Regenerative design is an approach that sits at the heart of everything we do. Here, Nat Ortiz, Head of Collaboration and Learning Design, shares more about the practice and its application in our Just Transition for Scotland project.

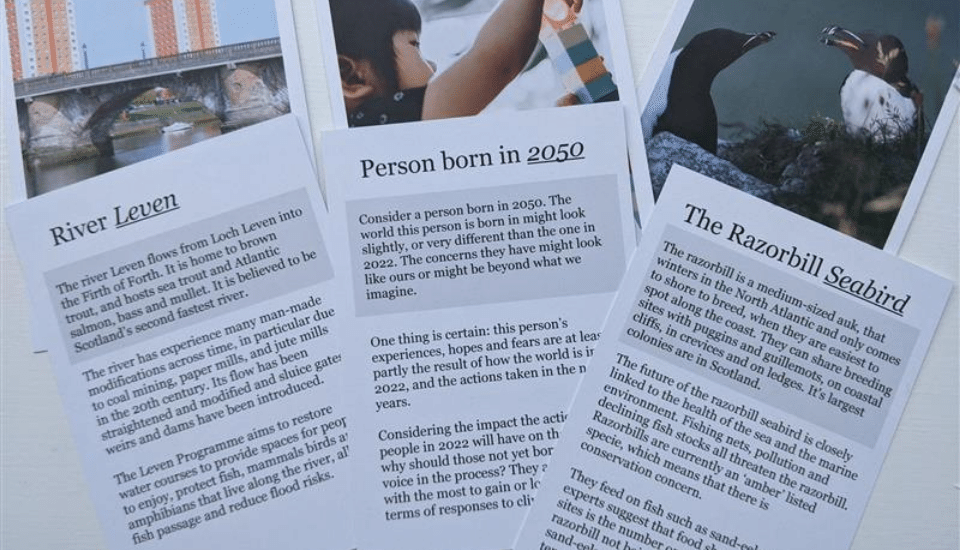

"What might a ‘just’ transition imply for a person born in 2050?"

"What would we prioritise when given the chance to think like the Razorbill seabird or the River Leven in Fife?"

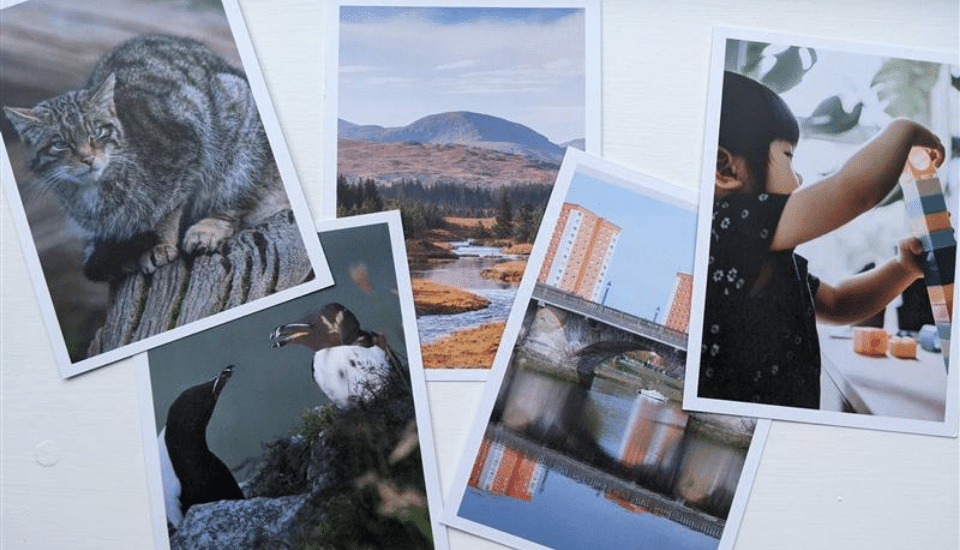

"What would the Scottish wildcat, the 300-year-old oak tree, or the Galloway and Southern Ayrshire biosphere choose?"

These are the types of questions we grappled with when discussing the idea of a just transition with different communities in Scotland. The notion of a ‘just transition’ was incorporated into the 2015 Paris Agreement. It is defined by the Scottish Government as both the outcome – a fairer, greener future for Scotland – and the process that must be undertaken in collaboration with those impacted by the transition to net zero.

The RSA, in partnership with the Scottish Government, has been running a series of workshops to understand citizens’ perspectives on how changes to the energy sector could impact their communities and to collectively imagine better futures. While the complete findings of this work will be published in an upcoming report, the purpose of this blog is to share more about the practice and application of regenerative design through the example of this project.

Don’t always judge the success of changes in terms of cost – rather in terms of human rights, health, impact on people and planet.

Regenerative design as a practice

To shape an equitable future, we must find a new way of imagining our place in a world where everything is connected.

The RSA’s new Design for Life mission is focused on unlocking the potential of people, communities, companies, places and systems to transition towards resilient, rebalanced, and regenerative futures for everyone. Through our work, we are exploring the application of a regenerative mindset. We recognise that in order to address the interconnected social and environmental challenges we face we need to rebalance and restore the relationships between humans, other living beings and ecosystems.

Our partnership with the Scottish Government for contributing to The Just Transition Plan opened up an exciting opportunity to apply regenerative design and bring to life some of its key principles. Design that:

- is inclusive and collective

- starts with place considering the different elements that sustain life

- invites us to think holistically and see the interconnections in the relationships we hold and create

- encourages us to imagine, reflect and act with a long-term perspective

So how did we do this in practice and what were some of the insights that it brought to our work?

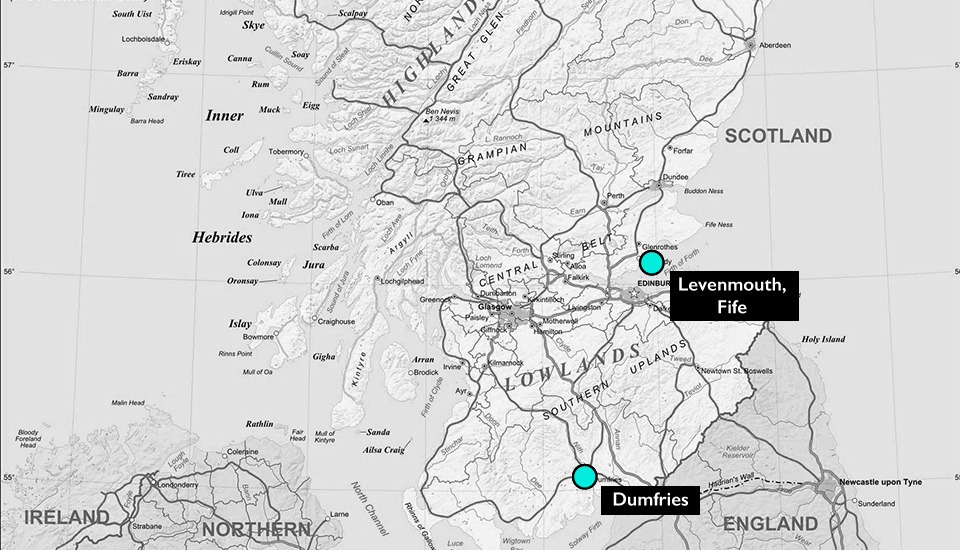

To put these principles to practice, we designed and ran workshops in distinct places and with diverse audiences. In this blog, I’ll be referring, as examples, to the workshops that took place in two different places:

- Levenmouth, Fife - an old mining area on the north of the Firth of Forth heavily impacted by the transition away from coal.

- Dumfries - the old market town in Dumfries and Galloway, now a predominantly rural area.

Just transition rooted in place and context

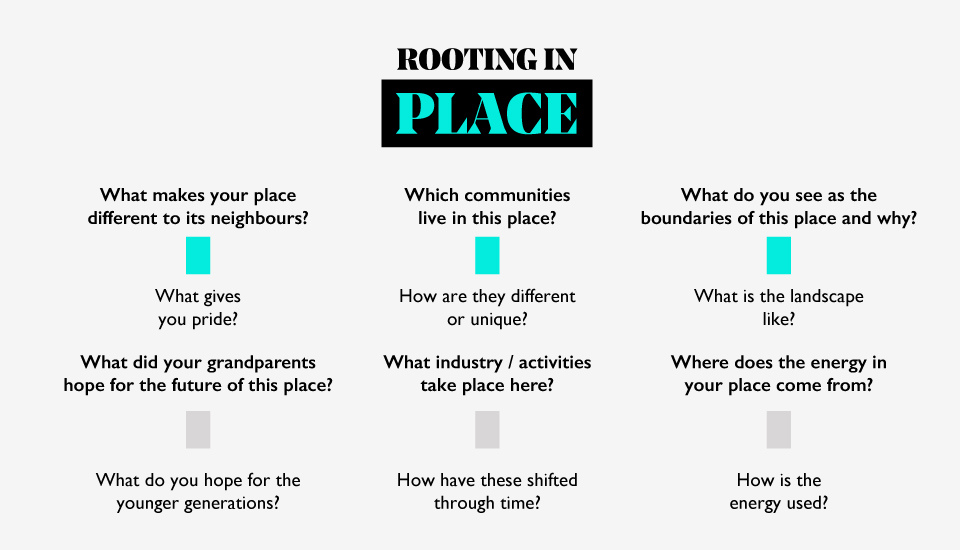

To recognise and identify the unique qualities of people, places and communities, we began the workshops with a set of questions. These questions aimed to surface the lived experience of the participants as well as the history, assets, resources, ecology, and potential of the place.

We heard a range of powerful answers. Some people voiced a sense of togetherness and pride in their community, their hopes and ambitions for change. We learned about the symbols (both natural and human-made) that represent Dumfries and Fife, and heard different ideas about the places’ boundaries through childhood memories of trips ‘elsewhere’. We heard inspiring stories about past generations and visionary residents; we remembered industries and communities that have come and gone and what life used to be like around the docks in Methil in the 1930s.

Rooting in place helped participants and facilitators to listen and acknowledge, respect and appreciate the diversity of perspectives in the room. Moreover, through these conversations, we began to map interconnections across concerns, interests and motivations for being part of this transition. We identified common themes and potential areas of tension as a shared starting point for the day and an anchor for further discussions.

Some of the themes that surfaced included:

- the strength of community relationships

- the challenges faced following the end of mining

- local energy-generating potential and access for communities

- power imbalances in decision-making processes

- local initiatives and approaches to innovation

- the beauty and pride held in natural assets

We sit here, right next to us we have what was the largest wind turbine in the world, it’s so present in our place yet the community has never had access to the energy or the benefits it generates.

Moving beyond a human-centred or anthropocentric lens to consider the nested natural and social systems in which a community is situated is a key part of this work which can help prevent a superficial approach to a regenerative practice. Making therefore a regenerative process or goal unique to the place where it sits.

A seat at the table for wildlife, natural landscapes and future generations

What if the just transition considered and made explicit the interdependence of issues and the impact on the economy, communities, future generations and the living world?

Our systems are currently organised in unbalanced ways. The overarching economic and governance models hold an extractive relationship with ecosystems and other living beings. Design also has been too ‘centred’ on humans and the power asymmetry of this dynamic has brought our planet to a state of crisis. However, despite this, regeneration has occurred naturally for billions of years, indigenous cultures around the world are living proof of how we can learn a more balanced way of relating to nature, seeing ourselves as part of it. Our work needs to make visible the connections and interdependencies of people and other living beings so that we can act as stewards and create conditions that will be beneficial for all life.

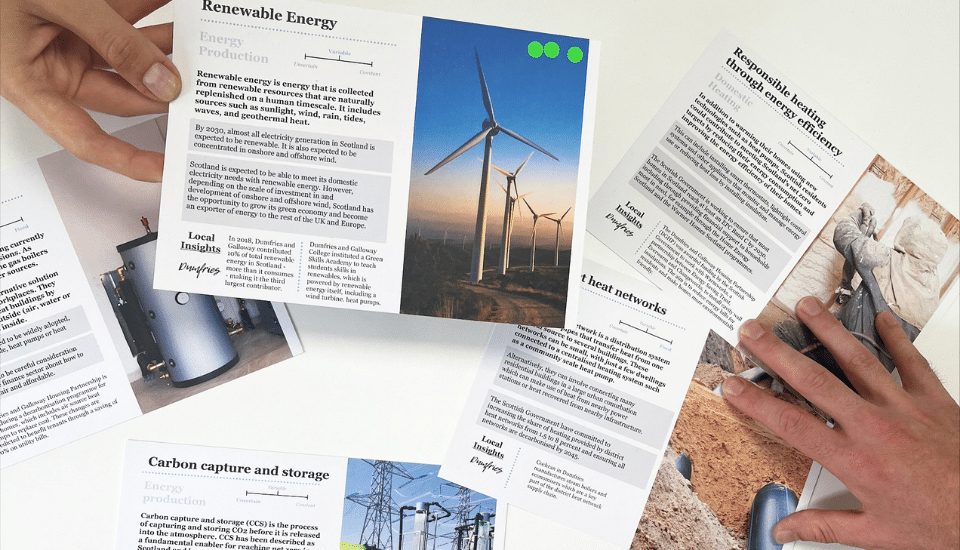

To help us identify and explore the implications of transitioning towards technologies that might shape a new energy system, we designed a set of driver cards. The cards described and clarified specific topics such as energy production from renewables and hydrogen, domestic heating, transport shifts, and negative emission technologies. The cards also included information about the wider impact of the transition, such as new jobs or skill shortages, land availability, cost-effectiveness, fuel concerns and water use, as well as local implications directly related to the places where we were holding the workshops.

Bringing a regenerative lens, people were encouraged to discuss their perspectives, and to advocate for and consider the interdependences of the relationships we hold with the ‘more than human’, the natural world as well as the responsibility we have as stewards of future generations. We took inspiration from others in the space who have written about life-centred design, Superflux, The Long Time Project, Moral Imaginations and invited participants to think about what this transition might imply for the person born in 2050. What would we prioritise when given the chance to think like the Razorbill seabird or the River Leven in Fife? What would the Scottish wildcat, the 300-year-old oak tree, or the Galloway and Southern Ayrshire biosphere choose?

Balancing interconnectivity

Excitingly, participants weren’t scared to engage with these provocations and challenge themselves to think more long-term. Insights surfaced on the importance and urgency of balancing the interconnections and relationships between human and non-human.

A discussion about the 300-year-old oak tree that sat a few metres away provided a way to transport us to the past and collectively reflect on industries, such as mining, and how they impacted the local habitat and farmland; and logging/forestry and the effects on biodiversity, infrastructure and roads. Then it brought us back to the present to reflect on the local, national and global challenges we face and sent us to the future by looking at how these can be tackled expressing the desire to witness a transition that gives power back to the community.

We also heard:

I wanted to have the perspective of the Razorbill but I’m afraid with the urgency we have and the changes that are required, it won’t be alive anymore.

Representing the wildcat, (and in relation to our homes when discussing responsible heating), in my case, better climate will mean fewer droughts, a safer home for us.

I work in the offshore hydrogen industry because my grandad repurposed his fishing boat in 2025.

We’ll be sharing more detailed findings in the future but some common themes emerged among participants in Fife and Dumfries:

- The need for better connectivity, accessibility, affordability and infrastructure for transport. People saw transport as a key part of connecting communities with each other and supporting life within the community.

- The idea of a 20-minute neighbourhood felt relevant in both places, with the desired shift towards local production and consumption that will benefit humans and the natural world.

- Shifts in domestic heating were seen as desirable in both places, but there was an acknowledgement that sometimes individuals could not make these shifts themselves, especially private or social renters. Another barrier was the high upfront cost of introducing these changes, an issue that current subsidies are not solving because of how they are structured.

- Both places recognised the importance of renewable energy production but were concerned the community might not see any real benefits from changes in their local area, especially in terms of onshore wind power.

Designing from a hopeful vision of the future

The future is not pre-determined and by creating spaces where we can exchange ideas we can collectively envision a hopeful future. A future we want to be part of shaping.

Bringing active hope to face the challenges we have ahead, and co-creating visions can help us step outside the limiting beliefs that compounded the problems regenerative design is trying to address and build relationships, momentum, solidarity, and a commitment to realise the change.

We closed the workshops with a reflective and creative session about the future. Inspired by The Thing From The Future, participants were briefed to imagine and create stories or metaphors that are both plausible and aspirational for the local area. They created speculative newspaper headlines, objects and postcards from a desirable future. Many of these images felt regenerative, exploring visions of self-sustaining communities, and new ways of living in greater harmony with nature.

I would like to see a future that is equal, where everyone is able to afford to be warm, to travel where they need to without adding pressure to the planet.

For me, it’s about Methil as a close-knit community again, the docks busy again not by coal but by renewables with plenty of local employment and opportunities rooted here.

The river Leven to be clean, with the salmon coming back!

Here are some images of what was created:

We will publish a blog in the upcoming weeks that expands on participatory futures and shows lots more wonderful ideas and illustrations. Stay tuned.

What’s next for this work?

We will continue to deliver a set of workshops in the coming months including one tailored for young people and one for people with disabilities. We’ll produce a report that will help inform the Energy Strategy and Just Transition Plan that the Scottish Government plans to publish in the autumn. This plan will act as a guiding document for public and private sector activity and aims to ensure the active role that everyone can play in the transition while identifying and mitigating economic and social justice which may be exacerbated by climate action.

Through projects like this, we aim to build capability and reciprocity, work with people to create shared ownership of challenges and find shared solutions. Evidence demonstrates that enabling participants to build their imaginative capacity can lead to a greater sense of agency and optimism about the future. We know that considering people’s lived experiences is crucial to design better plans and can build legitimacy in policymaking. We also know that to create an equitable future we must find a new way of designing; a design approach that helps us to imagine our place within the world, where everything is connected. We know that some of the methodologies applied in this example aren’t new or necessarily groundbreaking but the insights that came out of these workshops were different and were enriched by a regenerative design approach.

We are at a stage of learning, experimenting, and testing ways of designing regeneratively and are very appreciative of the people who are supporting and inspiring us to do this work including those in Fife and Dumfries. Our Design for Life mission motivates us to create the conditions, share practices, voice different stories, and convene in ways that enable us to collectively continue to shape this work into the future.

Reflecting on this work, regenerative design approaches and how this practice and community are evolving we want to collaborate with partners and practitioners to further explore:

- How we better engage with communities in places in ways that help build power and better convene people with diverse perspectives.

- How we better listen to the voices of people as well as the landscape that makes a place unique to define collaboratively what regenerative means in a specific context.

- How we better design nature activities and/or embodied experiences that can help people empathise, sense and perceive the interconnections we hold with the more than human.

- How we maximise our potential as an organisation to influence partners to adopt regenerative design principles in their work.

- How we best communicate our learnings and work openly with others towards the shared mission of a resilient, rebalanced and regenerative future for everyone.

- How do we design different evaluation tools and metrics for regenerative design? How might we measure the health of people and nature together?

Interested in collaborating with us in our work? Can you see yourself as a prospective partner or practitioner who can help us explore similar projects further? We want to hear from you! Leave a comment in the box below or email Nat via: [email protected]

Related articles

-

Regenerative Futures

A future where humans thrive as part of the Earth’s ecology.

-

Empowering citizens to shape a just transition for Scotland

Blog

Fabian Wallace-Stephens

We're hosting a series of participatory futures workshops over summer 2022. Join us to explore how changes to the energy system could bring citizens together to collectively imagine better futures.

-

Regenerative Futures: From sustaining to thriving together

Report

Josie Warden

This positioning paper explores ways in which taking a regenerative approach can help address the complex challenges of today.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.