Increased diversity in public sector provision should be welcomed argues Tom Levitt FRSA. Strong partnerships between the state, the private sector, social enterprises and charities can work to strengthen all players in meeting the needs of the nation.

Let us define public services as those provided for the benefit of the public: not necessarily provided only by the public sector. Whilst that sector has traditionally provided such statutory services there has always been voluntary provision by civil society as well. Increasingly sector boundaries have blurred as, through commissioning, more services are provided by the private (for-profit) sector and voluntarily provided services have been brought into the fold on an arm’s length or quasi-statutory footing.

The diversity of beasts in this jungle has grown: whereas once it was populated by three - ‘public bodies’, ‘charities’ and ‘private companies’ - today a whole lexicon exists: social enterprises, employee mutuals, consortia, business-charity partnerships, even ‘social businesses’ are between them seeking to provide the greatest variety of sustainable, impact-driven, beneficiary-led services.

Not only will this trend continue, it is also a good thing: provided certain caveats are met. It is good not just because it meets a benign policy objective, Big Society, but because it is the only way of extending the reach of services to those in most need in a financially sustainable way at a time of economic stress (i.e. the foreseeable future). There at least are five good reasons why this should be the case.

First, we have reached the limit of what the central state can provide. After 13 years of Labour government the number of people and communities that were socially excluded was far too high. Many communities do not feel in control of their local environments and too many individuals are alienated through poverty, disability or lack of opportunity or access to the formal economy.

This is not due to lack of government funding; Labour had its years of plenty. Nor is there a lack of political will. Rather our lack of success is due to an innate inability of central government to function well at the extremes of its influence. The emasculation of local government - seen by Whitehall as an alternative power base and therefore a threat rather than an opportunity - combined with personalisation and localisation, two concepts which command such consensus that they are at the heart of the Coalition government’s ethos, have made challenges to central government hegemony even stronger. Emasculation was wrong but personalisation and localism are right, popular and essential.

Second, service-providing charities need greater diversity of support. For 100 years charities have been largely dependent on individual and philanthropic giving. Such public services as they grew to provide were naturally complementary to or extensions of those of the state. Thus it was perfectly natural for the state to look to the voluntary sector when seeking to diversify, extend or deepen its capacity to serve. Indeed, the funding was seized upon with alacrity, to the extent that charities’ lack of historical need to protect themselves against funding ‘shock’ left them highly vulnerable in the new environment of austerity. In the good times they should have better prepared a broader funding base and reduced dependence on the taxpayer, a caution that applies both to the giants and the minnows who have taken the Queen’s shilling over the years.

This situation demands a new and imaginative role for single tier councils as commissioners, arbiters of standards, equity and fairness and friends of both beneficiaries and providers.

Third, the private sector is the nation’s biggest untapped pool of resources. Taxation is the traditional way of extracting cash from the private sector for public good. We have recently seen the legal lengths that some will go to in order to minimise this. As capital is now truly global, it is unlikely that taxation can wring a lot more blood out of this particular stone. However, private business is not just a cash cow; it contains employees and other resources. Just 3 per cent of UK employees undertake payroll giving, a tenth of the US figure. Just one UK employee in every 14 has been a community volunteer in their employer’s time whereas in America it is one in three. Skills, especially for growing capacity, are amongst the most powerful things that business can donate to the voluntary sector of the future if public services are to be delivered collaboratively and sustainably.

Fourth, demands are growing for business to be both reasonable and ethical. ‘Irresponsible’ sums up the behaviour that led to the 2008 banking crash. Today Barclays and Starbucks - amongst the biggest supporters of UK communities through their donations of assets and skills - must respect public belief that excellence in social responsibility is not an alternative to paying fair taxes but must accompany it. At the other end of the scale Unilever has switched to annual reporting to make its company more attuned to longer-term sustainability, while Serco has embarked upon genuine partnerships with charities on many fronts and investors generally are looking towards achieving social outcomes rather than purely financial returns. If we really are ‘all in this together’ then there are green shoots of responsibility if not in the wider economy.

Underlying these trends is the fact that is our fifth reason to believe that public services can change the face of responsible capitalism: there is a business case for good corporate citizenship.

In international conglomerates and corner shops, staid family businesses and pulsating e-commerce company engagement with local communities, perhaps through the medium of charity, is good news. Community involvement is the Siamese twin of employee engagement, itself a stimulus for greater worker satisfaction, loyalty and productivity. A good CSR policy, meaningful not superficial, can promote innovation, increase shareholder return and protect against market shock.

People in all three sectors and across the political spectrum recognise the power and potential behind these five truths. Many in business are ready to come on board the responsibility bus and accept that ‘stakeholder’ means more than ‘shareholder’. Big corporates like Marks & Spencer demonstrate that thoroughly ethical behaviour in community, environment and supply chain can be profitable whilst helping society meet the myriad challenges of the 21st century.

Traditional views of each sector fixed in its place helped us throughout the 20th century. They will hold us back in the globalised, interdependent world of the 21st.

Related articles

-

Worlds apart

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

-

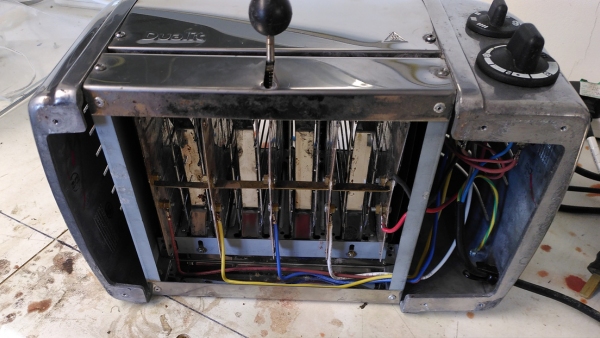

Why aren't consumer durables durable?

Moray MacPhail

A tale of two toasters demonstrates the trade-offs that need to be considered when we're thinking about the long-term costs of how and what we consume.

-

You talked, we listened

Mike Thatcher

The RSA responds to feedback on the Journal from over 2,000 Fellows who completed a recent reader survey.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Not to rain on the parade of the first person to comment, but I find this a mix of unsubstantiated ideology and wishful thinking. For example, there is no evidence -- or theory for that matter -- offered to support the contention that the state has reached the limits of what it can provide. The money argument is too narrowly focused and misses the broader trends that Labour tolerated and promoted, many of the resulting in greater socioeconomic inequality. Furthermore the argument seems to presume that big is bad . . . in term so of government. Is it not also bad in terms of corporations? Second, why is it preferable to funnel money to/through charities rather than government? Many charities remain in the hands of churches and limit or tailor their services based on belief rather than more objective standards. A recent example comes from Germany where the state has depended heavily on the Catholic church to provide social and health services -- on which it imposes restrictions based on its doctrines rather than need (www.spiegel.de/international/g.... One of the major problems with foundations and tax-deductible donations has been that it privatizes the allocation of resources for what should be public purposes. An example here would be the Gates Foundation that supports GMO crops despite a growing body of evidence of the problems with them. What kind of partnership is possible between public and private in this case? The problems with this piece goes on, but I will end with the most absurd contention, that businesses will somehow become more ethical! Google and Starbucks and Amazon actively (and brazenly) work to manipulate tax codes to increase their bottom line. Does the writer HONESTLY believe that these behaviours are simply reactions to a tax code and will not carry over to others? If so, could he offer some evidence please. The only evidence we do see suggests otherwise. Assuming that ethical practices CAN be good business, that is not to say businesses will recognize that. In the short term recent behaviour suggests they will continue to respond to the short-term bottom line, the ethics or consequences for society at large be damned. Furthermore, is it better to have a BP that funds charitable works, or one that acts responsibly to avoid disasters like that in the Gulf of Mexico? Please, give us less nice, upbeat prose and more well reasoned arguments with EVIDENCE.

Hear, Hear - Kudos and all similar congratulations on a thoughtful, thought-provoking and well said piece.