It is nearly a decade ago since a brief conversation I had with a prominent member of the New Labour cabinet, who asked me what book I was writing next. I told him I was questioning the idea of targets. These were the days before opposition to targets had become relatively fashionable, and he was enjoyably astonished. “But what else can we do?” he asked.

Ten years later, targets are out, along with much of the detritus of what used to be called the New Public Management. Measuring by ‘outcomes’ – measuring the effects of the activity rather than the activity itself – is in.

Quite right too, but we are not yet shot of targets by any means. Partly because, as we will see, the coalition’s other ambition (‘payment by results’) will take us right back there. And partly because the obsession with measurement is deep within the soul of Whitehall, not to mention McKinseys and all their other well-paid advisors. They itch to measure everything.

So let’s just get back down to basics for a moment. Measuring things has gripped the zeitgeist by the throat because numbers seem to provide a hard-headed anchor of certainty in a relative world.

The problem isn’t with the numbers themselves, it is with the definitions at the other end. Those tough-minded mandarins who demand robust numbers forget that, chained to the numbers are some very un-robust, rather fluffy and subjective words, which can be endlessly manipulated.

Hence what has become known as Goodhart’s Law (after former Bank of England director Charles Goodhart) which says that: any measure used to control people – and all targets are that – are bound to be inaccurate. No matter how inefficient an organisation is, their staff and managers can always manipulate the definitions so that their target numbers look better.

No patients on trolleys? Let’s get in posh trolleys and define them as ‘mobile beds’. This is only one real example. There are examples of rules employed in back offices to close applications if they threatened to break time limits. There were as many examples as there are targets.

So here is the difficulty with the flagship coalition policy of payment by results. You can pay contractors for what they do, even for an immediate treatment (which is what the NHS, quite inaccurately, calls ‘payment by the results’). You can even make an attempt to measure the long-term effects of actions (outcomes). What you can’t do, without running foul of Goodhart’s Law, is to stick the two together.

Who achieved these outcomes precisely? Where is the causality? When is the cut off point when the outcome is defined as permanent? Those are problems even before we start to look at how the definitions of success get manipulated, as they inevitably will be.

Never mind Goodhart’s Law, which is about using numbers for control. Here is what I humbly submit as Boyle’s Law: When you use numbers as the basis for payment, they become irrelevant to the broader objectives of the service.

This will, in short, hollow out and subvert the service that is being paid for, just as bonuses – also a kind of payment by results – did for banking. It will shift the energy and focus – not to encouraging services which can genuinely prevent – but to selecting the clients who can fulfil the definitions of the outcome with the minimum effort. Worse, it means excluding clients who are difficult or even just difficult to define.

In practice, it will mean a whole raft of new definitions, rules, audits and procedures to keep the services focuses, and – hey presto! – we are back with targets again.

That is how the Labour government managed to spend huge sums checking, auditing, re-defining and systematising their controls. Every time they did so, the rules became more complex, more expensive and less connected to reality, but those manipulating the target definitions still stayed one step ahead, as they always will.

The regulators found themselves prosecuting teachers and doctors for fiddling their target results. The next step will be the inevitable prosecution of charity workers and social enterprise managers for manipulating the data to speed up their long-awaited evidence-based payments. Because, this won’t just be fiddling with definitions to look good. It will be fraud.

The successes of the New Labour years (rough sleepers, for example) often happened when they dumped the targets and tackled the most difficult cases first. Payment by results encourages managers to do it the other way around. It encourages them to tackle the easiest cases first and to leave difficult cases for someone else.

None of this suggests we shouldn’t innovate in the way we commission public services. Quite the reverse, but we need to understand that ‘outcomes’ are extremely complex, because human problems are complex. Pretending they are simple and easily assignable and measurable leads to the difficulties.

Instead, we need to challenge providers to innovate. We need to ask organisations bidding for public service contracts how their services will also build community. We need to ask them to compete for contracts on the basis of how they will create supportive mutual networks and how they will prevent problems in the future. Every public service contract should include a commitment to create the kind of service that reduces future demand.

So yes, let’s measure outcomes, but let’s do it accurately and work with the complexity rather than pretending it isn’t there. That means the very last thing we should do is to muddle those measurements up with money. Remember Boyle’s Law.

David Boyle FRSA is a fellow of the New Economics Foundation and co-author of Eminent Corporations: The Rise and Fall of the Great British Brands.

Related articles

-

Worlds apart

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

-

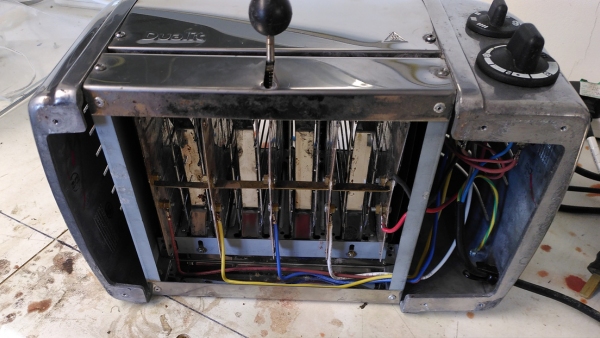

Why aren't consumer durables durable?

Moray MacPhail

A tale of two toasters demonstrates the trade-offs that need to be considered when we're thinking about the long-term costs of how and what we consume.

-

You talked, we listened

Mike Thatcher

The RSA responds to feedback on the Journal from over 2,000 Fellows who completed a recent reader survey.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

The majority of local authorities do not carry out effective commissioning focusing on outcomes and will struggle to provide an effective payment by results system. There is insufficient understanding or commitment - nationally and locally- on moving to proper outcomes focused commissioning linking children, families and communities together. Your summary is spot on. Right now cuts are being made on the basis on unit costs not need or effectiveness. Prevention and outcomes will struggle to get a proper hearing.

In the U.S. we've solved this issue by ignoring actual outcomes altogether.

I am surprised you have not mentioned the work of John Seddon and his Vanguard group http://bit.ly/Y9DI; his primary focus is on improving the response of service companies to customer demands, but he has been very active in the UK, especially at the local level, in trying to address this problem in government. You may want to see his recent book on the subject: "Systems Thinking in the Public Sector--the failure of the reform regime...and a manifesto for a better way."

Cheers

Agree. Agree. If only everyone can get past the headline...which is the subject of my latest post http://t.co/H7oYJli

"This is the problem of attention-span. To understand something—an essay, an argument, a proof of innocence—requires a certain amount of attention. But on many issues, the average, or even rational, amount of attention given to understand many of these correlations, and their defamatory implications, is almost always less than the amount of time required. The result is a systemic misunderstanding–at least if the story is reported in a context, or in a manner, that does not neutralize such misunderstanding. The listing and correlating of data hardly qualifies as such a context. Understanding how and why some stories will be understood, or not understood, provides the key to grasping what is wrong with the tyranny of transparency." – Larry Lessig via O’Reilly Radar

Couldn't agree more about process being devalued. I have often had it thrown at me as though it is a negative thing. Well I am really enjoying watching the current twists and turns and shenanigans over 'behaviour change' inside government, as they run after one new fashion after another over the last few years. The search for magic bullets and one size fits all just gets harder and more focused with more and more measurement of what we can measure. Actually the problem is that for sustainable development people keep forgetting that second word - development. If they had taken that to heart and had noted that government has always been in the process of behaviour change in one form or another their current behaviour patterns would not occur. Instead they would be reflecting on what they have learned so far, and instead of working harder or in a more focussed way be working out that this is a process of change - complex, multi-faceted, involving many people, motivations and interconnected issues. The process is to become literate in social change not just work harder on one behaviour as though it is a product.