Design for Planet, the global gathering of designers during COP26, met to discuss the changes design must make to build a regenerative future. Joanna Choukeir shares her key reflections.

My colleague Josie Warden and I have just returned from the hugely inspiring and provocative Design for Planet festival, a COP26 fringe event hosted by the Design Council, galvanising and supporting the UK’s 1.69 million-strong design community to address the climate emergency.

I cannot think of many moments in design’s recent history – Ken Garland’s First Things First Manifesto in 1963 may come close – when designers came together unanimously to transform the role they will play for our planet’s next chapter. One hundred leading designers in circularity, sustainability and regeneration came together at V&A Dundee, and were joined online by over 5,000 designers from all around the world to re-examine the role design must play in changing our trajectory.

We know all too well that for at least the last hundred years, design has been a big part of the problem. As designer Leyla Acaroglu put it: “Everything that exists in the material world comes from things we have done as designers: the services, products and campaigns.” Discussions about this impact are not new amongst the design community but these few days in Dundee were marked by a palpable shift in both tone and content in four ways, which together signal a step change for the industry.

1. Designing for planet is the central mission of all designers

Firstly, designing for planet is no longer the mission for the few, a choice for a career path, but the only possible and meaningful life path. It is a reckoning that we all have agency in this. Kate Raworth captured this shift wonderfully: “If you are not designing for planet, what planet are you on?” Similarly, Jane Davidson, who championed The Wellbeing for Future Generations (Wales) Act in 2015, called this a time to design for ‘living’. Dr Tayo Abedowale stressed that as designers, "it is imperative for us to expand the brief of our clients and persuade them with evidence to improve the environmental impact of their projects."

2. Expanding the view, back into history and forward into our future

A second shift is an expansion of notions of time horizons and worldviews in how we come to terms with this global emergency. This is particularly important for an industry where designers often have very timebound relationships with clients and the projects they are working on.

Looking back, this is about recognising that the problems we face today are the result of an economic model that has existed for a very short time, compared with the hundreds of thousands of years that people have lived on this planet, and the much longer life of the planet itself. The climate crisis has come about because of the mindsets and systems we have created (especially those of us in the global north) and it can be changed.

Looking forward, this is about expanding our outlook towards the long-term future and the implications of our actions as ‘design ancestors’ on future generations, whom we will never meet. Jane Davidson, called for designing future generations into our thinking: “If we don’t design them into our futures, we’re designing them out of our futures.” The same goes for our non-human relations.

This is also about understanding that the implications of this emergency will hit those in the global south the hardest, and those who have already been working, through indigenous and traditional practices, to replenish, mend, preserve and regenerate our planet. Payal Arora’s poignant talk certainly brought this message home: “not only have we demonised the global south for population growth and depleting resources, we have appropriated their culture and techniques (repair, frugality, subsistence, collectives), and rebranded it as new solutions to fixing the planet.” At the RSA we have been stewarding expanding time horizons and worldviews through some of our recent work with Fellows, such as Stitch in Time, The Long Time Sessions and Reclaiming the Future. In our recent conversation with Melanie Goodchild we explored how to work with the ‘sacred or ethical’ spaces between perspectives and worldviews to learn and develop together.

3. Shifting towards designing deeper

The third shift sensed was a conversational deepening away from visible above the surface issues (the products, the materials, the waste, the emissions) towards the less visible below the surface issues that have been driving and fuelling the climate crisis (what we value, what we think progress is, what we believe, how we behave, what and how we own, what and how we finance, how we relate to nature, and so on).

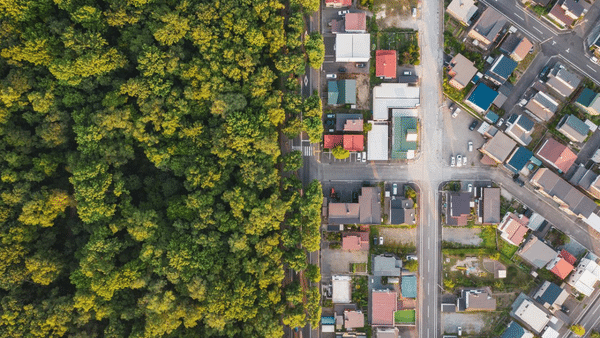

We recognise that we can’t work on surface level issues and events (such as the materials we use and the waste we generate) without deeply examining the mindsets and structures that underpin our value systems and behaviours. Indy Johar from Dark Matter Labs brilliantly describes this as ‘designing for the entangled value’. Our current economies, built on a philosophy of extraction and transaction, have for example, diminished the value of trees – to timber at worst and carbon at best, erasing the entangled and necessary value they already provide for all living systems. In the same vein, Kate Raworth calls for a “need to redesign our economic worldview and mindset”, and Payal Arora spoke about “design’s role to reframe the paradigms and philosophies within which we work”.

Through his concept of ‘Endineering’, Joe Macleod called us all to think about the end of life of products. The challenge of designing good endings goes much deeper. How might we as designers help to end particular ways of life, structures, ideas, products and behaviours that no longer serve us, as well as shepherding in new ways of being and doing.

Musician Nick Mulvey describes these as ‘times of grief and wonder’. The future of design is to help us explore, handle and work with both. It’s a time for us as designers to think about what lies beyond the current and more about the life that will emerge from it. Layla Acaroglu reminded us that there is no such thing as death or waste in nature, life becomes life. Furthermore, Leonie Bell, Director at V&A Dundee, challenged us to think about plastics as the most precious material we’ve ever had.

4. Designing from communities and place

There was a rallying call to move the scale of design back to where it really matters, communities and the places they live in, tapping into communities’ innate capacities, and the regenerative resources nature provides, to imagine and create futures that work for them and the natural ecosystems that surround them. Leonie Bell explained that the biggest role design can play is where people are, in the places where people live. “We need to think of design as a human right”. Immy Kaur, Co-founder of Civic Square, shared reflections from the work she has been leading on with Birmingham communities for over a decade. She believes that change starts with working with people and strengthening their capacities to weave three kinds of matter: dream matter (imagination and creativity), ordinary matter (social infrastructure and the day to day necessary for connectivity in every street), and dark matter (finance, ownership and governance). She concluded her talk with a powerful call to action: “we need to get out of this room as quickly as possible, to find the places we love, we live in and we care about, and start designing from there.”

Entry points for change

The summary above could never do justice to the richness of signals, insights and ideas evoked through the ‘big conversations’ and ‘small conversations’ (as Design Council CEO Minnie Moll put it) that were had at Design for Planet, but here is our best attempt.

The range of topics and issues were broad and diverse, however they broadly align with five possible entry points for transition described in the RSA’s recent Regenerative Futures paper. These are: Rethink leadership, economy, lifecycles, lifestyles and movements. The way we need to rethink all of these elements is by seeing them as ‘entangled’, where the relationship between them matters as much as the things themselves.

We hope that the ripples from Design for Planet, as well as the work of the designers, communities and thought leaders that this festival platformed, reach far and wide for many years to come, to inspire a new generation of designers committed to designing for the transition and for the long-term. As Layla Acaroglu put it: “A message to designers - the system wants to take the agency away from you to make change. You HAVE that agency.”

You can still catch up on talks and panels from Design for Planet by registering for free here.

You can find out more about The RSA’s Regenerative Futures programme and how to get involved here.

Related articles

-

Our yes/no voting system means nothing ever happens

Comment

Peter Emerson

Climate change tells us we must cooperate or die. But where’s the cooperation between political parties? Peter Emerson suggests a radical change.

-

Design for Life: six perspectives towards a life-centric mindset

Blog

Joanna Choukeir Roberta Iley

Joanna Choukeir and Roberta Iley present the six Design for Life perspectives that define the life-centric approach to our mission-led work.

-

Rural and post-industrial perspectives on the just transition

Report

Fabian Wallace-Stephens Emma Morgante Veronica Mrvcic

This report explores how changes to the energy system could impact specific Scottish regions and bring together citizens to collectively imagine better futures.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.