Today we have released our new report ‘The Road the Resilience’, which tells the story of building a network of community stakeholder banks across the UK.

This isn’t just an interesting or inspiring story. It’s crucial to reducing regional inequality across Britain.

Because we lack truly local banks, Britain doesn’t support local business as much as other countries like Germany or the United States. We have seen that local community banks can make a difference. It’s time to expand them across the country.

“A local bank [is] an important civic institution. Banks do not just cash checks and make loans - they also place ads in small town newspapers, donate to local non-profits, and sponsor local Little League [baseball] teams. As towns lose banks and bankers, they also lose important local leaders”

Randal Quarles, Vice Chair for Supervision, US Federal Reserve.

See our 12 recommendations for building banks to level-up Britain and read the report

Banks and regional inequality

Britain today has some of the highest levels of regional inequality in Europe. By some measures, the gap between parts of Britain today is as wide as the gap between East and West Germany when the Berlin Wall came down.

Long-term government underinvestment in our regions is a big part of that picture. But another key factor is how local banking sectors work – or don’t. Put simply, our banking industry is not working anything like as well as it should.

Following the 2008 financial crisis, British banks received a £500 billion bailout, alongside new regulatory arrangements. This should have led to more credit being available to local small and medium businesses. In fact, the credit supply shrank.

In 2016, a survey from the Bank of England reported that 30 percent of small businesses were unable to access the necessary finance they need to grow. These are not bad businesses. They are viable businesses currently being underserved by the banking industry.

At the same time bank branches are closing, hurting local communities.

The UK has lost almost two thirds of its bank branches in the last 30 years. In the past decade, the rate of closures has intensified, hitting rural and more deprived communities the hardest. 13 percent of all free-to-use ATMs in the UK closed in the past year.

Meanwhile, over one million adults in the UK still lack a full bank account. Around 3.2 million people are in severe problem debt. This creates barriers to participation in the economy, and these barriers have been exacerbated during Covid-19.

We need to change this picture of regional inequality. And the only way to do that is to disrupt the practices of banks.

The shape of the banking industry is skewing the shape of society

Part of the reason for these problems is that the UK banking sector is dominated by a few monolithic banks. 75 percent hold their main bank account with one of the major four banks.

Large national or international banks have relatively little knowledge of local businesses or local area’s needs. They rely on old fashioned legacy systems (e.g. telephone banking) and find it difficult to provide tailored support.

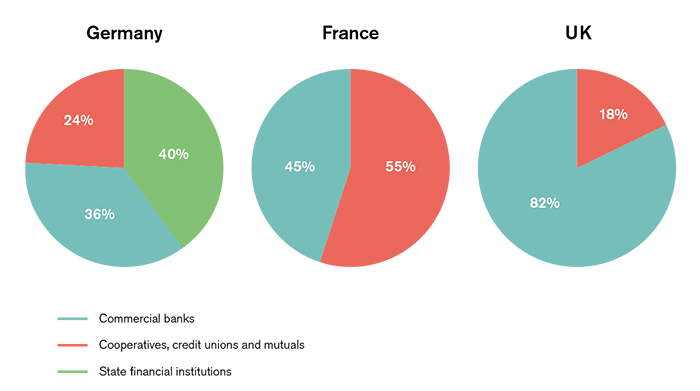

The UK banking industry is dominated by commercial banks – 82 percent of the sector, compared to 45 percent in France and 36 percent in Germany.

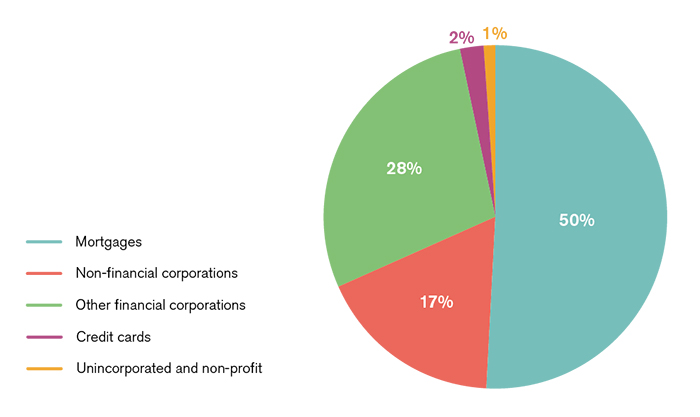

A focus on commercial activity tends to move banks away from so-called ‘risker’ loans towards safer, asset-backed property investments, like mortgages – which account for 50 percent of total bank lending.

Small business lending and supporting vulnerable customers is quite simply more hard work and much less profitable.

Not only are banks failing to provide credit, failing to support growth and expansion in the economy, but they are leaving our most vulnerable high and dry.

The UK government struggled to get money to people during Covid-19

Covid-19 is an insightful case study that shows the shortcomings of government policy and also British banks in terms of how they help – or don’t help – British businesses and vulnerable and marginalised people.

The Government said from the outset that it would ‘stand behind British business’ through the crisis and called on the banks to do the same.

Banks were invited by the Government to perform an essential support function for the receipt of government aid. Yet the Government’s Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CBIILS) proved quickly to be sluggish and complex.

Businesses were struggling – with 6 percent of small British firms having already run out of cash at the beginning of April and 57 percent without enough liquidity to survive the next three months. But only 1,000 loans were distributed nationwide in the first two weeks of the scheme.

These led to revisions, resulted in the Bounce Back Loan Scheme (BBLS) on 1 May 2020. This removed all risk for the banks. Finally, the lending started to flow - with £14.8 billion lent through BBLS in two weeks (4 May – 18 May) compared to £7.25 billion lent via CBIILS in eight weeks (23 March – 18 May)

However, for many SMEs even then the response was not enough. While around 36,000 applications had been approved for CBILS and nearly 270,000 for BBLS, there had also been 130,000 rejected applications. Not to mention hundreds of thousands of incomplete enquiries or SMEs who just couldn’t get the funds in time to keep trading.

One reason for this was that such a small number of lenders were approved for this process. It was disappointing to see the slow pace of bringing fintechs such as Starling Bank on board. The limited choice of lenders put businesses who didn’t already bank with them at risk.

It is absurd (and the opposite of free market principles) that good small, local businesses may therefore have gone under, not because they were bad businesses but because their current account was with the wrong bank.

Local British businesses and entrepreneurs were not prioritised adequately in the Government’s response. The banks’ failures in this regard compounded problems with the Government’s economic policy response. We must learn from this.

Community banking helped countries support businesses during Covid-19

Our research has led us to the view that if we are to overcome these issues, we need to reshape the British banking industry.

We must get more credit into local communities and small and medium sized businesses if we are to truly level-up Britain.

Important lessons should be drawn from Europe and America.

In Germany, after a slow start the government increased guarantees for small businesses from 90 percent to 100 percent with interest rates capped at 3%. There was much less pressure on the big banks to make masses of quick risky decisions as they have a relatively low share of small business loans compared with the local savings and cooperative banks. Germany’s state development bank KfW also played a key role and was quickly able to distribute 8.5 billion Euros in loans to more than 13,000 companies, approving 98 percent of applications.

In the US, 60 percent of the 1.66 million loans to small businesses (worth $300 billion) that were approved in the first round of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) were distributed by the US’s 5,000 community banks.

Why were these countries better able to support businesses during Covid-19? Both have longstanding traditions of regional or community stakeholder banking.

It’s not the first crisis where community banks have made a difference. After the 2008 financial crisis, loans to small businesses declined steeply at big banks but grew relatively faster in community banks.

The benefits of community banks

Our research shows that by pursuing a different business model, community banks bring social and economic benefits in four main ways:

- Having a more diverse financial system makes it more resilient. For local areas, community stakeholder banks provide a ‘cushioning effect’ for regional economies.

- The quality of credit and loans improves, because community banks have better access to ‘soft information’ from personal relationships with local businesses.

- Community stakeholder banks usually have a commitment to financial inclusion, often specifically guaranteeing universal access to banking facilities on equal terms to all citizens in the region.

- The presence of a head office adds an important route for local career progression as an alternative to migrating to ‘the big city.’

How the RSA is working to help establish community banks

The RSA supported the development of a community stakeholder banks in the UK, not just in theory but in practice.

In partnership with a body called the Community Savings Bank Association, RSA Fellows, bankers, economists, movement builders, project managers, researchers and many more from the RSA’s networks and beyond, we have worked to make this happen - pooling the community’s knowledge, expertise, and resources to take the movement forward at a local level.

This work has been referenced in Westminster and the Senedd (Welsh Assembly), and was part of key party manifestos in the 2019 general election.

At an event with Bristol City Council in 2019, Deputy Mayor, Craig Cheney concluded:

“This is a huge and exciting opportunity to bring a whole new model of banking to the UK”

Today, in the UK there are five organisations that are in the process of establishing a local cooperative bank having registered with the FCA.

The most established of these are South West Mutual and Avon Mutual, both of which have completed an initial round of fundraising, developed strong partnerships and secured initial seed funding form local authorities of all stripes. Both hope to launch in 2022.

“We aim to become a key anchor institution supporting the growth of other community wealth building institutions and focused on promoting sustainable and inclusive prosperity for our region” – Jules Peck, Founder Avon Mutual.

Banc Cambria has had initial seed funding from the Welsh Government and is currently developing a road map to launch.

North West Mutual is the latest body to be established with councils including Wirral, Liverpool and Preston collaborating on a bank for the region.

These banks all now face a difficult economic situation due to Covid-19. But the incredible demand we’ve already seen shows that their work must be supported if we want to make sure the recovery leads to more regional equality than we had before Covid-19.

See our 12 recommendations for building banks to level-up Britain and read the report

Join our community and help shape change in a post-Covid world.

Related articles

-

An economy of everyone

Anthony Painter

Anthony Painter describes how a democratic economy - of everyone - might work.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

An excellent article setting out the position the UK finds itself in when the banks still don't understand the need for regionalisation - getting to know the needs of a region which vary tremendously, not providing one answer for all!