I spend a lot of time talking and reading about organisations and systems; why they don’t work and how they could work better. Something has dawned on me which is both rather obvious and potentially powerful.

Why don’t local public sector organisations collaborate effectively? Why isn’t a large corporation able to inspire its employees to be more proactive? Why are large political parties such unattractive and unpopular institutions?

These problems require changes in the way organisations are led and structured. But if we start with the question of change at the top we are likely to end up advocating reforms based on what hierarchies can accept rather than what might be truly transformational to people’s experience. Here are a couple of examples, both broadly applying the adaptation of cultural theory laid out in my 2013 annual lecture. The Electoral Reform Society has published an interesting short pamphlet entitled ‘Open up – the future of the political party’. Whist I agree with much of its analysis, I think it is guilty of viewing the problem of large parties through a structural/policy lens rather than thinking more deeply about people and what motivates them. An alternative starting point might ask why, apart from career ambition, someone would engage in party political activity. The answer might be threefold; people join political parties to contribute to making the world a better place, to learn and develop as a person and to have fun.

From this starting point it is pretty obvious why party membership and local activism have declined while background levels of volunteering and community activism have remained constant or risen. Going to a local constituency meeting of the Conservative or Labour party is generally not much fun, offers few opportunities for personal development (unless you want to get fit by pounding streets on a leaflet delivery run) and provides only a very attenuated sense of making the world better (although this feels a little more real at election time).

Contrast this with ‘Good for Nothing’, a rapidly growing initiative based on people self-organising into groups which hold ‘gigs’ to develop innovative ideas to improve their local communities. This video is all about fun, personal development and immediate impact.

So rather than the ERS’ broad injunction to parties to ‘be more open’ it might be more productive to ask; ‘how can political parties become organisations that offer local members fun, personal growth and social impact?’. The answer, of course, is that they would have to change out of all recognition.

A private corporation I recently addressed were also thinking in broad terms about how to become more creative and entrepreneurial. But the only method they seemed to employ was top down exhortation. A key question was; ‘how can we persuade our consultants to use their relationships not only to focus on their areas of expertise but to open up a wider offer to their clients?’ I suggested a focus on core human motivations could be a fruitful starting point.

There are three reason the consultants might go the extra mile; because they understand and appreciate this is part of the organisation’s strategy (hierarchical motivation), because they believe in their company and colleagues and the value they can bring to clients (solidaristic motivation) and because there is recognition and reward for those who take initiative (individualist motivation).

Whilst companies might conventionally order people to change or offer financial incentives, the trick is to tap into all three human motivation systems while not letting one crowd out the others. If incentives are too individualistic people may end up gaming or exploiting the system, if the encouragement is too hierarchical personal buy-in and creativity may erode, if the motivation is only solidaristic people may do what they think is right or good for their team but not necessarily in a way compatible with the needs of the whole organisation.

If we start our exploration of organisational change with a balanced and evidence-based model of motivation (albeit one that becomes more complex the closer we look at it) we can develop a richer, and often much more radical, account of how the organisation has to change to foster the behaviours it wants. Jos de Blok created the amazing Buurtzorg organisation in part because he could see a narrow focus on hierarchical and individualistic motivation had made care giving and care receiving joyless.

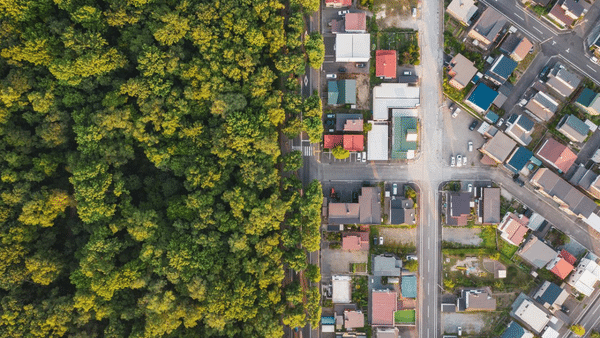

Similarly, as I have argued in other recent posts, we need to dismantle the high barriers to public sector collaboration by thinking in human terms first and structural terms second. I realise that much of this may seem blindingly obvious, but behind it lies a simple principle derived from the RSA’s Power to Create way of thinking. Let’s start all our conversations about organisational change with the question; how can we enable people to most fully express their creative potential?

Related articles

-

Design for Life: six perspectives towards a life-centric mindset

Joanna Choukeir Roberta Iley

Joanna Choukeir and Roberta Iley present the six Design for Life perspectives that define the life-centric approach to our mission-led work.

-

Inventing meaning and purpose: a politics award for our times

Ruth Hannan

Ruth Hannah is inspiring you to submit your creative and courageous political project to the Innovation in Politics Awards 2022.

-

Open call: Creative collaboration and collective imagination research

Hannah Webster Ella Firebrace

Learn more about the UNBOXED: Collective Futures open call; inviting you to submit what you are doing to help shape better futures for people and planet.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Your analysis is spot on. For a balanced and evidence-based model of motivation it's interesting to look at the Human Givens model proposed by Joe Griffin and Ivan Tyrrell (see www.hgi.org). While this has mainly been used within therapy and counselling as a powerful and transformational model of individual wellbeing, it is equally applicable at the level of social and business organisations and even states. Based on an account of innate 'givens' - emotionally-motivated human needs, and inbuilt or learned human resources for meeting those needs - it has been applied in settings as varied as Gaelic football team training, local government management and the Middle East peace process. As a retired sixth-form college English and Philosophy teacher and now an HG-trained counsellor, I'm biased - but my bias is grounded in growing evidence that the model works. Worth a look.