As COP15 draws to a close with more historic pledges made by nations, this time to protect our planet's biodiversity, Adana Shallowe, RSA Senior Global Manager, looks back at the other key Conference of the Parties event this year - COP27 - and asks if its commitments go far enough to protect our climate.

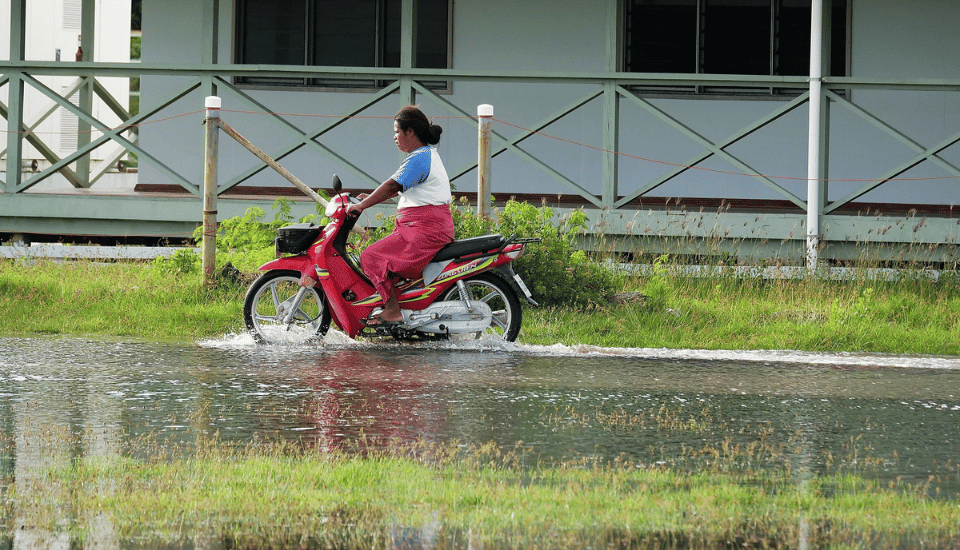

In 2017, I wrote a blog entitled Climate change: beyond the boundary. In it I lamented that, in spite of the burden felt by small island developing states, which are at the epicentre of the climate emergency, little has been done to address the financing of damage brought to bear by climate change.

Now, in November 2022, at COP27, the climate change conference in Egypt, and seven years after the Paris agreement, the most significant global climate agreement to date, the global community has created the Loss and Damage Fund. This is a historic achievement and the result of decades of advocacy and diplomacy by small island states and other vulnerable countries. For the first time, advanced economies have tangibly acknowledged the inequities of the climate emergency by providing funding for rescue and rebuilding efforts after damage and compensation borne by the most vulnerable nations.

This is significant to many small island states.

Small island states are characterised as:

- having populations under 1.5 million

- being small in geographical size

- having limited resources

- having open economies relying mainly on foreign trade as a key component to economic growth and development

- being especially vulnerable to economic shocks and susceptible to income volatility if there is a decline in a major industry

- more likely to be affected by natural disasters such as hurricanes, droughts, typhoons, and volcanic eruptions.

The consequences of the climate emergency for these countries on the front line inevitably disrupts their economic security and typically sets in motion an economic crisis. Take, for example, the hurricane season of 2017. Hurricanes Irma, Jose, and Maria (all category four or five) spiralled through the region leaving havoc and causing colossal damage in their wake. In addition to the human cost, according to Climate Analytics, across the Caribbean region, damages of approximately USD10 billion were estimated for Hurricane Irma alone.

Imagine if this happened year after year after year. What then?

Loss and Damage Fund: not radical enough

For these reasons the Loss and Damage Fund is not only historic but also transformative for so many of these states all over the world.

However, given our current reality, more radical action is urgently needed.

At the COP27’s closing of Plenary, Simon Stiell, the newly appointment Executive Secretary of United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) reminded the delegates that we are in the critical decade of action.

The UN Climate Change report released ahead of the conference in October this year indicated that:

The combined climate pledges of 193 Parties under the Paris Agreement could put the world on track for around 2.5 degrees Celsius of warming by the end of the century.

To meet the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C (by reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 45%), the global community must develop adaptation solutions to respond to climate change's current and future impacts.

In reviewing the missives from this year’s conference, one cannot help but sense a weird resignation that the extent of change is now inevitable. Facing this existential threat, notably our biggest challenge to date, many countries in the global community are unwilling to think creatively, to compromise and coordinate robust climate action policy. However, in some instances countries are significantly constrained by what can be done to finance climate adaptation projects due to the conditions placed on them by international financial institutions.

Financial and ecological instability

These institutions typically equate financial stability to a country’s ability to manage its debt (ratio of total debt to annual GDP) without adequately considering climate risk in its calculations. In 2021, the International Monetary Fund considered 17 small island developing states as being at ‘high risk’ of debt distress. How can a small island state rebuild and recover following a category four or five hurricane and still meet its fiscal obligations especially if it is already heavily indebted? This is impossible to do when the frequency and severity of hurricanes have only grown because of climate change.

Other countries like Barbados are considered too rich to qualify for development aid in spite of its inherent vulnerability to climate change. This prohibits access to discounted loans from international financial institutions leaving them to resort to private capital markets – private banks and hedge funds - to borrow much-needed funds. Imagine that!

Other small island states that can access concessionary loans can still not meet debt payments over the long term.

So, despite this historic achievement at COP27, we haven’t yet scratched the surface in terms of addressing the root causes of climate change and centring justice and equity when it comes to climate finance and how international financial institutions operate.

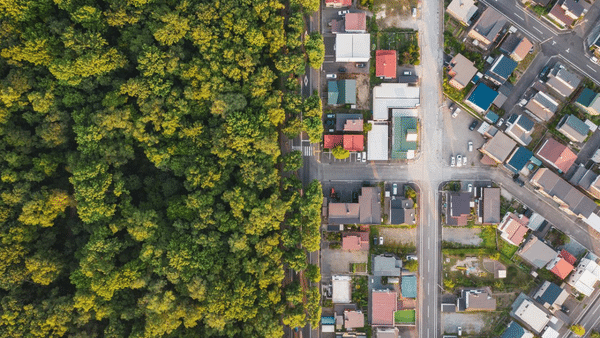

We ought to view the atmosphere, oceans and seas as our global commons which are all under threat (by these root causes) and everyone – countries (big and small), multinational corporations, international financial institutions, communities, and citizens - must all share the responsibility and costs of adaptation. To do anything else is to risk our own lives and mortgage that of future generations.

In the end, we are all islands in one common sea.

What are your views on the outcomes of COP27? Do you feel the commitments from member nations could have gone further? Is it enough to set up a loss and damage fund for small island countries on the frontline of the climate crisis? Let us know in the comments below.

Related articles

-

Our yes/no voting system means nothing ever happens

Comment

Peter Emerson

Climate change tells us we must cooperate or die. But where’s the cooperation between political parties? Peter Emerson suggests a radical change.

-

Design for Life: six perspectives towards a life-centric mindset

Blog

Joanna Choukeir Roberta Iley

Joanna Choukeir and Roberta Iley present the six Design for Life perspectives that define the life-centric approach to our mission-led work.

-

Rural and post-industrial perspectives on the just transition

Report

Fabian Wallace-Stephens Emma Morgante Veronica Mrvcic

This report explores how changes to the energy system could impact specific Scottish regions and bring together citizens to collectively imagine better futures.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.