The cost-of-living crisis is forcing schools to go above and beyond as they support their communities. Using real-world teacher survey responses, RSA Researcher Nik Gunn explores the knock-on effects for youth social action.

As our Third Benefit project on youth social action nears completion, we have partnered with TeacherTapp to understand how English primary and secondary schools have reacted to the difficult economic circumstances faced by their communities. This complements the survey we ran in Autumn 2021, which explored the experiences of educators delivering youth social action in their schools, as well as intersecting with our work with the Health Foundation on young people’s economic security.

TeacherTapp is a daily survey app that reaches thousands of teachers across the country and poses questions on a range of educational topics. At the end of January 2023, we were able to ask over 2,000 primary and 5,000 secondary school teachers about their school experience of the increasing cost-of-living crisis.

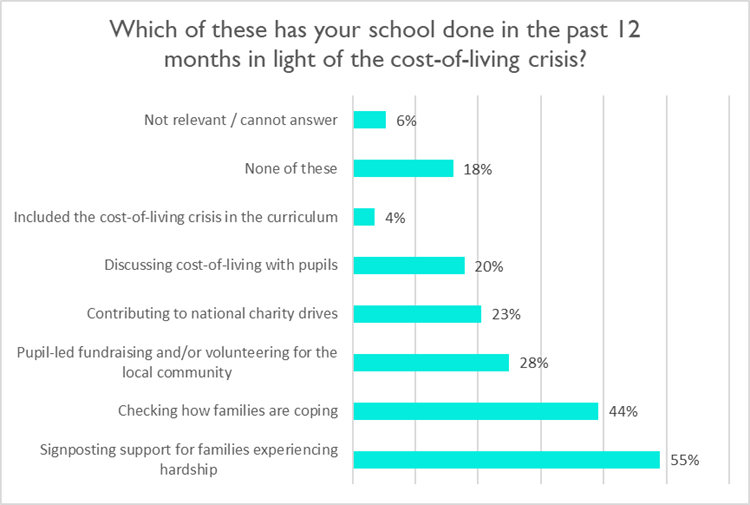

Schools are going the extra mile for their local communities in terms of support at a time when they are under a huge amount of pressure, but it’s clear there are deep structural inequalities at play. Most schools are signposting support for families (55 percent) or checking in with families experiencing hardship (44 percent). This is especially true of schools where many pupils receive free school meals (FSM). 20 percent of schools discuss the cost of living with pupils, but only 4 percent are embedding the cost-of-living discussion in their curriculum. There are structural reasons why integrating the cost-of-living into the curriculum might not be viable for many teachers, however. Given many pupils will themselves be experiencing the effects of the crisis, integrating the subject into classroom teaching could prove challenging.

When we compare primary and secondary schools, a few differences emerge in terms of the sorts of activities that schools can engage in. Primary schools are far more likely to be signposting support and checking in on families, while secondary schools are a bit more likely to have charitable or pupil-led action. In our research interviews, primary school teachers have highlighted the fact that engaging pupils in youth social action can be difficult when their communities might be suffering.

Civic learning opportunities and structural inequalities

Youth social action provides important benefits for pupils in terms of outcomes, especially around the development of crucial lifelong skills such as problem-solving. As our qualitative research is revealing, it also connects young people to their community and gives them a real sense of agency in being able to effect change.

For teachers, participating in youth social action alongside their young people ignites their passion for teaching and sense of purpose. Data from the University of Kent’s 2023 Educating for Social Good study also indicates that primary schools are increasingly steering away from asking pupils for financial contributions, instead focusing on other ways children can give their time or skills via social action. It’s important, then, to ask how the cost-of-living crisis might be impacting the provision of civic learning opportunities within English schools.

There’s an unequal distribution of pupil-led activities, with private schools being able to provide more opportunities for youth social action. This inequality of opportunity is backed by Kent’s Educating for Social Good report. There’s also a structural dimension to this: one striking finding from the above is that private schools while facilitating more social action, are far less likely to be reporting checking in on families or signposting support compared to their state-funded counterparts (respectively 12 percent vs 48 percent and 12 percent vs 59 percent).

Disparities between state and private schools

This is to be expected given private schools serve communities unlikely to be experiencing the same hardship as those served by state schools. This is born out in the Educating for Social Good data, where state schools reported that the financial constraints of the families they serve (66 percent of state schools, vs 12 percent of private) and the fact that some pupils might be the beneficiaries of charity themselves (21 percent, vs 5 percent private) were key barriers to facilitating youth-led social action. Our qualitative research for Third Benefit backs this broader picture, with several teachers discussing having to consider the tough circumstances their pupils and wider community face.

These disparities are replicated when we focus on the primary phase. Private schools are more likely to report contributing to national charity drives (34 percent vs 20 percent) and pupil-led fundraising or volunteering in the community (38 percent vs 20 percent) than state schools. This disparity between private and state primaries is important in the context of inequality of distribution of civic learning opportunities. Our qualitative research with teachers at state primaries has repeatedly highlighted that lack of resourcing is a constant issue in being able to provide high-quality youth social action, especially in light of continuing spending cuts. One school reported dedicating a lot of effort to bringing in external funding to get projects off the ground.

When we refine the results according to other factors, we can see how inequalities manifest. If we consider the number of pupils receiving free school meals (FSM), we find that schools in less well-off areas (fourth quartile) aren’t able to facilitate the civic action they might want to. Schools serving poorer communities were less likely to be able to do charitable drives (20 percent) or pupil-led social action (24 percent) compared to those in the wealthiest quartile (25 percent and 31 percent respectively). These dynamics, with more affluent areas being able to facilitate more social action—often linked firmly into the curriculum—are replicated in the University of Kent study.

Cost-of-living affecting school youth social action

As important hubs within their localities, schools are doing their best to support the communities they serve with limited resources and increasing pressures. Our results, in conjunction with the University of Kent’s work, also reveal that the knock-on effect of this is that state schools, and especially those in poorer areas, are not able to provide the sorts of youth social action that we know can have a positive impact on children’s development.

In June we’ll be publishing the Third Benefit Toolkit, which is a culmination of the RSA’s recent work on youth social action. While the picture painted in this blog is a challenging one, the toolkit will celebrate the amazing work that teachers, pupils and communities are doing around civic learning. Through in-depth interviews, workshops and wider survey data, we’ll be showing how primary teachers have been doing youth social action in a range of different contexts.

What statistic above is the most shocking and what can we do to help challenge the issue it illustrates. Let us know in the comments section below.

Related content

-

The Third Benefit

Can participation in social action by our young people yield benefits beyond those of the individual and their community?

-

RSA Catalyst Awards 2023: winners announced

Blog

Alexandra Brown

Learn about the 11 exciting innovation projects receiving RSA Catalyst funding in our 2023 awards.

-

Investment for inclusive and sustainable growth in cities

Blog

Anna Valero

Anna Valero highlights a decisive decade for addressing the UK’s longstanding productivity problems, large and persistent inequalities across and within regions, and delivering on net zero commitments.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.