As anyone who follows current policy debates will know, public policy has become increasingly preoccupied with the terms of exchange between citizens and the state, service users and public services. Labour, the Lib Dems and the Conservatives say they want to strengthen the bonds of civil society. All are talking about the importance of voluntary activity, ‘co-production’ of public services, civic participation, and what Matthew Taylor calls ‘pro-social behaviour’. It is a credit to the RSA that it is placed at the centre of this debate – and indeed often leads it.

One of the trademarks of work going on at RSA is an imaginative endeavour to draw on new findings from a range of academic disciplines – neuroscience, behavioural economics and social psychology - to improve our understanding of how we might forge a more constructive account of the terms of exchange between citizens and the state. But I want to suggest that, as well as making use of the latest ‘scientific’ thinking, we need better to draw on a long existing tradition of political thought – civic republicanism - which has always been centrally concerned with these relationships. We need to keep an eye on the rear view mirror.

We’ve seen growing interest among historians and political philosophers over the last generation in this civic republican or ‘neo-Roman’ tradition. This revival is associated with two names above all, the historian and philosopher Quentin Skinner and the political philosopher Philip Pettit.

Skinner in particular, has done much to recover the history of this tradition, and anyone interested in it should turn to his writings – notably Liberty before Liberalism. It is enough to say here that it begins with Roman defenders of republican constitutional rule, like Cicero and Livy, and is revived in the medieval and Renaissance Italian city states, above all by Machiavelli. It is then sustained and developed by defenders of the Commonwealth at the time of the English Civil wars, including Milton and Harrington in the 17th century, and by a broad current of 18th century thinkers, including Bolingbroke, Hume, Rousseau, Montesquieu, and defenders of the American revolution, like Hamilton and Madison. Republican thinking continued to be influential in the 19th century, informing, for instance, de Tocqueville’s analysis of the perils and possibilities of modern democracy and Mill’s brand of radical liberalism.

Contemporary civic republicans are not attempting to revive a moribund tradition but sustain one

What I want to do in the remainder of this post is sketch out - excessively briefly - some of its core ideas and values, and why these seem to me so potentially rich.

If there is one concern at the heart of civic republican thinking, it is with citizenship and how to win and sustain it. But citizenship plays a fairly complicated role in civic republican thinking. Civic republicans valued it because, as they saw it, only citizens were, by definition, free, but also because freedom could not be sustained without active citizens.

Let’s take each of these claims in turn. The idea that you can’t be free unless you are a citizen challenges a common liberal assumption, going back to Thomas Hobbes in the 17th century, that you are free in so far as no-one intervenes in your choices. Civic republicans, however, argue that this ‘freedom as non-interference’ is inadequate in at least one crucial respect. It implies that a person, even a slave, subject to someone else, is free in so far as that person does not interfere with them. Civic republicans claim, by contrast, that we can never be free as long as we are subject to someone’s will – as long as someone has mastery over us. That a master is kind or absent might make the subject’s freedom more palatable, but the subject remains dominated and so unfree. The only way of achieving real freedom, as least for a group of people at a time, is through instituting some form of constitutional rule that respects people’s fundamental interests or rights. Hence the inseparable connection between freedom on the one hand, and citizenship and republican constitutional rule on the other. (I am talking about republicanism in the broadest sense here. Some republicans, like Montesquieu, argued that republican principles could be realised under a constitutional monarchy).

At the same time – and here we come to the second claim – republicans also argue that constitutional rule needs active citizens to sustain it. Some of the later civic republicans, like Mill, recognised that constitutional rule was not entirely dependent on citizens to guarantee freedom – ‘professional’ judges, law-makers, journalists, etc could help make power accountable. But they all argued that a high degree of civic participation – through voting, holding public office, undertaking military or civic service - was an essential precondition of non-domination.

It should be clear now why this tradition connects to debates about relations between citizen and state, service user and public services.

But why revivify an idea that is over 2000 years old? And how can this tradition possibly hope to rival the fresh insights into human and social wellbeing offered by recent developments in social capital thinking, social psychology and neuroscience.izen, State, Civic republicanism, Quentin Skinner, Philip Petts, David Marquand

Well, first, civic republicanism is all around us. It has a purchase on us. In his lively history Britain Since 1918: The Strange Career of British Democracy, David Marquand identifies ‘democratic republicanism’ as one of the four traditions that have shaped and continue to shape British political life. (The other three being whig imperialism, democratic collectivism, and tory nationalism). From this point of view, contemporary civic republicans, like Marquand himself, are not attempting to revive a moribund tradition but sustain one. If we want more active citizenship and there is a tradition of it, it makes sense to work with it.

At the same time, I would contend that, as resonant as this tradition is, it remains hugely under-developed. Much of the recent revival of interest in civic republican thinking has been very abstract or philosophical in character. There has been, to my mind, strangely little attempt to look at either the institutional or cultural history of civic republicanism. Or to explore its connections to contemporary policy debates. Yet it seems clear to me, that, to take just a few examples, civic republicanism has profound things to say not only about the importance of constitutional rule, but about the importance of economic equality to citizenship, and the pleasures of civic life.

Of course no tradition is going to ‘deliver’ answers to the political and policy challenges we face. But there have to be huge gains in paying more attention to an extraordinarily rich and still resonant tradition centred on some of the most pressing and difficult problems that we face.

Ben Rogers is an associate fellow of ippr and a contributing editor of Prospect magazine. He has spent the last two years as a civil servant, working on social capital, civic engagement, planning and design policy.

Related articles

-

Worlds apart

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

-

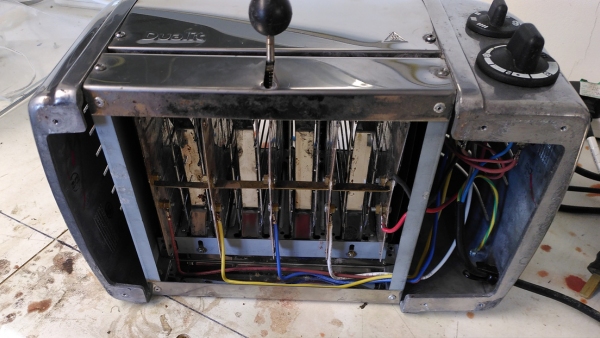

Why aren't consumer durables durable?

Moray MacPhail

A tale of two toasters demonstrates the trade-offs that need to be considered when we're thinking about the long-term costs of how and what we consume.

-

You talked, we listened

Mike Thatcher

The RSA responds to feedback on the Journal from over 2,000 Fellows who completed a recent reader survey.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

A very interesting post. I think that it is the underlying assumption to civic republicanism, namely that active citizenship is vital, that we most need to rediscover. As Steve points out in his comment, the high levels of voter disengagement is impacting upon every aspect of our democracy. The problem is, however, that there is a perception that this is not considered a problem by the political world. Instead of challenging the apathy and seeking to find new ways of engagement, it can seem that there is an acceptance that politics will trundle along quite happy without the participation of the public.

We need to re-emphasise the fact that civic participation is about public service and that serving as an elected representative is the greatest honour that can be accorded by our fellow citizens - not an easy task when we have MPs claiming immuity from prosecution!

Certainly debate is required.

I'd be interested to hear you talk about how high levels of voter disengagement and apathy as well as shockingly low trust in politicians affects civic republicanism. It's certainly interesting from a theoretical perspective but I'm wary if civic republicanism can flourish in todays political climate, especially from the perspective of the voters/citizens.