anomaly being a few instances where local authorities recorded a value of ‘less than 5’ for some terms, which we counted as 2 to allow easy comparison.)

What the data from our research shows

Taken together, the data from local authorities demonstrates that, while there are consistently more pupils admitted in the first term of any school year, there is a significant increase in Pupil Referral Unit admissions in the first term of Year 11. Admissions in that term account for nearly 15% of total admissions reported to the RSA by responding local authorities.

There is a sharp drop-off in admissions in the second and third terms of Year 11, when the rate drops to levels recorded only for Year 7 pupils.

It is important to recognise that some pupils captured in this data will be attending a Pupil Referral Unit part-time, as part of an arrangement with their mainstream school that seeks to ensure they get the support they need in order to avoid a permanent exclusion. In these cases, it is likely that they appear on the registers of both their original school and a Pupil Referral Unit. However, recent analysis from ISOS Partnership suggests that three quarters of pupils in alternative provision are there full-time.

The findings of this RSA project, supported by the Betty Messenger Charitable Foundation, come ahead of the government-led Timpson review into school exclusions, which is expected to be published in the coming months.

Why are schools excluding students to improve exam results?

Interviews with headteachers for the Pinball Kids project have revealed the immense pressure that headteachers experience to achieve good progress and attainment scores.

The number of school leaders who enter the profession to game the system at the expense of the children they teach is vanishingly small. However, under the current system a poor set of exam results may sound the death knell for a headteacher’s career.

Even if it doesn’t, the almost inevitable attrition of pupils to other “better” local schools and loss of associated funding can have devastating effects. Excluding pupils likely to underperform - and distract others from learning in the process - may seem like the lesser of two evils.

More action from government needed to build shared responsibility for school exclusions

We welcome the Department for Education’s recent commitment to refining the calculation of Progress 8 scores to ensure that a small number of very negative scores do not have a disproportionate effect on a school’s overall progress score. However, we would welcome further steps to reduce the pressure of accountability including considering schools’ average performance over multiple years and responding to poor results with support, rather than punitive measures.

Further to this, we are interested in exploring how shared responsibility can be created across local education systems, building on successful approaches taken by some local authorities, and understanding how the very deliberate efforts of some schools to be inclusive can be better recognised and rewarded.

As I explored in my recent RSA journal article, we recognise that beyond the headline figures on formal exclusions, there are many ways in which young people are informally excluded from education.

In our research to date, we have seen exciting work from some schools that are firmly rooted in building fantastic relationships both within the school, between the school and families, and with public services, charities and the wider community. These are themes that the RSA Pinball Kids project will continue to explore.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

I would not be surprised at a link between exclusions and grading of school performance. It has been known even for PRU to exclude children over a schools inspection period. The issue is trying to get to the ground floor of the problem. Any exclusion occurs because the school is having too much difficulty with the pupil, be that actual inability to perform well to lift the schools numbers, or behaviour that cannot be corrected and that will lower the schools grading.

Many thoughts about this.

Maybe a start /finish point system where children have issues. So looking at overall improvement of a child with issues while in the school, rather than a one for all end goal.

Its a bit tough for teachers and school re bad behaviour effecting school image and grade, again some kind of indicator grade to the child's underlying difficulty and level of bad behaviour, inspectors really ought to be totally aware of the range of problems.

Maybe schools would be more inclusive if there was a recognition of the hard work they put in with poorly achieving children and were awarded points for this.

Education is more than training kids to perform for exams. It s about encouraging free and creative thinking to solve problems , not just repeating words they have learnt.

The children in our society should be the focus, the schools educating and enabling happy, secure considerate and achieving pupils ready for the adult world.

But that's a dream, kids are often very difficult, whether it was the spell of videoing people they were pushing off bikes and circulating them or the spate of suicides or the current knife craze.

The report on exclusions is the tip of a social iceberg.

Thanks for your response, Yvonne. Completely agree that we need to find a way to better recognise inclusive practice. We'll certainly be looking at this in our research.

This update reflects the Education Committee report last July on exclusions - https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmeduc/342/34202.htm

There's no doubt that some schools are gaming the system but I sense these are in the minority and are being weeded out. It's interesting that the new Ofsted Inspection Framework now specifies "off-rolling" as part of the proposed Leadership and Management review. It's clearly a concern.

Thank you for responding Sean. The education select committee report definitely picks up on similar ideas. And we will be following with interest developments re: Ofsted and off-rolling.

Fantastic to see this being called out and we're hearing more murmurs of schools implementing a 'no exclusion' approach (which on a statutory level is controversial) and it requires a certain dedication and intelligent engagement with students most schools are not flexible enough to provide. Or some could argue choose not to try, because they see it as totally impossible to sustain alongside running the wider school-- like providing a different vocational curriculum option, employer engagement, etc. It's intensive. More importantly, often, it's not nearly anything as malicious as exam grades or performance, just budget cuts leading to lack of pastoral care and support creating then a systemic issue of the students' situations becoming totally nonviable for the school because they are disengaged in the standard educational process; they can't cater to individual's needs. Not entirely dissimilar to the travesty in SEN more widely. Absolutely, the government should re-think how schools are incentivised, but also clearly the structural issues (from funding, as well as Ofsted expectations, etc) that lead them to feel they can no longer support a child. Poorly explained perhaps on my part, but interested in others' experience of how this manifests.

NB On a different level, as a Governor, in my experience there is another gap here: Governors have to ratify exclusions, yet many of us are removed and would struggle to assess the full scope of one student's situation -- and possibly if we have no direct experience with exclusion so it seems a simple operational decision but if you have been to a PRU and met young people excluded you know its so much more. And there are no direct checks (to memory) that would ensure a child's academic performance is taken out of the equation to focus on the reasons for the decision not the 'symptoms'. It's a horrible decision to have to make for the Head teacher, but also the Governing board isn't always equipped to push back or be as helpful as they could when this occurs or offer the right support.

Just a thought about the other factors and awareness that needs to be raised.

Thanks for your reply, Ashley. It's interesting that you raise governor involvement in exclusions. We're planning to do some research with governors and it would be great to involve you if you'd be interested.

Dear Laura,

Many thanks for your article, which makes for an interesting read.

However, I am a bit sceptical about the differentiation made between correlation and causation. In my experience and to my knowledge, permanent exclusion in English schools is always a last resort, and always a very lengthy process in which a number of stakeholders are involved.

In my opinion, and purely based on my observations, indicators like poverty, neglect, violent households, drug addiction, broken families etc. have a huge impact on behaviour. The lack of sufficient provisions to provide a safety net for pupils affected allows the problem to become unmanageable. I would very much welcome a deeper analysis of the aforementioned factors which, I believe, would illustrate a clearer picture of correlation and causation with regards to school exclusion.

If I may go slightly beyond the topic, in recent news it was suggested that the rise in knife crime was caused by cuts in the Police force. The Police however does not work at the root of the problem (causation), it merely may or may not serve as a deterrent to carry out a crime. The suggestion that school exclusion contributes to knife crime is equally flawed: young people with a low threshold for violence are more likely to be excluded, and are also more likely to commit violent crimes (correlation, not causation).

In addition, I believe that in your analysis, not enough attention is being paid to the needs and rights of pupils who do not engage in antisocial behaviour. I feel that this carries the risk to portray excluded pupils as simple victims of a system purely focused on exam results, whereas schools take their duty to care for all pupils very seriously.

Thanks for your comment, Danny. I agree with you about the importance of underlying causes/systemic factors. This is something I have written about elsewhere (https://www.thersa.org/discover/publications-and-articles/rsa-blogs/2018/09/a-perfect-storm-how-forces-conspire-to-let-down-the-nations-most-vulnerable-children) and which we continue to explore.

And I'm not sure if you'll have seen the latest RSA journal in which we have written about the difficult job facing school leaders and staff around balancing the competing rights and interests of the many children they serve: https://medium.com/rsa-journal/pinball-kids-fae8e62d894c. Happy to post a copy to you if you haven't had one yet!