The problem with prisons is Immanuel Kant. Increasing adherence to Kant’s principles by law professors, judges and legislators has driven up prison populations in both the US and the UK. Kant’s principles do not incorporate the empirically observed consequences of imprisonment; rather, they scorn such facts in favour of consistency of method. The result is that too many people are not in prison who should be, and far too many people are in prison who should not be.

The people who should be in prison, according to Kant’s contemporary, Cesare Beccaria, are those whose imprisonment is necessary to prevent crime. The kinds of people who should not be in prison, in Beccaria’s Utilitarianism, are those for whom imprisonment does not prevent crime, and may even increase it. But how can we tell the difference?

Last year, the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society (Series A) published an article in which Richard Berk and I showed how we can forecast which offenders are most likely to commit murder or attempted murder. Our forecasting method is not perfect, but it is far better than the implicit forecasts many judges make solely on a subjective assessment of the offender’s prior record. Our approach is like tomorrow’s weather forecast. We can distinguish where it is most likely to rain from where it is not, and get it right most of the time. Like a weather forecast, our method employs tens of thousands of prior cases to develop a forecasting formula, and then tests the formula on tens of thousands of different cases.

If we do not know whether having 86,000 people in prison deters more first offenders than having 40,000, why should we spend the money?

Beccaria would say that people who are highly likely to commit murder, sadly, should be locked up far longer than those who are not, simply in order to protect society. He would also say that no one should be locked up for a short sentence if they will come out to commit more crimes than they would have done had they never been locked up. A large study of Dutch prisoners published last year by Daniel Nagin and his colleagues in the Journal of Quantitative Criminology showed that, on average, offenders under the age of 25 will triple their offending rate after a short prison sentence - compared to offenders with similar records and present crimes who were not sentenced to prison.

In a larger review of the evidence on imprisonment last year for Crime and Justice, Nagin and two other colleagues concluded that there is no indication that prison reduces crime by those who are imprisoned, and some evidence that prison causes the imprisoned to commit more crime. Like the Dutch study, that conclusion factored in the time behind bars. Among those put in prison, it causes enough additional crime to wipe out the crime-free period behind bars.

The unanswered question is how much crime prison prevents among people who have never been there. More precisely, we do not know whether having 86,000 people in prison deters more first offenders than having 40,000 or 20,000. But if we don’t know, why should we spend the money? Such spending seems even more reckless if we can be pretty sure that those sent to prison will only commit more crime as a result.

If prison were a pharmaceutical, judges would not be allowed to use it for sentencing until it had been carefully tested for safety and effectiveness. The method of testing would have to be a randomized controlled trial, the highest possible level on the five-point Scientific Methods Scale my colleagues and I developed for the US Congress in 1997. As Rachel O’Brien points out in The Learning Prison, this kind of evidence could be used to limit all government spending on crime to strategies that are cost-effective—including prison itself. Such evidence could also be required for early release from prison, for rehabilitation programmes, and for every kind of sentence served in the community, from electronic tagging to community service in bright orange jackets.

Yet a major exception to such testing must be the most dangerous offenders. For them, the forecasting evidence outweighs the question of sentencing effectiveness. We cannot risk a test of prison’s effect on future crime after release on people who should perhaps never be released, or not released for many decades. There is far too little transparency in the UK, for example, about second murders by previously convicted murderers who were released after a prison sentence. The questions about Professor Amy Bishop’s killing of her own brother 24 years before she reportedly killed three of her colleagues, as a further example, are multiplied whenever a murderer is released after completing a sentence. Mental illness or other factors may make some people justly deserve a lifetime loss of liberty, at least by Beccaria’s principle of prevention.

Law professors object to statistical forecasting because (1) it contains error and (2) it punishes people for what they might do rather than what they have already done. Beccaria would argue, with Churchill, that a system need not be perfect to be the best one available. Our current system encourages the over-use of prison to avoid criticism of judges or the government, “just in case” the offender commits a horrible crime. The result is a massive waste of money and lives. If the use of statistical forecasting in sentencing decisions could cut prison populations in half, the total harm from prison would be far less than that caused by Kant’s principles.

Lawrence W Sherman FRSA is Wolfson Professor of Criminology and Fellow of Darwin College at the University of Cambridge

To correct this error:

- Ensure that you have a valid license file for the site configuration.

- Store the license file in the application directory.

Related articles

-

Worlds apart

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

-

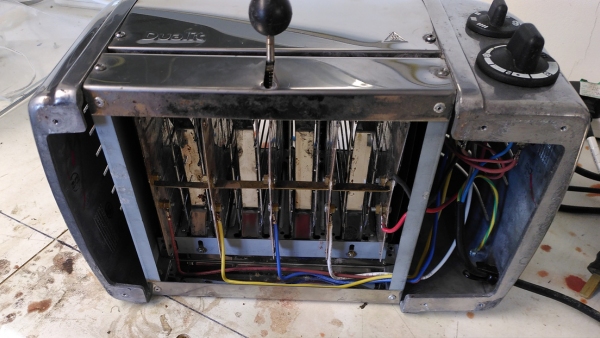

Why aren't consumer durables durable?

Moray MacPhail

A tale of two toasters demonstrates the trade-offs that need to be considered when we're thinking about the long-term costs of how and what we consume.

-

You talked, we listened

Mike Thatcher

The RSA responds to feedback on the Journal from over 2,000 Fellows who completed a recent reader survey.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

It is tempting to blame Kant for the huge over use of imprisonment in the UK. However, just because he gave penology a few key concepts does not excuse the British criminal justice system from its responsibilites to seek to ensure the protection of the public whilst also trying to reduce reoffending. If we know - and we do - that the use of UK imprisonment fails to reduce reoffending whilst locking up large numbers of mentally ill and/or socially deprived children and adults, I think it would be a bit of a cheek for us to try to excuse ourselves by saying that Kant, Beccaria or any of these other long dead philosophers gave us permission. I am sure that Jack Straw would not hide behind such a sad excuse!

Crime has unfortunately become a lynchpin of political debate, which means that scientific study and policy has fallen to the wayside in the attempt to sway the electorate one way or the other.

The problem that any kind of meaningful analysis and study of prisons faces is the vast public perception that they exist purely for punishment. It's very easy to exploit people with sound bytes like "Prisoners cost XYZ dollars per day", or "wow, prisoners have access to the internet? that's not fair"

On the other hand, protecting prisoners rights can get a little out of hand. After all, convicts are hopefully in prison for a legitimate reason and part of their imprisonment is to protect society. Especially in the case of violent felons.

It's a hard balance to find even without the politicization of the issue.

It's stating the obvious but the more fundamental question is, why do areas like prisons and mental health attract emotive policy making rather than that based on evidence?

For me the most powerful point made by The Learning Prison report was that of the openness needed to change that kind of culture. It would have been good if the report had been a little more clear on how that openness could be achieved though... but that's clearly a way forward to dragging this out of being an emotional social topic.

The colossal gap in evidence around criminal justice issues, especially around the use of prison as a deterrent to crime, is enormously problematic for the very reasons you discuss above. There is a fundamental lack of hope ingrained in the approach - where is the recognition of people’s ability to change given the right context and support?

I'm also troubled by the lack of definition around mental illness. Should I read this to mean that everyone with a mental illness should be imprisoned because they’re more likely to commit crime?

We all know that those individuals suffering from multiple deprivations - social, cultural, education, financial – are more likely to commit crime so rather than giving them a prison sentence, just in case, we need to take responsibility for addressing these issues first.

I look forward to reading the research mentioned above.