Earlier this week, here at John Adam Street, I helped facilitate a seminar sponsored by Hanover Housing on the topic of responses to societal ageing. The housing group commissioned nine think tanks to write essays looking at different aspects of the topic . Included was the RSA with a provocative paper on age and attitudes entitled ‘sex, skydiving and tattoos’ .

After listening to our own Steve Broome and also Baroness Sally Greengross from the International Longevity Centre UK and Andrew Harrop from the Fabian Society, I offered some broad reflections of my own.

The grey dog barks but doesn't bite:

Population ageing is arguably the biggest rapid demographic shift to occur in modern human history. You would have thought it would lead to massive changes in attitudes, expectations and practices. But, as yet, change has been marginal. Casual and institutional ageism is still deep and widespread. With 400,000 old people in residential care in England alone (a form of care surveys show almost none of us want for ourselves), we still accept that a high proportion of older people will lose almost all their independence and dignity as a price of becoming fail. And despite the best endeavours of organisations including the Design Council and NESTA the scale of innovation in institutional redesign and service delivery is also pretty limited given the scale of the challenge. It is a genuinely tragic irony that the group that most needs changes in attitudes and practices is widely caricatured as the most resistant to change.

The struggle for older people’s liberation requires a clearer narrative:

Half the time it seems older people and their champions are challenging negative stereotypes of elder vulnerability while the other half is spent special pleading for pensioners. We need to fasten to the same narrative and it should be something like this: the final third of life can be our best, people are wiser, more rounded and more responsible and they have more free time for themselves and to contribute to society. Indeed, wellbeing surveys show that older people who are healthy and have loved ones near at hand are happier than other age groups. The scandal is that, as a result of ageism, neglect and social inertia, so many older people are denied the opportunities of a great later life.

Give with one hand to take with the other

Liberation struggles involve giving up the condescending privileges that come from second class status in exchange for equality and respect. In the early days of feminism, for example, many women felt threatened by the idea of losing the concessions which resulted from being viewed as the decorative, domestic, weaker sex. Elder liberation means rejecting the special privileges which are the flip side of social stigma and marginalisation. The Government’s proposal to introduce a limit for the care costs shouldered by individuals funded in part through increasing inheritance tax thresholds is a sign of things to come. Given the problems faced by younger generations, there is no ethical or political case for further transfers from young to old. The politics and the economics go together: If we abolished special hand outs and tax breaks for pensioners (excluding the basic state pension), we could massively improve the quality of care and fund a range of programmes to open up new opportunities for older people.

Invest in innovation

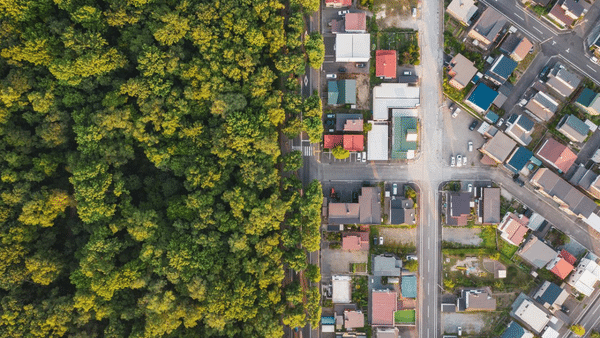

The onset of societal ageing has led to some important inventions. Circles of care and the University of the Third Age are two examples. Yet, as a whole, innovation has been marginal. In major policy areas like health and social care, housing, education and employment we need major system change and the invention of a swathe of new institutions, especially those created by and for older people. National and local government should make investment in innovation for ageing a priority with the core aim being to shift the perception and reality of ageing from a social burden to being a civic resource.

In the end society will have to adapt to getting older. The question is whether we do it quickly, positively and creatively or whether millions more people have to suffer being patronised, marginalised and neglected before we get our act together. Older people getting noisier and better organised won’t on its own solve the problems but it is a vital, and currently absent, driver of change

Related articles

-

Design for Life: six perspectives towards a life-centric mindset

Joanna Choukeir Roberta Iley

Joanna Choukeir and Roberta Iley present the six Design for Life perspectives that define the life-centric approach to our mission-led work.

-

Inventing meaning and purpose: a politics award for our times

Ruth Hannan

Ruth Hannah is inspiring you to submit your creative and courageous political project to the Innovation in Politics Awards 2022.

-

Open call: Creative collaboration and collective imagination research

Hannah Webster Ella Firebrace

Learn more about the UNBOXED: Collective Futures open call; inviting you to submit what you are doing to help shape better futures for people and planet.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.