Riley Thorold explains how recent RSA work on public participation can inform a broad shift towards a more active and empowering democracy.

The government’s Levelling Up white paper published in early 2022 was clear in stating the importance of community participation and social infrastructure in tackling spatial inequality. As well as acknowledging the dynamic relationship between economic development and social infrastructure, the white paper set out some encouraging proposals for empowering communities around the UK, including the £2.6bn UK Shared Prosperity Fund and a pilot for ‘Community Covenants’ - agreements between councils, public bodies and communities that would ’set out a driving ambition for their area, and share power and resources to achieve this’.

These are promising steps that can help involve and empower communities in the levelling-up agenda, but discrete proposals and pilots must be complemented by, and contextualised as part of, a much broader shift towards more active and participative democracy in the UK.

Political inequality and disempowerment

Political inequality has received far less attention from social commentators than its sibling inequalities. While we have a growing body of data on health inequality and an established set of metrics and equations through which to analyse economic inequality, political inequality remains relatively unexplored. Admittedly, it defies simple study, referring to disparities in political opportunities, political participation and political outcomes and measuring it requires an awareness of how these interact.

But it is no less harmful because of this complexity. Disempowerment represents both objective and subjective barriers to participation in political and economic life. Political scientists in America have long shown an affinity between political and economic inequality, and Public Health Scotland has led valuable work on ‘power as a health and social justice issue’, demonstrating the correspondence between political inequality and other forms of inequality. What these studies show is that socioeconomic inequality is not the inevitable result of blind economic forces but rather the outcome of unjust political decisions made in unequal democracies.

Political inequality and the levelling up strategy

Tackling political inequality (disparities in political opportunity and political participation) must therefore be central to the levelling up agenda. Any successful strategy for tackling economic and spatial inequality will have to contend with the pervasive, and ever-growing, feelings of disempowerment in places and communities across the UK, particularly those that are most deprived and underserved.

Two of the key ideas for responding to disempowerment in the white paper - growing social capital within communities and devolving power more systematically to mayoral and combined authorities - are both important pre-requisites to tackling political inequality, but neither will be fully successful without robust mechanisms that enable communities to genuinely influence political decision-making on an ongoing basis. This will require a deeper analysis of the interface where the ‘bottom-up’ (community capital) meets the ‘top-down’ (devolution deals): the grey area where participatory and deliberative democracy come into their own.

Participative democracy from the top down

Last year we released Transitions to Participatory Democracy, our research setting out how local and regional democracies can grow and enhance public participation in local governance.

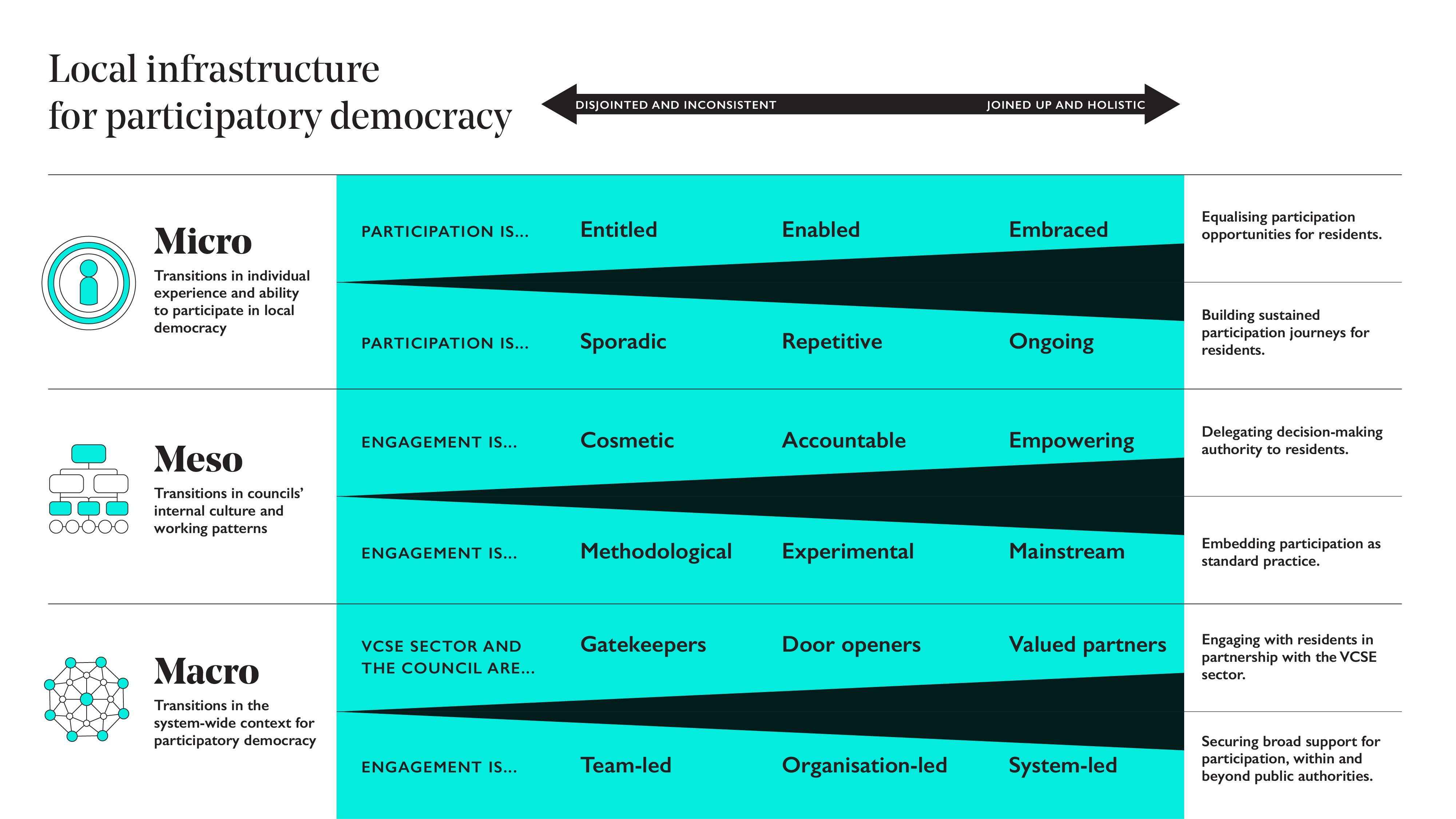

This research highlighted six broad transitions in policy and practice that can help public authorities to develop a local participatory infrastructure to support innovative, empowering, inclusive and impactful forms of participation on an ongoing basis.

These six transitions are set out in the following graphic:

These transitions enable local and regional authorities to build a more robust and reciprocal relationship with communities, in which genuine power is shifted to residents, thereby helping to ‘level up’ political power across the UK.

Participative democracy from the bottom up

However participatory democracy cannot, and should not, simply be a managed project of institutional reform. The charge sometimes made of public authority-led engagement – that it can be too transactional and tightly constrained – suggest some of the limitations of a top-down approach to community empowerment, even when it has a material impact on public policy.

To deliver deeper and more lasting impacts in communities, participatory democracy must also be coordinated and combined with bottom-up programmes of community development.

Our Nechells Knows Community Assembly which took place over two months in 2021 in a small area of Birmingham demonstrates the potential for this kind of coordination. Our ‘community assembly’ model combined deliberative methodologies with light-touch activities drawn from community development practice (such as political education exercises and community organising methods).

The output was a set of 48 recommendations that were presented to a group of local powerholders. But perhaps more excitingly, those who made up the assembly have since set up their own community group alongside other residents. The assembly produced not only recommendations but also a community network that can itself deliver on those recommendations or advocate for other local stakeholders to do so.

Where bottom-up meets top-down

We’re keen to experiment more at the intersection of public deliberation and community development, building on our experiences in Nechells.

Just as some forms of public engagement (including deliberative engagement) can be criticised for being too tightly constrained (often within parameters set by existing powerholders), community development has been criticised for often (in practice, if not theory) lacking political teeth and for empowering well-connected community members at the expense of others.

We think models of public participation that combine elements of both deliberative democracy and community development provide one example of how to address these criticisms, combining the robust recruitment and political efficacy of public deliberation with longer-term ‘social capital’ benefits generated by high-quality community development practice.

There will always be a tension between the ‘top-down’ and the ‘bottom-up’ – this is one of the many reasons why building a participatory democracy is such a complex and demanding task. But we believe bottom-up forms of community development and top-down exercises of institutional reform and public engagement can be in productive tension, together helping to narrow the deep fault lines of political inequality in the UK.

We will continue to push for a more active and empowering democracy at the RSA over the coming months. Keep chekcing back for further updates.

Where do you see the benefits of participatory democracy? Let us know in the comments section below.

Related articles

-

Transitions to participatory democracy

Report

Riley Thorold

This report highlights six transitions in policy and practice that can help local authorities advance and embed local participatory democracy.

-

We have power as a community

Report

Samanthi Theminimulle

This report explores the ability of deliberative processes to give residents more decision-making power and direction-setting in their homes and neighbourhoods.

-

Adaptation nation

Comment

Alexa Clay

The director of RSA USA discusses how a new breed of changemaker is finding ways to strengthen civic fabric and solidarity.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

It is extraordinary to write on levelling up, when a critical point that it is a political programme postulated by a political party that has striven mightily to disempower local government (bar one or two mayoralties) for decades, and which has engendered high levels of distrust in the integrity of its public declarations. The lack of integrity of the PM does not help in that regard. Might I suggest, before appearing to embrace a key programme of HMG, you include amongst critical issues that of gaining trust and engagement from all stakeholders. You might also cast the net wider than a simple declaration in favour of 'participatory democracy' by looking at the voting system and access to voting. How can one participate if government is actively making it more difficult, by adopting policies from the Republican Party in the USA (photo ID for voting) that has negative effects on participation, depsite there being no evidence of any material problem of voter fraud. And in terms of outcomes, perhaps you might throw in FPTP vs. PR as a major issue to ensure percetopns of fairness in outcomes, that would then, in principle, drive a sense of value in participation.

Paul, I could not agree more with everything you've written. I was personally disgusted to see Nadim Zahdawi embraced, welcomed and treated uncritically at last Saturday's event. In no way is regarding these people as part of the legitimate democratic landscape anything but anathema to the values of the RSA. I hope your comments and mine are properly read and digested.

Very much like the diagram you've developed and the work you're doing. We've just recruited a policy fellow to look at how we embed participation in policy making and look forward to learning from your work https://www.cape.ac.uk/policy-fellowship-with-newham-council-improving-participative-policy-making/

This is a very interesting article containing some very interesting thinking. I will now learn more about the Nachells Knows project. Earlier this year, Cordial.World conducted a small survey in South London to learn more about whether people might be interested in earning money, tokens or community rewards for sharing their personal insight and lived-experience. Over 80% said they would. I think Web 3.0 provides alternative incentive mechanisms to attract and retain individual and community contribution in local decision-making and action. Much more to be explored, though, and that's why I'm seeking R&D funding for Cordial World through UKRI and angel investors. I would love to work more with RSA on this area. Thanks for posting Riley.