The UK’s mainstream political parties agree that we need more homes and to cut carbon emissions. Stewart Fergusson FRSA argues that the ‘passive house’ approach, which is well developed in parts of Europe, provide one answer and that housing associations should lead the drive for innovation.

Building more homes is now a promise made by all key political parties. Given the UK’s woeful housing shortage, numbers matter; but the fear is that we will produce the same old product that is small, cheap to build and expensive to run. Energy prices are also in the spotlight; yet again the international scientific community has signalled man-made climate change. Given that 27% of the carbon emissions of the UK come from our homes, their energy performance needs to be addressed urgently.

Currently, most attention is on the Government’s Green Deal and Energy Company Obligation (ECO), designed to finance energy improvements to existing homes. But whilst we cannot ignore our legacy of housing that is expensive to heat, we need to be mindful of the adage, ‘turn off the tap, and then empty the bucket!’

The challenge to build low-carbon homes could easily slip down the agenda in the rush for numbers, with the debate regressing to why it is difficult and costly to do, rather than how it can be done. There are a number of reasons for this. The Government’s concern is not to burden the construction sector with new building regulations that might increase their costs, notwithstanding that the Latham and Egan reports on the construction industry identified significant opportunities to improve productivity. The risk is that politicians relax a little as ‘fracking’ means we can squeeze the earth like a wet sponge and get another fix of fossil fuels to keep the lights on and the gas boilers burning for another generation. Affordable housing providers will have to squeeze evermore units out of a declining grant pool.

An alternative is to adopt the mantra of ‘fabric first’: build homes that do not need much power to run them, and ensure what they do need can be provided by renewable technology. Parliament’s energy and climate change committee recently urged the Government to focus on producing homes that do not call on so much energy. Too much money, it warned, is spent on helping with bills rather than improving energy efficiency. This is an eminently reasonable proposition; but how do you make it happen?

The passive approach to construction is based on simple principles, reliable technology and is well tested particularly in northern Europe. It produces homes that require as little as 15 kilowatt hours of power per year to heat one square metre of floor space compared to 80 to 100 for most modern homes. Moreover, it is only marginally more expensive to produce a passive house. If we can build homes that do not need expensive and damaging fossil fuels to power them, why contemplate building anything else?

In part because this kind of innovation is new to the UK housing sector. An innovation is the creation of more effective products that are accepted by customers, markets, government and society. An innovation must address the question “What does this innovation have to reflect so that people who have to use it will want to use it and see in it their opportunity?” And here is the rub; suppliers of new homes may not see in it their opportunity. UK house building is a relatively innovation free zone compared to northern Europe: in the UK we have built less than 200 passive homes, while the Germans have built 20,000. Again, the risk is that with the focus on fracking and a modest adjustment to building regulations, our builders will settle back into their comfortable old ways; build homes as cheaply as possible, sell them and move on; let the buyer worry about running costs.

Houses are products of engineering. Those designing and building homes should adopt the approach of other engineering sectors. Imagine: houses designed to deliver virtually energy free heating performance, built in a factory where the haphazard quality control of the building site is replaced by the reliability and consistency of the production line. It happens occasionally, but it should be the norm. We should demand of our developers new homes that meet the passive house standard with this simple output measure of an annual heating footprint of no more than 15 kilowatt hours per square metre of floor space.

Some enlightened developers are now increasing their off-site production of new homes by investing heavily in house building factories, the only building method that can reliably deliver this type of low energy home. Still, only about one in four homes are produced by this method.

A few innovative developers and housing associations are also experimenting with passive house concepts. But most argue it is still too costly and few UK contractors embrace this as a norm. Perhaps they lack the inclination, the incentive, or the expertise to adopt such an approach, given the short-term pressures to deliver numbers and profits. But housing associations are also slow to adopt this standard; and they should be different. Housing associations have to manage what they build, and their customers are the ones who suffer most from fuel poverty and have to bear the brunt of new welfare policies. Lower heating costs could alleviate the increase in other housing costs. Cost in use, not cost to produce should be higher up the agenda.

Innovation comes down to leadership. As big clients of developers, housing associations should lead the way and be more assertive in their requirements for homes that are cheap to run. Leadership is less likely to come from a government who want more numbers at no extra cost and who are more susceptible to the pleas of developers and power companies than householders threatened by fuel poverty. Developers are unlikely to take the lead until they see a marketing gain in building passive housing at scale.

But will the necessary leadership come from housing associations? The gold standard of leadership in the movement is now increasingly characterised by the mindset and values of the merchant, the money manager and the developer. It would be an interesting exercise to analyse the composition of the boards and senior management of large housing associations. I suspect it would show a strong trend of leadership becoming increasingly dominated by able accountants and traditional UK developers. Do they have the imagination to rise above their role as numbers people and executors of the prevailing government agenda to lead the way in making passive housing part of the mainstream?

Related articles

-

Worlds apart

Frank Gaffikin

We are at an inflexion point as a species with an increasing need for collaborative responses to the global crises we face.

-

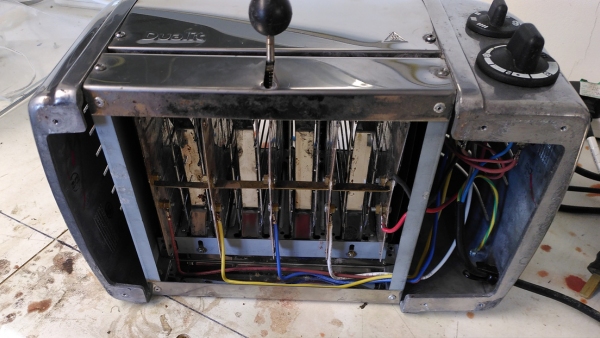

Why aren't consumer durables durable?

Moray MacPhail

A tale of two toasters demonstrates the trade-offs that need to be considered when we're thinking about the long-term costs of how and what we consume.

-

You talked, we listened

Mike Thatcher

The RSA responds to feedback on the Journal from over 2,000 Fellows who completed a recent reader survey.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

I was extremely pleased to treasure this enter regarding Behavior on quiet shelter. I wanted to acknowledge you for this monumental scan!! I definitely enjoyed each microscopic scrap of it further I get you bookmarked to hinder absent the unfamiliar pad you courier.

It seems that most passive housing designs have walls of glass (for obvious reasons) - I think that will have to be considered in areas where people culturally are more private. When I have seen them in other countries, homeowners don't even have curtains. I can't imagine living in a place like that. If you cover the glass with drapes, does the system still work as well? How about in places where cooling is more of the concern and not heating? I also have a concern about solar panels, the chemicals used to produce them are extremely toxic, so that while you are doing something good for the environment on one hand, you are damaging it with the other. Also, they are cost prohibitive, in that they have a life expectancy of about 10 years, which is about the same time it takes you to make the money back in savings from their installation.

I do think passive housing is to be explored but it is not the master solution.