The RSA has a new way of thinking about the world and the impact we want to achieve. We call it the Power to Create. It was the subject of my annual lecture, of this RSA Short and of many blogs by my colleagues, for example this excellent recent post by Adam Lent (which prompted me to contribute to his crowd funding campaign). As we had hoped, when people approach a set of ideas positively but with different perspectives those ideas can develop in many interesting ways.

Over the last couple of days, speaking to various people now back from Manchester, I have questioned the tone and content of Labour’s conference, particularly the assumption that most people are victims who can only be saved by the benign power of the central state. In defending the conference and critiquing the Power to Create my Labour friends’ key argument can be summed up as; ‘that’s all very well, but what does it mean to a constituent with a badly paid insecure job or to an exhausted carer relying on ever more meager state support?’

Their issue is not with the idea that everyone can and should live creative lives but with the gap between this idea and the practical reality faced by millions of hard pressed people. How can Government help people live creatively when it is hard enough helping people survive? This is a serious point but I think it can be addressed.

As I have argued, the Power to Create takes a somewhat wary view of central Government interventions: social policy needs to be less about trying to change people or achieve particular outcomes for them and more about enabling more people to be able to take control of their lives. Civic engagement and mobilisation, often starting from the ground up tend to be more powerful tools for enduring change than merely pulling policy levers. Power should be decentralised to the lowest practical level. The experimental, iterative, user-centred approach of designers is more suited than traditional policy making to solving problems in today’s ever faster changing, ever more complex world.

To take three examples from the Miliband speech; more new homes, a higher minimum wage and more apprentices all sound like good things, but experience tells us the pursuit of the specific goals of 200,000 more houses, £8 an hour and equivalence with graduates may also have unwanted side effects. Might it be better to aim for greater parity between housing tenures, to focus on choice and quality in young people’s education rather than a quantitative target (other similar educational targets have had at best a mixed record of success), and to work with business and localities to develop a more flexible minimum wage reflecting industrial and regional differences?

None of this means we don’t need national policy, nor that it doesn’t matter what that policy is. For example, on the deficit I tend to agree with Labour that the Treasury should set a slightly less demanding target (excluding capital investment from the deficit measure), partly because the NHS and social care are close to collapse (although here again it is not clear why the Labour leader found it necessary to specify exactly how many jobs and of what types are going to be centrally mandated for the extra funds).

The Power to Create recognises that we need some big change to facilitate a world of many smaller changes. As Adam argues, the ideal of Power to Create demands a comprehensive policy for wealth and assets, redistributing hoarded and often unproductive assets at the top and using the receipts to help the third of people who effectively have no savings and thus too little opportunity to change the direction of their life. Equally, we need elected Government to use its mandate to tackle concentrations of corporate power.

So the right type of policy, directed particularly to increasing civic capacity and individual autonomy in poorer communities is important to the Power to Create. But progress does not have to wait for a benign national policy environment. There are many practical things we could do tomorrow to enable people to have more control and more meaning in their lives.

At the RSA we are putting ever more focus on institutions as how they work can be a big barrier to, or enabler of, human creativity. Organisations that are dynamic, mission driven and where employees are encouraged to work together in teams with significant autonomy succeed through generating the Power to Create in their employees. Given that only one in five British managers have had management training it is perhaps not surprising that over third of workers say their talents are not being used at work or that national productivity is so low (in my experience the way people are treated within the higher echelons of political parties and Whitehall all too often exemplifies bad practice).

And when it comes to public services, what matters to people is not just what is provided but the way it is provided. The RSA promotes the principle of social productivity – that public service interventions should be judged by the degree to which they enable people better to contribute to meeting their own needs. Jocelyne Bourgon and her colleagues talk about civic effects such as growing capacity in communities being as important as more traditional public policy outputs. Even if there was no national policy change for five years a more collaborative, creative, open ethos in national and local government could still reap impressive results.

Which leads to a final response to the charge that the RSA’s thinking is too abstract and idealistic. As well as suggesting a set of broad goals to pursue, the Power to Create also helps describes a set of principles to apply today. It means a commitment to live creatively and to see that potential in every other person, living up to our capabilities and trusting in the capabilities of others. Perhaps the most underwhelming aspect of Ed Miliband’s speech was that at no stage did he seem to feel he could trust his audience – in the conference hall or in the country – to deal with anything that was intellectually, politically or personally challenging.

Which takes me back to the beginning. When I made all these arguments to my Labour friend she replied; ‘but people don’t want challenge, they want hope’. To which my answer is this; it is not hope that leads to action but action that leads to hope. The party political model of change tells us to rest our hopes on the right people getting into office, the Power to Create is a call to action starting right now.

Related articles

-

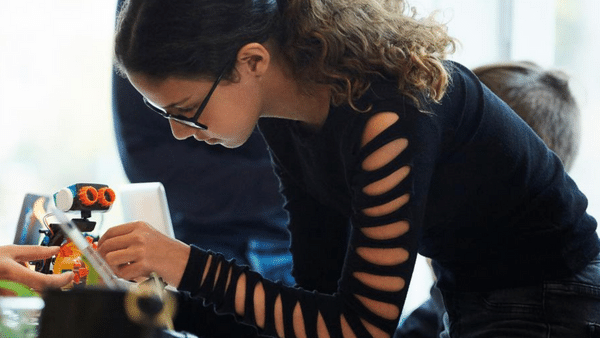

Design mentors: supporting innovation in young designers

Milla Nakkeeran

As we conduct our mentor visits for the 2022-23 Pupil Design Awards read why the role of design mentors is so vital to young innovators.

-

RSA Catalyst Awards 2022: Round two winners announced

Beth D'Elia

Announcing the eight innovation projects receiving RSA Catalyst funding in round two of 2022's awards.

-

Recognising reciprocity

Al Mathers

Al Mathers, former RSA Director of Research and Learning, explores the importance of introducing reciprocity into the work of social change organisations like the RSA.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.