As spending cuts continue to impact on arts funding, the need for measuring impacts is more important than ever. William Wingate FRSA argues that there maybe an unlikely model from which to learn: transport.

Writing in the Journal in Spring 2011, John Knell argued that arts organisations need to change the way they justify their need for public funding, and suggests exploring the applicability of a “social return on investment” model. The Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport, Maria Miller, reinforced the message that arts funding needs an economic case in her recent speech. But the practicalities of creating and presenting the case consistently and persuasively are vitally important.

Having been involved both in the appraisal of transport projects and in making and assessing applications for arts funding, I wondered at the time if – unlikely though it might sound – there might not be something like a ready-made solution in the way in which transport projects are appraised in the UK. The creation of the joint Arts Council/RSA seminar project, which aims to develop a new political economy for the arts and culture, makes it timely to have a first stab at crystallising these thoughts.

Transport projects are often (although not always) Big Projects demanding Big Investment, and rightly require robust justification. The central plank of this has for a long time been Cost Benefit Analysis which sets benefits against costs to understand return on investment (often expressed as a benefit cost ratio, or BCR). However, the need to quantify benefits in monetary terms, which is not always possible, prompted the development of the New Approach to Transport Appraisal (NATA), set out in the 1998 Transport White Paper. The paper included two important innovations: first that NATA looks at a wider range of benefits, including some which may not be quantifiable, and second it developed a consistent format for presenting the results, the Appraisal Summary Table.

The methodology has undergone constant revision and refinement over the years, evolving into a substantial set of guidelines known WebTAG available to all on the Department for Transport website. There is too much detail even to summarise here, but the important thing to note is that the Appraisal Summary Table included effects that may not be quantifiable in monetary terms or even at all but which nonetheless count in the overall analysis (note also that a negative ‘score’ is always possible).

So for example, alongside economic effects such as those that impact business or tax revenues, it includes environmental effects such as heritage and biodiversity, and social impacts such as journey quality, access and affordability.

But why should this be of interest to the arts? The simple fact is that robust transport appraisal gets projects built. Even in these recessionary times, substantial amounts of money have been and continue to be committed to transport projects, especially rail projects. Appraisals may not always give the ‘right’ answer (what forecasts do?), but there are at least two reasons why they are trusted enough to form the basis of investment decisions.

First, consistent methodology and presentation makes it much for fundholders to evaluate, compare and prioritise different proposals. Secondly, the focus on a single appraisal framework has in turn focused research in the areas in the framework, making it more robust. For example, time savings for travellers are one of the most important benefits, leading to a substantial body of research into how these can be given a monetary value. Similarly focused research on, for example, audience benefits could be similarly beneficial.

Developing a consistent presentation of benefits from arts investment akin to the transport model is, in principle, a straightforward task of listing and categorising the benefits. In practise, it will take time and discussion to achieve a consensus, and the result will continue to evolve.

The bigger and more time-consuming task is to build the methodology. But as a starter for ten, consider that the transport appraisal framework includes a ‘hierarchy’ of benefits, which have analogues in the arts. These include financial benefits, which in the arts context are relatively straightforward: for example, the arts world has become adept at quantifying the VAT raised by arts activities. Non-financial but monetisable benefits may be the area needing most work, and would require marshalling existing research and carrying out more work to understand how, and by whom, arts projects are valued beyond the revenues they generate. Meanwhile, non-monetisable but quantifiable benefits can be measured through actual and potential audience sizes (for example, catchment area), whereas non-quantifiable but still tangible benefits might include environmental or reputational effects.

The development of a coherent ‘Arts Appraisal Framework’ is work in progress and these ideas need further development. However, the transport model provides a potential answer to convincing fundholders to fund the arts and an opportunity to learn from and adapt an existing successful mechanism, rather than reinventing the wheel.

Related articles

-

Worlds apart

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

-

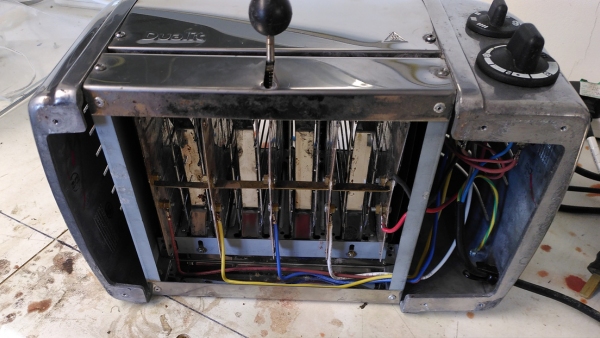

Why aren't consumer durables durable?

Moray MacPhail

A tale of two toasters demonstrates the trade-offs that need to be considered when we're thinking about the long-term costs of how and what we consume.

-

You talked, we listened

Mike Thatcher

The RSA responds to feedback on the Journal from over 2,000 Fellows who completed a recent reader survey.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Very thought provoking article and you might be interested to know that the (now abolished) RDA Yorkshire Forward - was in the processing of mapping out both the economic and other benefits of the applied Renaissance Methodology to the Renaissance Towns. There were 13 measures applied, both qualitative and quantitative which were intended to be measured over time (25 - 30 year span because it sometimes takes that long to see the full impact). These measures were compared against 'non-renaissance towns'. However, this initiative was terminated (as far as I know) at the point of abolition of the RDAs two years ago, however, the results that were already emerging were demonstrating how both the economic results tied strongly with the other less easily measurable results such as social, environmental, and cultural indicators.

The value of an emphasis on quality placemaking, combined with the 'town teams' - people being involved with the reshaping of their places, was proving to hold strong and positive outcomes.

However, to demonstrate this within a funding application with its reliance on empirical data alone would be misleading and short-sighted.

I wasn't intending to suggest that the transport framework would work unchanged for the arts, and you are quite right that simply replacing "transport" with "arts" in the framework would be largely meaningless (but if you want to do it, the link is http://goo.gl/bOCTY), nor was I trying to imply that art is only about economics (as per your tweet).

You are absolutely right about all the "non-measurable" (for want of a better word) attributes of art. Like it or not, though, the arts has been thrown the challenge of producing an economic justification of some sort, and I simply wanted to point to an example of a respected and established evaluation framework which might form a useful model. One of its strengths is the inclusion of non-measurable factors, meaning that even if they aren't measured they are at least acknowledged and articulated. One or two of them are not completely irrelevant in fact, for example Townscape and Heritage are both on the list.

The other lesson from the ever-expanding body of research is that it is possible to value and measure more than one might expect, albeit imperfectly.

This is an interesting idea but it is difficult to see how one can use such a framework to measure intrinsic satisfaction - meaningful intellectual stimulation, sense of wellbeing, emotional impacts such as enchantment,

passion, raising political awareness, human rights, excitement, intrigue –

basically the many things that art can engage us with as humans, whereas a transport system is, well, a transport system. Not everything in life is about logic, not everything is measurable.

A good test would be to take one of these frameworks and switch the words transport for art – where can I get a copy please? I doubt it would make much sense.

Maybe a New Approach to Transport Art Appraisal could financially justify arts existence, but as arts purpose goes far beyond economic efficiency and logistics it may be a meaningless exercise.

You are absolutely right, of course, that this is essentially an application of multi-criteria decision theory. The difference, however, is that in the transport appraisal framework, all the quantifications are absolute. The non-quantifiable variables tend to be scored on a "strongly positive" to "strongly negative" scale and function more as a prompt to ensure that the project isn't doing nasty things (or if it is that there will be costs associated with mitigation).

This means, as you rightly spotted, that the appraisals can stand on their own and are hopefully free of some the biases which come in traditional MCDT, where there is a risk that people will score the projects they like more highly regardless of merit. In reality, of course, they are used to compare competing projects, although the prioritisation will take affordability into account as well.

Interesting piece. It's not just the transport sector that has evolved a robust framework, but it's as good an example as any. I've used similar frameworks in both IT and business project approval. In both cases, we had to create a framework such that projects are assessed against the same set of variables as others of similar scale. Some small scale projects will never have an enterprise-wide benefit so will always 'score' badly if in competition with others with a more pervasive reach - in such cases we removed those categories and sought to compare like with like. However, this was because we were choosing which of a number of candidate projects would receive a share of limited funding. As a standalone assessment of valueyou wouldn't have the comparison bias to deal with.

If I'm reading your piece correctly, the key takeaway is that project-focussed commercially-driven industries have come to know how to do this kind of appraisal and would do it almost instinctively, whereas those with a more artistic focus don't necessarily have the commercially- or financially-focussed vocabulary with which to convince prospective investors that their project will give a big enough return on investment.

A good example of cross-sector best practice sharing.