This is the third in a series of blog posts – part of the RSA’s Living Change campaign - which seeks to offer a unified framework for understanding human motivation, organisational change, policymaking and social progress. In this post I explore the modes of coordination that I introduced in my last post (hierarchy, solidarity, individualism and fatalism) in the context of organisational culture and change.

As Yuval Noah Harari has argued, it is the social sophistication of humans that most marks us out as a species. Put one gorilla on a large desert island with one human and it will likely be the gorilla who survives longest. Start with 50 of each and give the humans time to develop a plan and they will become the masters. Why? Because humans are better at coordinating their actions in complex ways. Indeed, the ‘social brain hypothesis’ argues that our brains evolved to enable us to form the large groups necessary for humans, as a quite physically limited species, to survive.

Gorillas on desert islands may seem far-fetched, but the range and sophistication of human approaches to coordination can be seen in more routine settings. I have more than 25 years’ experience as an organisational leader in contexts ranging from a tiny research institute in the English Midlands to the RSA. Across those decades I have had innumerable conversations about how the organisation I run could be better and I have sat in on meetings in many other organisations. I have learnt to recognise some recurrent narratives. Each time they are expressed differently. Sometimes they are mashed together. But listening carefully I can almost hum along.

The first story is about leadership, and as the boss it is probably the one I am most inclined to support. It also tends to be the assumption of the various Boards to which I have reported. The argument might be that the organisation has too many competing priorities and an unclear strategy. The solution proposed will be a process of organisational change based on a structured plan. It could require calling on the services of expert consultants or the recruitment of new managers. When this view is challenged, its advocates may grudgingly admit that previous initiatives of this kind have come and gone without lasting effect. But the underlying assumption is that change not only does but should come from the top down. After all, senior managers are paid to lead.

Because hierarchical principles run deep, this may be as far as the debate goes. But often, especially when the conversation involves a wider group of staff, another view emerges. The reference point here is the collective. This perspective may start with people’s feelings. Perhaps it is articulated by someone who prides themselves on spending a lot of time on the office floor and socialising with colleagues outside work. They want to share some worrying signals: staff are demoralised and feel the organisation isn’t living up to its stated values; colleagues are resentful of excessive disparities in pay and power and they want the organisation to be a more supportive and united team. It can be a fine speech; the one most likely to illicit murmurs of support or maybe even a round of applause. Because it has the power of moral suasion, it often goes unchallenged. It is only later that other managers might quietly express their scepticism. They point out that the organisation exists to be successful and provide a service, not just to make employees happy, or they painfully recall previous exercises in staff engagement, which became very inward-looking and generated unrealistic expectations.

The kind of people who are most sceptical about this solidaristic perspective are those inclined to be more individualistic. They think the focus on strategy over-complicates things while talk of values is vacuous and irrelevant. For them the solution to most problems is to liberate talented and creative people, maximising the scope for autonomy. As the familiar carrot and stick argument goes, the organisation should reward people for skill, hard work and achievement and be tough on them if they fail to meet expectations. In a commercial context this can sound brutal, but there is simplicity in this approach. Everyone gets it. Under pressure, the individualist might acknowledge the potentially divisive consequences of their approach, the danger that incentive systems encourage better gaming rather than better performance. But in the end, he (and, generally, it is he) argues that the added dynamism of autonomy and competition outweigh the potential dangers.

In these meetings the challenge is not just to reconcile the differences it is also to make sure everyone participates. I might notice someone zoning out entirely. I suspect they will go back to their partners or friends in the evening and report another waste of time “As we went through all the pros and cons” they might say, “I didn’t have the heart to remind them; we’ve done this all before. It never really changes anything.”

It is easy to condemn this apparent cynicism but fatalism is not without justification. As a chief executive I would judge two steps forward one step back as a pretty good success rate for organisational change programmes. In fact, an estimated 70% of such change strategies fail. Simple, incentive-based systems persist, but the evidence for policies like performance related pay is patchy at best while such systems routinely generate perverse behaviours. While there is evidence to suggest that a solidaristic strategy of staff engagement is more strongly linked to performance, attempts at full employee democracy rarely survive for long, especially when organisations grow large or face crises. Ultimately, despite a library of new books emerging every year on how to lead or to drive change in organisations, almost anyone who works for one can regale you with its many dysfunctions.

In my last post I described the big similarities and smaller differences between my view of human motivation (strongly influenced by the work of anthropologist Mary Douglas and her followers) and the very influential self-determination theory of Edward Deci and Richard Ryan. Intriguingly, it turns out that one of the most widely cited and applied frameworks in organisational theory has similar echoes.

The Competing Values Framework was developed by Professors Kim Cameron and Robert E Quinn, both based at the University of Michigan. The tools for assessing organisational values and developing change strategies, which Cameron and Quinn popularised in their best-selling book Diagnosing and Changing Organisational Culture, has been used in thousands of organisations and is the mainstay of many business consultants.

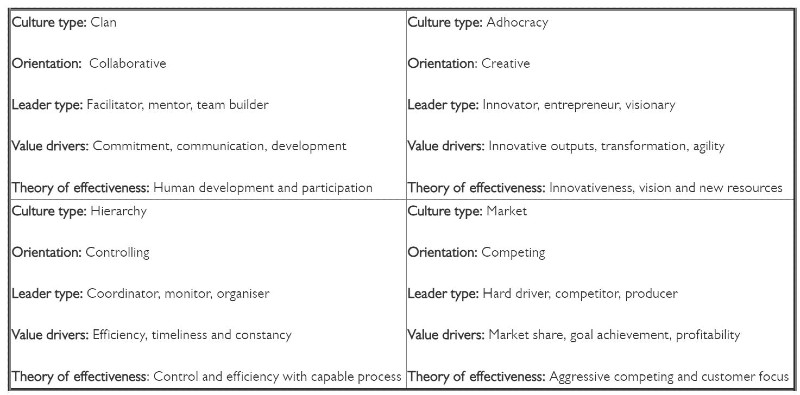

Cameron and Quinn identified four cultural types in business organisations: ‘clans’ in which the core principle is collaboration; ‘hierarchies’ in which control is paramount; ‘markets’ in which competition is king; and what they termed ‘adhocracies’ in which creativity is the most prized. In comparison to my own preferred categorisation, hierarchy, solidarity (‘clan’) and markets (individualism) map on pretty closely. Adhocracy is a hybrid category and one which Cameron and Quinn say is most characteristic of early stage businesses while, again, fatalism, is absent.

As well as being strongly based on empirical research and being illustrated through a range of case studies, the Competing Values Framework has a number of strengths.

First, it is dynamic, describing change and, to an extent, conflict. Cameron and Quinn analyse the way cultures evolve and cycle in business. Typically, start-ups begin life as adhocracies focussed around the creative idea of the founder. As they grow, they become close-knit clans of people who have strong sense of shared identity, purpose and destiny. Then if the business grows further it tends to become more hierarchical as the need for systems and control becomes unavoidable. Finally, for the business to survive long term it has to sustain or grow market share and profitability, something which leads to an overriding focus on competitiveness.

For example, Cameron and Quinn argue that tech giant Apple went on this kind of journey. It started with the adhocracy of the highly creative start up stage before evolving into an organisation built around the clannish band of Macintosh ‘pirates’ who developed the iconic home computer. The success and growth of the company then led to the hierarchical need to establish control and systems, exemplified in the appointment of John Scully from PepsiCo. The clash between hierarchy and clan led to conflict and the departure of Steve Jobs. Finally, in order to become one of the richest corporations the world has ever known, Apple has had to focus ruthlessly on staying ahead of the competition and sustaining its impressive profit margins.

The term ‘competing values’ suggest a recognition of conflict between cultural types. In fact, perhaps because Cameron and Quinn, like most business writers, are focussed on solutions, they underplay the inherent conflict between worldviews and the methods that come with them. But their research surfaces what they describe as a paradox. On the one hand, Cameron and Quinn argue that cultures work best when they align; when policies and practices conform with predominant norms and assumptions. On the other, they also find that the most effective leaders are those who demonstrate a capacity to work with all four of the cultural value sets. The fact that they sometimes present the cultures as stages on a journey adds to the confusion.

My own experience and perspective suggest different conclusions. Each set of values and practices (Cameron and Quinn’s competing values, my ‘forms of coordination’) reflect deep seated and inherent human motivations. All will be present as dominant narratives or subversive critiques in all social contexts. The issue for organisational success is whether (using my terms) each ‘form of coordination’ is positively articulated and, relatedly, whether the forms are held in some kind of balance. However, positivity and balance are hard to achieve and sustain for two reasons. First because each form is underpinned by values that are not only different to the others but to some extent gain their power and legitimacy from this opposition. For example, the case for a more individualistic or solidaristic approach almost always contains an implicit critique of hierarchical control. Second, because any significant change in the context in which an organisation operates will tend to disturb an equilibrium. Covid-19 has, of course, been a classic example of an external shock, leading among other things to major challenges to conventional forms of leadership, a stronger emphasis on aspects of solidarity (something deepened by the anti-racist movement) and, for many, a reappraisal of their individual priorities. These are ideas I will explore a lot more in later posts.

A second strength, displayed in the table below, is that Cameron and Quinn describe cultures in terms of a range of characteristics. This helps get a feel for how these cultures are manifested. Furthermore, the cultural value sets lead to contrasting perspectives on the same issue, for example, approaches to quality management or human resources.

In the same way, I have over the years been able to apply my own, similar, categories to a range of different issues. Once, for example, I gave a speech at a conference organised by a charity that promotes greater corporate transparency. The challenge was to engage a mixed audience of executives and experts some of whom seemed decidedly lukewarm. The charity leader had a background in encouraging corporate responsibility, so he was inclined to make the case in the solidaristic terms of values and ethics. Such an argument might seem too idealistic to senior executives, so I developed a hierarchical angle suggesting transparency can help leaders explain the difficult choices they face and the strategy they have chosen. To engage those thinking individualistically, I sold openness as a way of empowering people with knowledge and making their performance more visible. I even had a message for those with a fatalistic mindset, pointing out that when, inevitably, bad things happen, greater transparency might help us see them coming. Wherever a group of any size is gathered the four perspectives will likely be present; failing to make a case that appeals to each may mean some people have stopped listening.

In the same way, I have over the years been able to apply my own, similar, categories to a range of different issues. Once, for example, I gave a speech at a conference organised by a charity that promotes greater corporate transparency. The challenge was to engage a mixed audience of executives and experts some of whom seemed decidedly lukewarm. The charity leader had a background in encouraging corporate responsibility, so he was inclined to make the case in the solidaristic terms of values and ethics. Such an argument might seem too idealistic to senior executives, so I developed a hierarchical angle suggesting transparency can help leaders explain the difficult choices they face and the strategy they have chosen. To engage those thinking individualistically, I sold openness as a way of empowering people with knowledge and making their performance more visible. I even had a message for those with a fatalistic mindset, pointing out that when, inevitably, bad things happen, greater transparency might help us see them coming. Wherever a group of any size is gathered the four perspectives will likely be present; failing to make a case that appeals to each may mean some people have stopped listening.

Self-determination theory (featured in the last post) is well known to psychologists while the competing values framework is widely used in business studies and organisational development. But what if we looked across disciplines to identify how similar ideas can be seen as evolved instincts, individual motivations, organisational cultures, policy instruments and ideological assumptions?

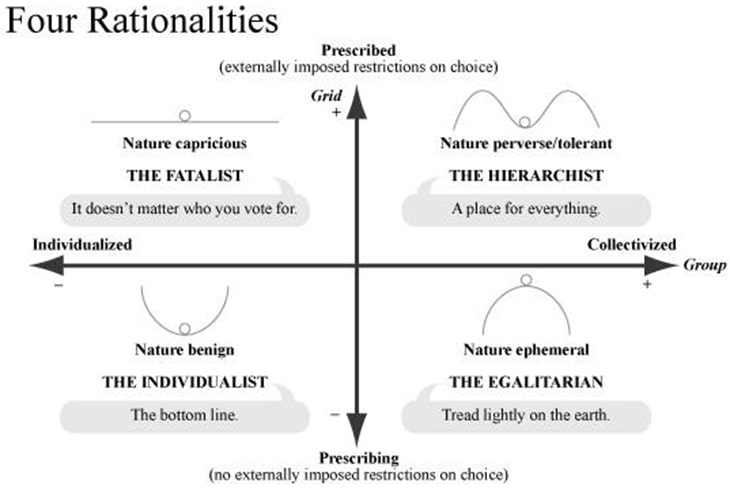

In the diagram below, from the work of one of the leading followers of Mary Douglas, Michael Thompson, each ‘rationality’ arises from and reinforces a view of nature. In the diagram the natural world is portrayed as ball on the plane. The individualist sees nature as benign in that however much we play around with it, it will return to a steady equilibrium. The egalitarian (Thompson’s name for what I call solidaristic) perspective is the reverse, seeing nature as very fragile and in need of careful preservation. The hierarchical perspective lies between, emphasising that with wise stewardship nature can be managed from one state to another. While for the fatalist the way nature behaves is unpredictable and uncontrollable.

We can see this pattern playing out in debates over climate change. Individualists may recognise that human activity causes problems but argue that history shows we can also solve them through market incentives and technological invention. Conversely, the solidaristic perspective tends to see the natural world as fragile and environmental degradation, change can only come about through a fundamental shift towards values of justice and responsibility. The hierarchical perspective is confident the looming crisis can be managed but only if we draw on the evidence and apply and obey the right expert-made rules. Finally, the fatalistic view is either that the science of climate change is a con or, if it’s true, that we may well be doomed.

We can see this pattern playing out in debates over climate change. Individualists may recognise that human activity causes problems but argue that history shows we can also solve them through market incentives and technological invention. Conversely, the solidaristic perspective tends to see the natural world as fragile and environmental degradation, change can only come about through a fundamental shift towards values of justice and responsibility. The hierarchical perspective is confident the looming crisis can be managed but only if we draw on the evidence and apply and obey the right expert-made rules. Finally, the fatalistic view is either that the science of climate change is a con or, if it’s true, that we may well be doomed.

So far, I have described a striking congruence between a number of theories about human personality, motivation, organisational culture and world view, as well as identifying some of the noteworthy differences between these theories. In my next post I will show how these categories appear again when we look at policy and politics.

The RSA has been at the forefront of societal change for over 250 years – our proven Living Change Approach, and global network of 30,000 problem-solvers enables us to unite people and ideas to understand the challenges of our time and realise lasting change.

Make change happen. Find out more about our approach. #RSAchange

Related articles

-

Young at heart

Journal

Jonathan Prosser

Becoming a nation with children at its centre in 10 courageous steps.

-

Open RSA knowledge standards

Blog

Alessandra Tombazzi Tom Kenyon

After investigating ‘knowledge commons’, we're introducing our open RSA standards and what they mean for our practice, products and processes.

-

Worlds apart

Comment

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.